There’s a kind of sucker punch in many presentations of American history, wherein we are told that the Puritans left England for America because they had suffered religious persecution—and then the Puritans persecuted other religions here! We’re given the impression that they were looking for freedom of religion and then denied it to others.

In the 1650’s several of our ancestors became Quakers and enduried escalating fines, prison, banishment, whipping and ear cutting. Some of these ancestors were closely involved when four Quakers were condemned to death and executed by public hanging for their religious beliefs in Boston in 1659, 1660 and 1661. Richard SCOTT’s daughter Patience, in June, 1659, a girl of about eleven years, having gone to Boston as a witness against ‘the persecution of the Quakers, was sent to prison; others older being banished. Today we ask, “What kind of people put an 11 year old girl in jail? ”

In our 2011 imagination, the Quakers are the conscientious objector good guys while the Puritans are the hypocritical tyrants. Almost any book you read about the Massachusetts Bay Colony gives you the feeling that the moment those people set foot on shore in America they started betraying their own values. Objectivity is hard to come by when you’re reading about the Puritans. Is our modern perspective accurate?

Navigate this Report

1. Puritan Perspective

2. Quaker Perspective

3. Trials & Tribulations

4. Boston Martyrs

5. Aftermath

In 1649, John Endicott succeeded John Winthrop as Governor in and he was far more intolerant of religious dissention. He feared that if he permitted the Quakers to express their views in Massachusetts Bay Colony, the whole structure of the Church-State partnership might collapse.

Jul 1656 – Two Quaker missionaries, Anne Austin and Mary Fisher landed in Boston to bring the message of the “inner light” to the New World and immediatley became targets of the civil government. These two members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) left England, where Fisher had suffered beatings because of her beliefs, and sailed to Barbados. After apparently finding success in Barbados, the two missionary women set sail in July 1656 aboard the Swallow. They landed in Boston and immediately became targets of the civil government. Deputy-governor Richard Bellingham, in charge during the absence of Governor William Endicott, ordered the women confined to the ship. Their books and belongings were taken and searched. News of the heretical views of the Quakers had preceded these women across the Atlantic. Ann and Mary had brought approximately 100 books or writings with them, and these were burnt, and the pair cast into prison. Fines were levied against anyone speaking to them, and the women were stripped and searched for any evidence of witchcraft, and their prison window was boarded up so that no one could see them.

One man, Nicholas Upsall, came to their rescue, and paid the fine either to be permitted to speak with them and/or provide them with food. The women were kept confined in this manner for five weeks, then shipped back to Barbados. Governor Endicott is reported to have stated that he would have had the women beaten. Fear of the Quaker “heresy” was indeed great. Ann Austin and Mary Fisher were persecuted before there were any laws enacted against the Friends in America

On August 9, 1656, the port authorities were alerted to search the Speedwell as it entered Boston Harbor before anyone landed. The passenger list had “Q’s” beside the names of four men and four women, and Endicott ordered these eight brought directly to Boston court. Christopher Holder (later to marry Richard SCOTT’s daughter Mary) and John Copeland led the group and they dumbfounded Endicott and the local ministers with their familiarity with the Bible. More irritating to Endicott was Christopher Holder’s knowledge of the law. When they were marched off to jail, Holder and Copeland made immediate demands for their release, stating that there was no law that justified their imprisonment.

