The Great Swamp Fight on December 19, 1675 was the most significant battle of King Philip’s War, what has been called the bloodiest (per capita) conflict in the history of America. It was a critical blow to the Narragansett tribe from which they never fully recovered. In April 1676, the Narragansett were completely defeated when the Wampanoag sachem Metacom was shot in the heart by John Alderman, a Native American soldier. The Narragansett tribe was not recognized by the Federal Government until 1983 and today includes 2,400 members.

As I worked out our family genealogy, the Great Swamp Fight kept appearing again and again. Our family seems to have an especially intimate relationship with this battle, but I’m beginning to think that every family was equally involved. Nine direct ancestors participated, four were officers and one was killed. 27 close relatives were part of the fight of whom 6 were officers, six were killed or died of their wounds and six were wounded and survived. Of the three small regiments involved, eleven officers were our ancestors or their children.

Navigate this Report

1. Overview

2. Background

3. The Battle

4. General Staff

5. Massachusetts Regiment

6. Plymouth Regiment

7. Connecticut Regiment

8. Joshua Tefft – the Only American Drawn & Quartered

King Philip’s War was an armed conflict between Native American inhabitants of present-day southern New England and English colonists and their Native American allies in 1675–76. The war is named after the main leader of the Native American side, Metacomet, known to the English as “King Philip”.

King Phillip by Paul Revere - Illustration from the 1772 edition of Benjamin Church's The Entertaining History of King Philip's War

The war was the single greatest calamity to occur in seventeenth-century Puritan New England. In little over a year, nearly half of the region’s towns were destroyed, its economy was all but ruined, and much of its population was killed, including one-tenth of all men available for military service. Proportionately, it was one of the bloodiest and costliest wars in the history of North America. More than half of New England’s ninety towns were assaulted by Native American warriors.

Great Swamp Fight Compared to Today’s Population

|

1675 |

Today’s U.S. Equivalent (11-22-2011) |

|

| Population |

52,000 |

312,648,000 |

| Killed Great Swamp Fight |

70 |

420,900 |

| Wounded Great Swamp Fight (Many later died) |

150 |

901,900 |

| Colonists Killed and Wounded |

220 |

1,322,700 |

| Naragansett Warriors Killed |

30 to 40 |

180,400 – 240,500 |

| Naragansett Old Men, Women, Children Killed |

300 |

1,803,700 |

The Great Swamp Fight Monument is in the woods three or four miles from the University of Rhode Island Campus (Google Maps Satellite View)

The Great Swamp Fight Obelisk - In 1906 a rough granite shaft about 20 feet high was erected by the Rhode Island Society of Colonial Wars to commemorate this battle. Around the mound on which the shaft stands are four roughly squared granite markers engraved with the names of the colonies which took part in the encounter and two tablets on opposite sides of the shaft give additional data.

In 1636, the Narragansett sachems (leaders), Canonicus and Miantonomi sold the land that became Providence to Roger Williams. During the Pequot War, the Narragansett were allied with the New England colonists. However, the brutality of the English shocked the Narragansetts, who returned home in disgust. After the defeat of the Pequot, the Narrangansett had conflict with the Mohegans over control of the conquered Pequot land.

In 1643 the Narragansett under Miantonomi invaded what is now eastern Connecticut. The plan was to subdue the Mohegan nation and its leader Uncas. Miantonomi had between 900-1000 men under his command. The invasion turned into a fiasco, and Miantonomi was captured and executed by Uncas’ brother. The following year, the new war leader Pessicus of the Narragansett renewed the war with the Mohegan. With each success, the number of Narragansett allies grew. The Mohegan were on the verge of defeat when the English came and saved them. The English sent troops to defend the Mohegan fort at Shantok. When the English threatened to invade Narragansett territory, Canonicus and his son Mixanno signed a peace treaty. The peace would last for the next 30 years, but the encroachment by the growing colonial population gradually began to erode any accords between natives and settlers.

In King Philip’s War, the Native Americans wanted to expel the English from New England. They waged successful attacks on settlements in Massachusetts and Connecticut, but Rhode Island was spared at the beginning as the Narragansett remained officially neutral.

