On 15 Mar 1697, George CORLISS (1617 – 1686)’s daughter Mary Neff was nursing Hannah Dustin who had given birth the week before. They taken prisoner by the Indians in an attack on Haverhill and carried towards Canada.

Hannah Duston (1657 – 1736) was a colonial Massachusetts Puritan woman who escaped Native American captivity by leading her fellow captives in scalping their captors at night. Duston is the first woman honored in the United States with a statue.

Hannah Dustin Statue Penacook New Hampshire

Today, Hannah Dustin’s actions are controversial, with some calling her a hero, but others calling her a villain, and some Abenaki leaders saying her legend is racist and glorifies violence. As early as the 19th Century, Hannah’s legal argument had lost its Old Testament authority and came to be interpreted, or misinterpreted, as a justification for vengeance.

Chief Nancy Lyons of the Coasek tribe of the Abenaki Nation, said using Dustin as a promotional tool not only insults American Indians but glorifies violence.

“It’s not so much because Hannah Duston killed Indians. The biggest issue that I find absolutely appalling is that the promotion that they’re doing is extremely racist – it’s emphasizing violence and they’re promoting that to young people,” Lyons said. “More than being an Indian, being a mother I find it absolutely appalling that a community would promote violence and a violent act in a racist manner to young people today.”

Charles True, speaker of the Abenaki Nation of New Hampshire, said Duston has become a folk legend over the years and her legend bears little resemblance to the actual events of 1697.

“Folk legends rarely represent the actual truth about things,” True said. “In New England history books, our people have not had a fair shake. We were victimized very cruelly by New England people. … It makes you wonder why history books for schoolchildren over the years have made us out to be blood-thirsty savages. Haverhill can do what it pleases with its folk hero. We’re not interested.”

Margaret Bruchak, an Abenaki historian, said in order to properly understand the Duston story, it’s important to understand the Abenaki culture’s view of combat and captivity.

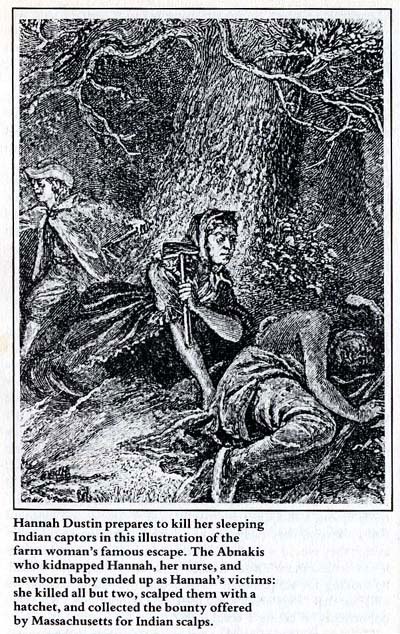

“The whole point of taking a captive was to then transport that person safely. For the whole of that journey they were treated like family,” Bruchak said. “When captives were taken, they were almost immediately handed off from the warriors to individuals who would then look after them. Hannah, we know for a fact, was handed over to an extended family group of two adult men, three women, seven children and one white child.”

That’s why the Abenaki viewed Duston’s actions after she escaped with such horror, she said.

“It’s almost like the Geneva Conventions, when you think about it. Hannah betrayed the Abenaki Geneva Conventions. It wasn’t while she was in the midst of warfare that she did these supposedly brave acts. It was while she was in the care of a family,” Bruchak said. “If she had merely escaped, there probably would be very little story to tell, but the fact that she escaped, then stopped and went back to collect scalps – the bloody-mindedness of it is really quite remarkable. …

“She became a hero because of it. The Colonial Puritan society which saw the killing of white children as an unpardonable sin that required the death penalty saw the killing of Indian children as a glorious act that turns someone into a hero,” she said.

Hannah with Axe

Hannah’s name has been used to sell every conceivable product including a rock concert, liquor and horse racing and still remains extremely attractive to people seeking to prove a genealogical connection. In 2008, after the New Hampshire Historical Society began selling a Hannah Duston bobblehead, one employee has quit and another has refused to sell it. They said they find the Duston doll, as well as another bobblehead of Chief Passaconaway, offensive to Native Americans. The bobblehead is also for sale at the John Greenleaf Whittier Birthplace in Haverhill and the Friends Shop at Haverhill Public Library.

Hannah Dustin Bobblehead

Early nineteenth-century New England, apparently under the impetus of the romantic interest of the past, rediscovered its own colonial history and exploited it in novels and tales. Stories of captivity of the colonists had a wide appeal, not only because they were straight-forward and exciting, but because the ancestors of many New England men and women had been among the captives.