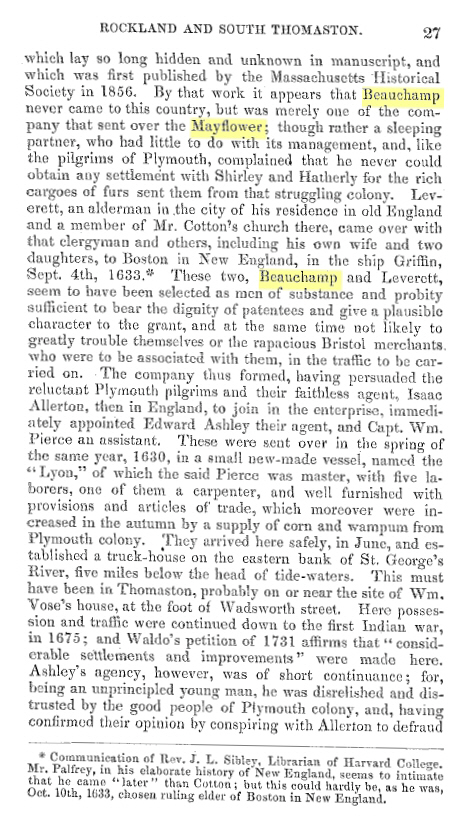

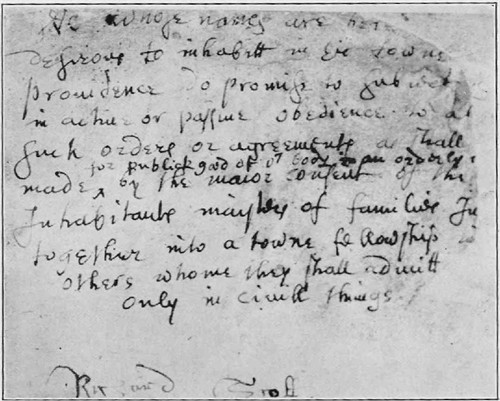

Governor Endicott knew this was true. There was nothing in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Charter which permitted the imprisonment of anyone merely on grounds of their religious beliefs, and so he devised a tactic to get rid of the Quakers. The Massachusetts General Court met in mid-October of 1656 and 1657 and succeeded in passing several laws against “the cursed sect of heretics … commonly called Quakers” which permitted banishing, whipping, and using corporal punishment (cutting off ears, boring holes in tongues). On October 14, 1656 the Court ordered:

That what master or commander of any ship, barke, pinnace, catch, or any other vessel that shall henceforth bring into any harbor, creeks, or cove without jurisdiction any known Quaker or Quakers, or any other blasphemous heretics shall pay … the fine of 100 pounds … [and] they must be brought back from where they came or go to prison.

After trying to cover all the loopholes in any possible entry to Boston, the Court addressed what it would do with anyone who persisted successfully. It was decided that such a person should go to the House of Correction and be severly whipped, kept constantly at work, and not allowed to speak to anyone. They set up certain fines: 54 pounds for having any Quaker books or writing “concerning their devilish opinions,” 40 pounds for defending any Quaker of their books, 44 pounds for a second offence, and the “House of Corection for a third offence … until there be a convenient passage for them to be sent out of this land.” These laws were read on the street corners of Boston with the beat of drums for emphasis.

Christopher Holder and John Copeland sat in their cells where they could hear the rattling of the drums and realized they were going to have to leave on the next available ship departing for England. After eleven weeks Holder, Copeland and the other six Quakers of the Speedwell were deported to England, but they immediately took steps to return.

In October 1656 Massachusetts Bay Colony established the following law:

“Whereas there is a cursed sect of heretics lately risen up in the world, which are commonly called Quakers…” upon entering within a jurisdiction, “shall be forthwith committed to the house of correction, and at their entrance to be severely whipped, and by the master thereof be kept constantly to work, and none suffered to speak with them…” and it is ordered “that what person or persons soever shall revile the office or person of the magistrates or ministers, as is usual with Quakers, such person or persons shall be severely whipped, or pay the sum of five pounds.”

Mary Dyer’s return to New England in 1657 was ill-timed. Upon her return to America from England, unaware of the new laws, Mary Dyer, accompanied by Ann Burden, made a stop-over in the Massachusetts Bay Colony on her journey home to Rhode Island so that Ms Burden could settle the estate of her deceased husband in Boston. Mary Dyer and Ann Burden were arrested almost immediately upon setting foot on Massachusetts soil as undesired missionaries of the outlawed religion. Despite their protests, they were kept in jail incommunicado in darkened cells with boarded up windows. Mary’s books and Quaker papers were confiscated and burned. Mary finally was able to slip a letter out through a crack to someone outside the jail, but it took a long time to reach William Dyer in Newport.