The United Colonies of New England declared war against the Narragansett Indians on November 2, 1675, charging them, among other things, with “relieving and succouring Wampanoag women and children and wounded men” and not delivering them to the English, and also because they “did in a very reproachful and blasphemous manner, triumph and rejoice” over the English defeat at Hadley. They voted to raise a thousand soldiers to be sent against the Narragansetts unless their sachems gave up the fugitive Wampanoags.

On 2 Nov 1675, General Josiah Winslow led a combined force of over 1000 colonial militia including about 150 Pequot and Mohegan Indians against the Narragansett tribe living around Narragansett Bay.

Several abandoned Narragansett Indian villages were found and burned as the militia marched through the cold winter around Narragansett Bay. The forces of the United Colonies under Governor Winslow marched across Rhode Island and on December 14 attacked the village of the Squaw Sachem Matantuck near Wickford and burned 150 wigwams, killing seven Indians and taking nine prisoners. The Narragansetts then began a guerrilla warfare, sniping Colonial troops wherever occasion offered. The tribe had retreated to a large fort in the center of a swamp near Kingston, Rhode Island.

A fort in the Great Swamp had been built by the Narragansett Sachem, Canonchet, as a place of refuge. Because of its location on a small island of dry land in the midst of a great swamp, he no doubt considered it impregnable. The massive fort occupied about 5 acres of land. It was, however, only partially completed and consisted of “pallisadoes stuck upright in a hedge of about a rod in thickness.” Two fallen trees formed natural bridges which were the only entrances and the principal one was guarded by a block house. Inside the fort the stores, harvests and accumulated wealth of the Narragansetts had been brought and there asylum had been offered the aged and infirm and the women and children of the Wampanoags of King Philip.

The building of such a defensive structure gives credence to the argument that the Narragansett never intended aggressive actions, thus the colonist’s preemptive attack may have been unwarranted and overzealous.

On the night of December 15 the Indians surrounded Jireh Bull’s large stone house on Tower Hill and massacred all but two of the occupants. The smoldering ruins of the house were found by English scouts the next day. It is possible that the Indians had learned of a plan for the Connecticut contingent to join the other forces at this house and had destroyed it in order to handicap the colonies. Three days later the two English forces joined at Pettaquamscutt and planned to attack the Indians the next day.

Ordinarily the swamp was practically impenetrable, as it is to this day, but due to the severe December weather the marshy ground had frozen and the English soldiers gained easy access to the island. The Indian outposts retreated into the fort where they were followed by the English. The terrible battle which then began took place amidst ice, snow, under brush and fallen trees.

It had been at 5 AM that the white soldiers had formed up after their night in the cold snow without blankets, and set out toward this Narragansett stronghold. They had arrived at the edge of the Great Swamp, an area around , at about 1 PM. The Massachusetts troops in the lead were fired upon by a small band of native Americans and pursued without waiting for orders. As the natives retreated they came along across the frozen swamp to the entrance of the fort, which was on an island of sorts standing above the swamp, and consisted of a triple palisade of logs twelve feet high. There were small blockhouses at intervals above this palisade. Inside, the main village sheltered about 3,000 men, women, and children.

The Massachusetts troops had been enticed to arrive at precisely the strongest section of the palisade where, however, there was a gap for which no gate had yet been built. Across this gap the natives had placed a tree trunk breast height, as a barrier to check any charge, and just above the gap was a blockhouse. Without waiting for the Plymouth and Connecticut companies, the Massachusetts soldiers charged the opening and swarmed over the barrier. Of the Massachusetts troops Capts. Mosely and Davenport led the van and came first upon the Indians, and immediately opened fire upon them, Five company commanders were killed in the charge but the troops managed to remain for a period inside the fort before falling back into the swamp.

The Massachusetts men, now joined by Plymouth, gathered themselves for a second charge. Meanwhile, Major Treat led his Connecticut troops round to the back of the fort where the palisade had not been finished. Here and there the posts were spaced apart and protected only by a tangled mass of limbs and brush. The men charged up a bank under heavy fire and forced their way past the palisade. As they gained a foothold inside, the second charge at the gap also forced an entrance and the battle raged through the Indian village.