Some even want to make a movie. “It’s the ultimate feminist story,” said Rebecca Day, a Massachusetts native and freelance writer who has done script development for Hallmark Entertainment and Lifetime Television. “It has all the qualities of a hot Lifetime movie. I would pitch it as ‘Ransom’ meets ‘The Crucible.'”

“What interests me is exploring what made her tick,” Day said. “I think the story perfectly illustrates what happens when one’s world turns into chaos. A person really has to go into survival mode, regardless of what role society thinks he or she is supposed to play. Although women at this time were considered second-class citizens, I think it’s funny how many men so easily became her followers and admirers.”

The story of Hannah Dustin is memorable among such accounts because it is both briefer and more violent than most of the narratives. From the beginning it appealed not only to the historical imagination of its readers but to the moral imagination as well. It illustrated the hardihood of New England pioneers but it raised questions about the moral cost of their triumph. As succeeding generations retold Hannah Dustin’s story, it came to illustrate not only frontier conditions during King William’s War, but the shifting judgements and sensibilities about morality and the role of women of later centuries.

Hannah Dustin and Mary Neff take justice into their own hands — Painted in 1847, by Junius Brutus Stearns

Twenty-seven persons were slaughtered, (fifteen of them children) and thirteen captured. The following is a list of the killed:-John Keezar, his father, and son, George; John Kimball and his mother, Hannah ; Sarah Eastman [Daughter of Deborah Corliss and grand daughter of George CORLISS]; Thomas Eaton ; Thomas Emerson, his wife, Elizabeth, and two children, Timothy and Sarah ; Daniel BRADLEY’s son Daniel Bradley, his wife, Hannah (she was also Stephen DOW’s daughter), and two children, Mary and Hannah ; Martha Dow, daughter of Stephen DOW; Joseph, Martha, and Sarah Bradley, children of Joseph Bradley, another son of Daniel BRADLEY ; Thomas and Mehitable Kingsbury [Children of Deborah Corliss and grand daughter of George CORLISS]. ; Thomas Wood and his daughter, Susannah ; John Woodman and his daughter, Susannah; Zechariah White ; and Martha, the infant daughter of Mr. Duston.” Hannah Dustin’s nurse Mary Neff, daughter of our ancestor GEORGE CORLISS, was carried away and helped in the escape by hatcheting her captors. Another captive who later wrote about the adventure and was kidnapped a second time ten years later was Hannah Heath Bradley, wife of Daniel BRADLEY’s son Joseph, daughter of John Heath and Sarah Partridge, and grand daughter of our ancestor Bartholomew HEATH.

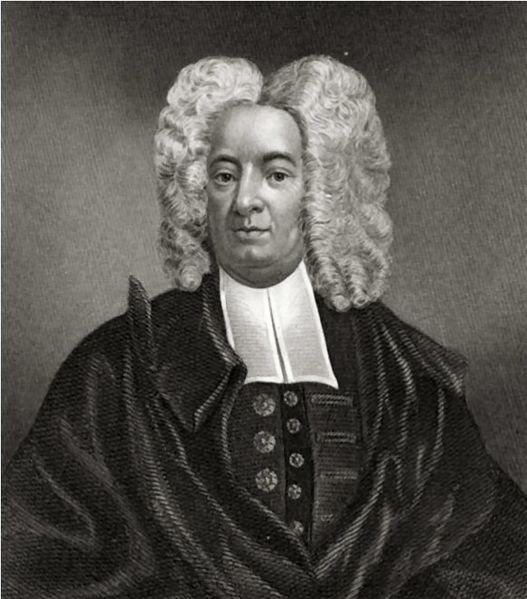

Cotton Mather Portrait c. 1700

The account begins with Cotton Mather, not only because he heard the story from Hannah herself and was the first to record it, but because his account in the Magnalia Christi Americana (1702) contains the germs of all the moral and social questions to which later writers would respond: Is the killing of one’s Indian captors justified? Is killing squaws and children ever justifiable? Is killing Christian (although Catholic) Indians justifiable? Is scalping Indian victims and collecting a bounty on the scalps justifiable? Should a wife and mother be judged by standards not applied to men? And finally, was Hannah admirable as well as courageous?

Mather’s account in the Magnalia served as a primary source for all except two of the subsequent retellings.