Two and a half months later, Governor Endicott was startled when William Dyer barged into his home, demanding that his wife should be freed immediately. While Endicott knew that William had been disenfranchised by Boston, he was still highly respected by the Boston authorities for his prominent position in Rhode Island. They would have to free Mary Dyer because of William’s prestige, but only on a condition. William was put under a heavy bond and made to “give his honor” that if his wife was allowed to return home, he was “not to lodge her in any town of the colony nor to permit any to have speech with her on the journey.” Under no condition should Mary ever return to Massachusetts.

Back in Rhode Island, Mary became a prominent Quaker minister, traveling over the new country. Preaching “inner light,” Mary rejected oaths of any kind, taught that sex was no determinant for gifts of prophecy, and contended that women and men stood on equal ground in church worship and organization. In 1658 she was expelled from New Haven for preaching.

At the end of 1658 the Massachusetts legislature, by a bare majority, enacted a law that every member of the sect of Quakers who was not an inhabitant of the colony but was found within its jurisdiction should be apprehended without warrant by any constable and imprisoned, and on conviction as a Quaker, should be banished upon pain of death, and that every inhabitant of the colony convicted of being a Quaker should be imprisoned for a month, and if obstinate in opinion should be banished on pain of death. Some Friends were arrested and expelled under this law.

Meanwhile, Christopher Holder and the seven other banished Quakers had returned to England. Christopher wasted no time in getting in touch with George Fox, in order to secure a ship for a return trip to New England. While Mary was being rebuked in New Haven, Christopher Holder and John Copeland were being ordered to leave Martha’s Vineyard. Hiding in the sand dunes for several days, they met up with friendly Indians who volunteered to help them cross over to Massachusetts.

They landed in Sandwich where they found a community of people unsettled in their religious affiliations and had who had just lost their minister. Holder and Copeland were received with enthusiasm by about eighteen families who were ready to become Quakers. Many of these families were our ancestors and their relatives. You can see their stories in my post Puritans V. Quakers – Trials and Tribulations.

Finding a beautiful dell by a quiet stream in the woods, they called their enchanted hideaway “Christopher’s Hollow,” a name which has remained with the place. (See Google Maps Christopher Hollow Road). A circle of Friends gathered together and sat on a circle of stones to share their religious convictions. It was the first real Friends meeting in America, and the start of regular meetings.

Happy with this success, Holder and Copeland moved from Sandwich to Duxbury, from town to town in Massachusetts, leaving fifteen converted Quaker “ministers” in their wake. Eventually, Governor Endicott got wind of their activities and alerted scouts throughout New England to arrest them, but they remained free until they walked into Salem, Endicott’s home town.

When Holder arrived at the Salem Congregational Church, he listened to the sermon of the day, then arose from the rear of the church to challenge what had been said and present Quaker alternatives. One of Endicott’s men seized Holder, hurled him bodily to the floor of the church and stuffed a leather glove and handkerchief down his throat. Holder turned blue, gagged, and gasped for life. He was close to death when Samuel Shattuck, a member of the congregation, pushed Endicott’s man aside and retrieved the glove and handkerchief from Holder’s throat and worked hard to resuscitate him. A lifelong friendship between Shattuck and Holder started at that moment.

Preceding Ms. Dyer’s and Ms Burden’s arrest by two days, Holder, Copeland and Shattuck were all taken to Boston prison. Starved, beaten and whipped, the three men spent the next two and half months in jail. Shattuck was freed by paying a 20 shilling bond. Holder and Copeland were brought before Endicott who ordered that each should have thirty lashes. After several months, they were released from prison, but were soon to return.

Also jailed were Holder and Copeland’s host, Salem church members, Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick . Though Lawrence was released, his wife remained imprisoned for seven weeks for having in her possession a paper written by their guests.

Shortly after their release from jail, Christopher Holder and John Copeland first went to Martha’s Vineyard but was turned away by Thomas Mayhew, and then on August 20, 1657, arrived in Sandwich where they were welcomed by many families. On April 15, 1658, Endicott’s spies arrested them in the middle of a meeting and marched them to Barnstable where they were stripped and bound to the post of an outhouse. With the standard three-corded rope, they were each given 33 lashes until the bodies ran with blood. The Friends of Sandwich stood in horr as “ear and eye witnessses” to the cruelty.”