It was a fight without quarter on either side, and was still raging at sunset when Winslow ordered the wooden lodges put to the torch. The flames, whipped by the winds of the driving snowstorm, spread quickly, burning 600 wigwams in the crowded fort. The “shrieks and cries of the women and children, the yelling of the warriors, exhibited a most horrible and appalling scene, so that it greatly moved some of the soldiers. They were in much doubt and they afterwards seriously inquired whether burning their enemies alive could be consistent with humanity and the benevolent principle of the gospel,” says one early account.

Winslow decided that the army had to fall back to the shelter of Smith’s Trading Post in Coccumscossoc (Wickford), where some resupply ships might have arrived. The English gathered their wounded, the worst being placed on horseback, and fell back toward Wickford. It would not be until 2 AM that the leading units would stumble into the town. Some, losing their way, would not get shelter until 7 AM.

The retreating Indians were driven from the woods about the fort, leaving the English a complete, though costly, victory. They had lost five captains and 20 men and had some 150 wounded that must be carried back to a house some ten miles distant. To the terrors of the battle and fire were added the bitter cold and blinding snow of a New England blizzard through which the English toiled back to Cocumcussa. The hardships of that march took a toll of 30 or 40 more lives. The Indians reported a loss of 40 fighting men and one sachem killed and some 300 old men, women and children burned alive in the wigwams.

Many of the warriors and their families escaped into the frozen swamp. Facing a winter with little food and shelter, the whole surviving Narragansett tribe was forced out of quasi-neutrality some had tried to maintain in the on-going war and joined the fight alongside Philip. The colonists lost many of their officers in this assault and about 70 of their men were killed and nearly 150 more wounded. The dead and wounded colonial militiamen were evacuated to the settlements on Aquidneck Island in Narragansett Bay where they were buried or cared for by many of the Rhode Island colonists until they could return to their homes.

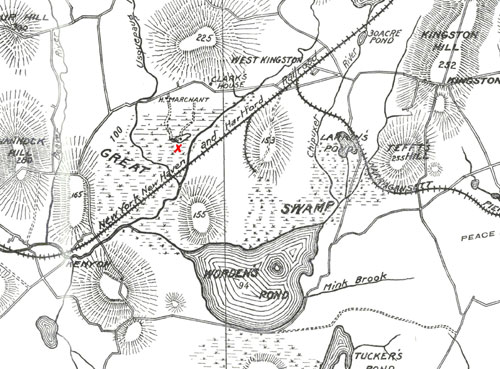

Great Swamp Fight 1906 Map - Rhode Island Society of Colonial Wars' Record of the Unveiling of the Monument Commemorating the Great Swamp Fight, - The site of the Narragansett fort is marked with a red X

A portion of the high ground had been enclosed, and from a careful comparison of the most reliable accounts, it seems that the fortifications were well planned. Mr. Hubbard says: “The Fort was raised upon a Kind of Island of five or six acres of rising Land in the midst of a swamp; the sides of it were made of Palisadoes set upright, the which was compassed about with a Hedg of almost a rod Thickness.” A contemporary writer says: “In the midst of the Swamp was a Piece of firm Land, of about three or four Acres, whereon the Indians had built a kind of Fort, being palisadoed round, and within that a clay Wall, as also felled down abundance of Trees to lay quite round the said Fort, but they had not quite finished the said Work.” It is evident from these, the only detailed accounts, and from some casual references, that the works were rude and incomplete, but would have been almost impregnable to the colonial troops had not the swamp been frozen.

At the corners and exposed portions, rude block-houses and flankers had been built, from which a raking fire could be poured upon any attacking force. Either by chance, or the skill of Peter, their Indian guide, the English seem to have come upon a point of the fort where the Indians did not expect them. Mr. Church, in relating the circumstances of Capt. Gardiner’s death, says that he was shot from that side “next the upland where the English entered the swamp.” The place where he fell was at the “east end of the fort.” The tradition that the English approached the swamp by the rising land in front of the “Judge Marchant” house, thus seems confirmed. This “upland” lies about north of the battlefield.

Thanks for sharing superb informations. Your website is so cool.