After recovering from the scourging, Holder and Copeland returned again to Boston on June 3, 1658 where they were once again arrested. On September 16, 1658 by the order of Governor Endicott, Christopher Holder, a future son-in-law of Richard SCOTT, had his right ear cut off by the hangman at Boston for the crime of being a Quaker. Richard’s wife, Katherine MARBURY SCOTT (Anne Hutchinson ‘s sister), was present, and remonstrating against this barbarity, was thrown into prison for two months, and then publicly flogged ten stripes with a three-corded whip. Mrs. Scott protested

“that it was evident they were going to act the work of darkness or else they would have brought them forth publicly and have declared them offences, that all may hear and fear.”

For this utterance the Puritan Fathers of Boston

“committed her to prison and they gave her ten cruel stripes with a three-fold corded knotted whip” shortly after “though ye confessed when ye had her before you that for ought ye knew she had been of unblamable character and though some of you knew her father and called him Mr. Marbury and that she had been well bred (as among men and had so lived) and that she was the mother of many children. Yet ye whipped her for all that, and moreover told her that ye were likely to have a law to hang her if she came thither again.”

To which she answered:

“If God calls us, woe be unto us if we come not, and I question not but he whom we love will make us not to count our lives dear unto ourselves for the sake of his name.”

To which vow, Governor icott, replied:

“And we shall be as ready to take any of your lives as ye shall be to lay them down.”

On October 19, 1658, the Massachusetts authorities during a stormy session had passed by a single vote a law banishing Quakers under pain of death.

June 1659 – Two Friends, William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson, felt called to go to Massachusetts, although a new law imposed the death penalty on Friends. Richard SCOTT’s daughter, Patience , only eleven years old at the time, went to Boston as a witness againt the persecution of the Quakers, and was sent to prison; others older being banished.

“and some of ye confest ye had many children and that they had been well educated and it were well if they could say half as much for God as she could for the Devil.”

This prompted Mary Dyer to return and protest their treatment. For this action, she was put back in jail. Dyer was released after her husband wrote a letter to Endicott.

William Dyer wrote a letter to the Massachusetts authorities, dated August 30, 1659, chastising the magistrates for imprisoning his wife without evidence or legal right. “You have done more in persecution in one year than the worst bishops did in seven, and now to add more towards a tender woman,” wrote William, “… that gave you no just cause against her for did she come to your meeting to disturb them as you call itt, or did she come to reprehend the magistrates? [She] only came to visit her friends in prison and when dispatching that her intent of returning to her family as she declared in her [statement] the next day to the Governor, therefore it is you that disturbed her, else why was she not let alone.” (Click here to read full text of William’s letter.)

On Sep 12 1659, the Quakers were released from prison and banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony under threat of execution should they return. Nicholas Davis and Mary Dyer obeyed, but Robinson and Stephenson felt it their duty to remain and continue their ministry, deteremined to “look [the] bloody laws in the face.” Within a month they were again arrested. When it was learned Christopher Holder was again in jail and threatened with further torture, Mary Dyer, Hope Clifton and Mary Scott (future wife of Christopher Holder and Anne Hutchinson’s niece) walked through the forest to Boston from Providence to plead for his release and that of others. Mary Dyer was arrested while speaking to Holder through the prison bars.

There was no mistaking the moves of Holder, Robinson, Stephenson and Mary Dyer. They deliberately challenged the legal right of Endicott to carry out the death penalty. Doing what their compatriots were doing in England, they returned to the field as soon as they were released, willing to lay down their lives, if necessary, yet never striking a blow in retaliation. Passive non-resistance and religious appeals constituted the ammunition and weapons of this Colonial Quaker army. They had all been banished with the assurance that if they returned death awaited them.

On Oct 19 1659 Mary Dyer was brought before the General Court with Robinson and Stephenson. Asked why they had returned in defiance of the law, they replied that “the ground and cause of their coming was of the Lord.” When Gov. John Endicott pronounced sentence of death, Mary Dyer replied, “The will of the Lord be done.” “Take her away, Marshal,” commanded Endicott. “Yea and joyfully I go,” responded Mary Dyer.

That week in jail, Mary, William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson sat in their cells writing pleas to the General Court to change the laws of banishment upon pain of death. (Click here to read the full text of Mary’s letter.)

On October 27, the three Quakers were led through the streets to the gallows with drums beating to prevent them from addressing the people. Robinson and Stephenson were hanged, but Mary Dyer, her arms and legs bound and the noose around her neck, received a prearranged last-minute reprieve as a result of intercession of Gov. John Winthrop, Jr. of Connecticut, Gov. Thomas Temple of Nova Scotia and her son.

Mary Dyer, her arms and legs bound and the noose around her neck, received a prearranged last-minute reprieve as a result of intercession of Gov. John Winthrop, Jr. of Connecticut, Gov. Thomas Temple of Nova Scotia and her son.

Back in her cell, Mary composed another letter to the General Court, from which comes the inscription on her statue at Boston: “Once more the General Court, Assembled in Boston, speaks Mary Dyar, even as before: My life is not accepted, neither availeth me, in Comparison of the Lives and Liberty of the Truth and Servants of the Living God, for which in the Bowels of Love and Meekness I sought you; yet nevertheless, with wicked Hands have you put two of them to Death, which makes me to feel, that the Mercies of the Wicked is Cruelty.” (Click here to read this second letter in its entirety.)

On October 18, 1659, William Dyer, Jr.’s petition on behalf of his mother to Mass. authorities, was thus answered: “Whereas Mary Dyer is condemned by the General Court to be executed for her offence; on the petition of William Dyer, her son, it is ordered the said Mary Dyer shall have liberty for forty-eight hours after this day to depart out of this jurisdiction, after which time being found therein she is to be executed.”

Mary returned unwillingly back to Rhode Island. She was accompanied by four horsemen who followed her fifteen miles south of Boston. From there she was left in the custody of one man to escort her back to Rhode Island.

Once home, Mary longed for the companionship of other Quakers. She busied herself across Long Island Sound on Shelter Island where a group of Indians had approached her, asking if she would hold Quaker meetings with them. Although Mary was out of danger in this environment, she was not content. She made it known that she must return to Boston to “desire the repeal of that wicked law against God’s people and offer up her life there.” In late April, 1660, in obedience to her conscience and in defiance of the law and without telling her husband, she returned once more to Boston.

It took a week for the news to reach William Dyer that Mary had left Shelter Island. Quickly, he wrote again to the magistrates of Boston. (Click here to read William’s moving letter.) Governor Endicott received the letter and presented it to the General Court. Too bad if William was having trouble with his wife. She was giving them trouble, too. She had no right to come back and defy their orders. The General Court summoned Mary before them on May 31, 1660.

“Are you the same Mary Dyer that was here before?” Governor Endicott asked her.”I am the same Mary Dyer that was here at the last General Court,” she replied.

“You will own yourself a Quaker, will you not?”

“I am myself to be reproachfully called so,” Mary said stiffly.

Governor Endicott said, “The sentence was passed upon you by the General Court and now likewise; you must return to the prison and there remain until tomorrow at nine o’clock; then from thence you must go to the gallows, and there be hanged till you are dead.”

Mary Dyer did not flinch. “This is no more than what you said before.”

“But now it is to be executed,” said Endicott. “Therefore prepare yourself tomorrow at nine o’clock.”

“I came in obedience to the will of God to the last General Court desiring you to appeal your unrighteous laws of banishment on pain of death,” said Mary, “and that same is my work now, and earnest request, although I told you that if you refused to repeal them, the Lord would send others of his servants to witness against them.”

“Are you a prophetess?” asked the Governor.

“I speak the words that the Lord speaks in me and now the thing has come to pass.”