Pingback: George Polley | Miner Descent

Pingback: William Beamsley | Miner Descent

Pingback: Capt. John Gorham | Miner Descent

Pingback: John Perkins | Miner Descent

Pingback: Thomas Miner | Miner Descent

Pingback: Walter Palmer | Miner Descent

Pingback: Maj. John Mason | Miner Descent

Pingback: Edward Hazen Sr. | Miner Descent

Pingback: John Boynton | Miner Descent

Pingback: Richard Upham | Miner Descent

Pingback: Joseph Batcheller | Miner Descent

Pingback: Thomas Richardson | Miner Descent

Pingback: Rev. James Fitch | Miner Descent

Pingback: Thomas Huckins | Miner Descent

Pingback: Capt. Jonathan Sparrow | Miner Descent

Pingback: Nehemiah Smith | Miner Descent

Pingback: Jonathan Wilmarth | Miner Descent

Pingback: Daniel Woodward | Miner Descent

Pingback: John Polley Sr. | Miner Descent

Pingback: John Burbeen | Miner Descent

Pingback: Veterans | Miner Descent

Pingback: Samuel Perry | Miner Descent

Pingback: Robert Abell | Miner Descent

Pingback: Thomas Holbrook | Miner Descent

Pingback: Great Swamp Fight – Regiments | Miner Descent

Pingback: Great Swamp Fight – Regiments | Miner Descent

Pingback: Great Swamp Fight – Joshua Tefft | Miner Descent

Pingback: Great Swamp Fight – Aftermath | Miner Descent

Pingback: Great Swamp Fight – Aftermath | Miner Descent

Pingback: Great Swamp Fight | Miner Descent

Pingback: Great Swamp Fight – Regiments | Miner Descent

Pingback: William Chase II | Miner Descent

Pingback: Francis Baker | Miner Descent

Pingback: Joseph Holloway | Miner Descent

Pingback: Favorite Posts 2011 | Miner Descent

Pingback: John Harvey | Miner Descent

Pingback: Francis Wyman Sr. | Miner Descent

Pingback: Edward Wood | Miner Descent

Pingback: Uncas | Miner Descent

Pingback: Uncas and the Miner Ancestors | Miner Descent

Pingback: Francis Brown II | Miner Descent

Pingback: Favorite Posts 2012 | Miner Descent

This account seems highly credible. As a Native myself, the veracity of certain things always rings off key. My Narragansett friend and classmate told me this story, and that his grandfather told him how the elder would go to a place and weep. Sensitives claim to still be able to hear the screams of the burning Indians. So close to Christmas Day, I am comforted that some soldiers questioned their actions, especially the agony of death by fire of innocent children, when The Bible’s teachings conflicted so much with what they had just done.

Im just finding my ancestors where a part of this so called war. More like a massacre. My ancestor was Samuel Perry, he was a soildier in that war. I would like to apologize for my ancestors and all their involvement. Innocent blood was spilt and their voices cry out, women and children. Peace is better then war. They were there in the USA before the white man came. I just sorry, and ask forgiveness for this injustice, on behave of my ancestors. I feel alot of shame for what they did. Thank you, Mary Lynn Humphrey, Khvostova 😦

Pingback: Favorite Posts 2013 | Miner Descent

Is thete any information on hannah cloyce’s husband Daniel Elliott. Im looking for his father and mother and so on. Im a descendant of Daniel Elliott and im working on my family tree. I cant get passed Daniel. Thank you.

Their most be marriage cert. Or court documents or something listing his parents names.

Pingback: A Sublime Autumn Day In A Rhode Island Killing Swamp – Tom Trigo – ephemeral thoughts on the world around us

Pingback: A Sublime Autumn Day In A Rhode Island Killing Swamp – Tom Trigo – ephemeral thoughts on the world around us

My husband’s ancestor, Joshua Teft, killed my ancestor, Capt. Nathanial Seeley as he was entering the fort, fortunately, not before each of them had offspring. Ty for this detailed info.

Does a list of the dead (or participants)exist? So far I have located 8 ancestors who were involved, some of whom I am related to through two or three tree branches.

Pingback: The Great Swamp Fight, Kingston, Rhode Island - Travels With Phil - RhodeislandDigitalNews.com

There are some published accounts that doubt the Great Swamp Fight monument being at the site of the battle. Do you have any current information if there is actually another location?