Endicott reached his saturation point and, waving to a prison guard, yelled, “Away with her! Away with her!”

At the appointed time on June 1, 1660, Mary was escorted from her prison cell by a band of soldiers to the gallows a mile away. Apprehensive that a gathering crowd might become uncontrollably compassionate, the Magistrates took every precaution to cut off communication between Mary Dyer and her followers. Led through the streets sandwiched between drummers, with a constant rat-a-tat-tat in front and behind her, Mary Dyer walked to her death.

When Mary Dyer returned to Boston, protesting the harsh laws against the Quakers, she was arrested again. Once more, she was sentenced to hang.

Despite these precautions, some of the followers were able to get close enough to appeal to her to acquiesce in banishment. “Mary Dyer, don’t die. Go back to Rhode Island where you might save your life. We beg of you, go back!” “Nay, I cannot go back to Rhode Island, for in obedience to the will of the Lord I came,” Mary said, “and in His will I abide faithful to the death.”

At the place of execution the drums were quieted and Captain John Webb spoke, trying to justify what was about to happen. “She has been here before and had the sentence of banishment upon pain of death and has broken the law in coming again now,” he said. “It is therefore SHE who is guilty of her own blood.”

Mary contradicted him. “Nay, I came to keep bloodguiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust laws of banishment upon pain of death made against the innocent servants of the Lord. Therefore, my blood will be required at your hands who wilfully do it.” Mary then turned towards the crowd and continued, “But, for those who do it in the simplicity of their hearts, I desire the Lord to forgive them. I came to do the will of my father, and in obedience to this will I stand even to death.”

Pastor Wilson cried, “Mary Dyer, O repent, O repent, and be not so delued and carried away by the deceit of the devil.” Mary looked directly at him and said, “Nay, man, I am not now to repent.”

John Norton stepped forward and asked, “Would you have the elders pray for you?” Mary responded, “I desire the prayer of all the people of God.” A voice from the crowd called out, “It may be that she thinks there is none here.” John Norton pleaded, “Are you sure you dont’ want one of the elders to pray for you?” Mary answered, “Nah, first a child, then a young man, then a strong man, before an elder in Christ Jesus.”

Someone from the crowd called out, “Did you say you have been in Paradise?” Mary answered, “Yea, I have been in Paradise several days and now I am about to enter eternal happiness.”

Captain John Webb signalled to [our ancestor] Edward WANTON (1632 – 1716),, officer of the gallows, who adjusted the noose. He was “so affected at the sight” of Mary’s courageous sacrifice “he became a convert to the cause of the Friends ” He was a prominent Boston shipbuilder who converted to Quakerism and moved to Scituate, Massachusetts in 1661. The Wanton family was among the most prominent families of colonial Rhode Island, Two of his sons, one nephew and one grandson become Governors of Rhode Island and were known as the “Fighting Quakers.” Three years later Wanton was arrested in Boston for holding a Quaker meeting in his home.

Mary needed no assistance in mounting the scaffold and a small smile lighted her face. Pastor Wilson had his large handkerchief ready to place over her head so no one would have to see that look of rapture twisted to distortion – only the dangling body. As her neck snapped, the crowd stood paralyzed in the silence of death until a spring breeze lifted her limp skirt and set it to billowing. “She hangs there as a flag for others to take example by,” remarked an unsympathetic bystander. That was indeed Mary Dyer’s intention – to be an example, a “witness” in the Quaker sense, for freedom of conscience.

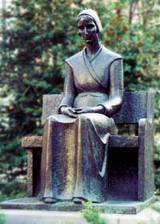

Despite all the frantic attempts of the Boston magistrates to rid themselves of the challenging Quakers, they failed. Mary’s death came gradually to be considered a martyrdom even in Massachusetts, where it hastened the easing of anti-Quaker statutes. In 1959 by authority of the Massachusetts General Court, which had condemned her nearly 300 years before, a bronze statue was erected in her memory on the grounds of the State House in Boston. A statue of her friend, Anne Hutchinson, stands in front at the other wing. The words of Mary Barrett Dyer, written from her cell of the Boston jail are engraved beneath:

My Life not Availeth Me

In Comparison to the

Liberty of the Truth’

William Leddra

William’s home was in Barbados, but he is said to have been by birth a Cornishman; and his occupation, it appears, was that of a clothier. We find him engaged very early in visiting the West Indies as a minister, and in 1657 he proceeded in that character to New England.

Reaching Salem [in July 1658], William Brend and William Leddra were warmly welcomed by the few faithful Friends of that place, with whom they were favored to hold several meetings to their mutual refreshment and comfort.

On First-day, the 20th of Fourth Month, they attended one held at the house of Nicholas Phelps, in the woods, about five miles from Salem. A magistrate of the town hearing of the intended meeting, came with a constable, for the purpose of breaking it up, and securing the two strangers; but failing in his purpose, he left the company, with a threat that he would prosecute the Friends who were present. From Salem the two gospel messengers traveled to Newburyport, where also they had some religious service. Their passing thus from place to place, in the very heart of the Puritan population of New England, and by their powerful ministry making converts to the doctrines they professed, aroused the fears of the local magistracy to this new state of things.

After leaving Newburyport, they were soon overtaken by a zealous ruler of the place, who arrested them and carried them to Salem. The court, which was then sitting in the town, had the Friends brought up for examination. Here they were interrogated respecting the doctrines they were promulgating, but their answers were so clear and convincing, and they appealed so effectually to the consciences of the magistrates, that the latter confessed they discovered nothing heretical or dangerous in their opinions.

The court, however, told the prisoners that they had a law against Quakers, and that law must be obeyed. An order for their committal immediately followed, and in a few days they were removed to Boston prison. Six Friends of Salem were also committed for having attended the meeting at the house of Nicholas Phelps.

William Brend and William Leddra, who were deemed special offenders, were separated from their companions. They were placed in a miserable cell, the window of which was so stopped, as not only to deprive them of light, but also of ventilation, while all conversation between them and the citizens was strictly forbidden. The jailer, following the cruel course which he had pursued towards Thomas Harris, refused to allow them an opportunity of purchasing food, though they offered to pay for it. But he told them, it was not their money, but their labor he desired. Thus he kept them five days without food, and then with a three-corded whip gave them twenty blows. An hour after he told them, they might go out, if they would pay the marshal that was to lead them out of the country. They judging it very unreasonable to pay money for being banished, refused this, but yet said, that if the prison-door was set open, they would go away.

The next day the jailer came to W. Brend, a man in years, and put him in irons, neck and heels so close together, that there was no more room left between each, than for the lock that fastened them. Thus he kept them from five in the morning, till after nine at night, being the space of sixteen hours. The next morning he brought him to the mill to work, but Brend refusing, the jailer took a pitched rope about an inch thick, and gave him twenty blows over his back and arms, with as much force as he could, so that the rope untwisted; and then, going away, he came again with another rope, that was thicker and stronger, and told Brend, that he would cause him to bow to the law of the country, and make him work. Brend judged this not only unreasonable in the highest degree, since he had committed no evil, but he was also altogether unable to work for he lacked strength for want of food, having been kept five days without eating, and whipped also, and now thus unmercifully beaten with a rope. But this inhuman jailer relented not, but began to beat anew with his pitched rope on this bruised body, and foaming at his mouth like a madman, with violence laid ninety-seven more blows on him, as other prisoners that beheld it with compassion, have told ; and if his strength, and his rope had not failed him, he would have laid on more; he threatened also to give him the next morning as many blows more. But a higher power, who sets limits even to the raging sea, and has said, “to here you shall come, but no further,” also limited this butcherly fellow; who was yet impudently stout enough to say his morning prayer. To what a most terrible condition these blows brought the body of Brend, who because of the great heat of the weather, had nothing but a serge cassock upon his shirt, may easily be conceived. His back and arms were bruised and black, and the blood hanging as in bags under his arms; and so into one was his flesh beaten, that the sign of a particular blow could not be seen; for all was become as a jelly. His body being thus cruelly tortured, he lay down upon the boards, so extremely weakened, that the natural parts decaying, and strength quite failing, his body turned cold. There seemed as it were a struggle between life and death; his senses were stopped, and he had for some time neither seeing, feeling, nor hearing; till at length a divine power prevailing, life broke through death, and the breath of the Lord was breathed into his nostrils.

Now, the noise of this cruelty spread among the people in the town, and caused such a cry, that the governor sent his surgeon to the prison to see what might be done; but the surgeon found the body of Brend in such a deplorable condition, that, as one without hopes, he said, his flesh would rot from off his bones, before the bruised parts could be brought to digest. This so exasperated the people, that the magistrates, to prevent a tumult, set up a paper on their meeting-house door, and up and down the streets, as it were to show their dislike of this abominable, and most barbarous cruelty; and said, the jailer should be dealt withal the next court.

But this paper was soon taken down again upon the instigation of the high priest, John Norton, who, having from the beginning been a fierce promoter of the persecution, now did not hesitate to say, “W. Brend endeavored to beat our gospel ordinances black and blue, if he then be beaten black and blue, it is but just upon him; and I will appear in his behalf that did so.” It is therefore not much to be wondered at, that these precise and bigoted magistrates, who would be looked upon to be eminent for piety, were so cruel in persecuting, since their chief teacher thus wickedly encouraged them to it.

24 Mar 1661 – After several other arrests and jailings, William Leddra stood at the foot of the tree where he was to be hanged. As his arms were being tied he said, “For bearing my testimony for the Lord against deceivers and the deceived, I am brought here to suffer.” His final words were, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.”

A few moments later, he became the last Quaker to swing in Boston for the crime of returning from banishment. Even the court acknowledged that it “found nothing evil” in William. Even so, he had suffered beatings and banishment for preaching in Massachusetts. When he dared to return in 1660, Puritan authorities arrested him. The charges against him were typical. He had sympathized with the Quakers who were executed before him; he had refused to remove his hat, and he used the words “thee” and “thou,” which, to Quakers, implied the equality of all people. William lay in prison all that winter without heat. But on the last day of his life, chained to a log in a dark cell, he wrote to his wife:

“Most Dear and Inwardly Beloved, “The sweet influences of the Morning Star, like a flood distilling into my innocent habitation, hath filled me with the joy of [God] in the beauty of holiness, that my spirit is, as if it did not inhabit a tabernacle of clay. Oh! My Beloved, I have waited as a dove at the windows of the ark, and I have stood still in that watch, wherein my heart did rejoice, that I might in the love and life speak a few words to you sealed with the Spirit of Promise, that the taste thereof might be a savor of life to your life, and a testimony in you, of my innocent death.”

Edmund PERRY’s son-in-law Robert Harper, a prominent Quaker in Boston caught Leddra’s body under the scaffold when the hangman cut it down. For this sign of respect toward his dead friend, Robert and his wife, were banished. Our Quaker ancestors were also hounded in the courts.

Sources:

http://www.hallvworthington.com/Leddra.html

http://massmoments.org/moment.cfm?mid=347

http://www.awesomestories.com/famous-trials/mary-dyer/mary-dyer-becomes-a-quaker

In November, 1637, William was disenfranchised and disarmed along with dozens of other followers of Anne Hutchinson. On March 22, 1638, when Anne Hutchinson was excommunicated from the church and withdrew from the assemblage, Mary Dyer rose and accompanied her out of the church. As the two women left, there were several women hanging around outside the church and one was heard to ask, “Who is that woman accompanying Anne Hutchinson?” Another voice answered loud enough to be heard inside the church, “She is the mother of a monster!”

In November, 1637, William was disenfranchised and disarmed along with dozens of other followers of Anne Hutchinson. On March 22, 1638, when Anne Hutchinson was excommunicated from the church and withdrew from the assemblage, Mary Dyer rose and accompanied her out of the church. As the two women left, there were several women hanging around outside the church and one was heard to ask, “Who is that woman accompanying Anne Hutchinson?” Another voice answered loud enough to be heard inside the church, “She is the mother of a monster!”