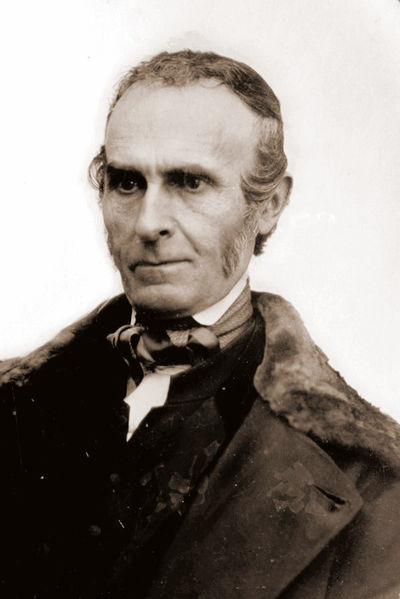

John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892)

John Greenleaf Whittier popularized the incident in “A Mother’s Revenge” . His story differed significantly from the Mather account, apparently reflecting both local tradition and conscious literary manipulation of his material. His theme was the resolution created in a woman’s character by the exigencies of the frontier. In Whit tier’s version of the story, Hannah heroically sends her husband to protect the children. He thus adds luster to Hannah’s character and redeems Thomas Dustin from possible charges that he deserted his wife and infant daughter.

Statue of Hannah Dustin in Haverhill, Mass

George Chase, in the History of Haverhill (1861), brought together the Mather, Sewall, and Mirick accounts, supplementing them by use of the town records. He corrected Mirick at some points and provided a definitive recital of the Indian raid and its aftermath. He reprints Mather’s Magnalia account in its entirety because he says it is the most reliable, Mather having “heard the story direct from the lips of Mrs. Dustin.” Then, having discussed the location of the Dustin house, Chase deliberately and needlessly turns to compare Hannah’s deeds unfavorably with those of her husband. He reasons that Hannah attacked “twelve sleeping savages, seven of whom were children, and but two of whom were men. It was not with her a question of life or death, but of liberty and revenge.”

In this instance Chase, with the Mather account directly before him, discarded both of Mather’s justifications for the killings. Chase judges Hannah on the basis of a revenge motive that he, Whittier, and Bancroft ascribe to her. The only support for such an interpretation is Hannah’s explanation that being where she had not her own life secured to her by law she felt it lawful to kill the Indians, “by whom her child had been butchered.” The context in which these words appear suggests that Hannah is not seeking vengeance but invoking the Old Testament law of “an eye for an eye” which, for people who consciously formed their legal system upon Biblical law, represented not revenge but justice.

As time passed Hannah’s legal argument lost its Old Testament authority and came to be interpreted, or misinterpreted, as a justification for vengeance. As Hannah’s historians became further removed from frontier life, they increasingly admired women rather for their frailty than for their hardihood. The new crop of authors, fascinated by Hannah’s story, yet deploring her conduct, insisted upon the harsher details of her exploit, while religious ardor and ethical judgement faded before social convention.

Detailed Account

Here’s a more detailed account of Hannah and Mary from The Duston / Dustin Family, Thomas and Elizabeth (Wheeler) Duston and their descendants. and The Story of Hannah Duston Published by the Duston-Dustin Family Association, H. D. Kilgore Historian Haverhill Tercentenary – June, 1940. I’ve kept most of the 19th Century language, only removing a few breathless adverbs, opinionated adjectives and changing some pejorative nouns.

On March 14, 1697, Thomas and Hannah Duston lived in a house on the west side of the Sawmill River in the town of Haverhill. This house was located near the great Duston Boulder and on the opposite side of Monument Street.

Their twenty years of married life had brought them material prosperity, and of the twelve children who had been born to them during this period, eight were living. Thomas, who was quite a remarkable man, – a bricklayer and farmer, who, according to tradition, even wrote his own almanacs, and wrote them on rainy days, – was beginning to have time to devote to town affairs, and had just completed a term as Constable for the “west end” of the town of Haverhill.

He was at this time engaged in the construction with bricks from his own brickyard of a new brick house about a half mile to the northwest of his home to provide for the needs of his still growing family, for Baby Martha had just made her appearance on March 9.

Under the care of Mrs. Mary Neff, (daughter of George CORLISS and widow of William Neff) both mother and child were doing well, the rest of the family were in good health, his material affairs were prospering, and it was undoubtedly with a rather contented feeling that Thomas, to say nothing of his family, retired to rest on the eve of that fateful March 15, 1697, little knowing what horrors the morrow was to bring.

Of course, there was always the fear of Indians. However, since the capture in August of the preceding year, of Jonathan Haynes and his four children while picking peas in a field at Bradley’s Mills, near Haverhill, nothing had happened, and apprehensions of any further attacks were gradually being lulled. Besides, less than a mile on Pecker’s Hill, was the garrison of Onesiphorus Marsh, one of six established by the town containing a small body of soldiers. It was believed that there was little ground for uneasiness.

But this was only a false security. Count Frontenac, the Colonial Governor of Canada, was using every means at his disposal to incite the Indians against the English as part of his campaign to win the New World for the French King. The latter, due to the need for troops in Europe, where the war known as King William’s War was going on, was unable to send many to help Frontenac. So, with propaganda and gifts, the French Governor had allied the tribes to the French cause and bounties had been set on English scalps and prisoners. Every roving band of Indians was determined to get its share of these, and even now, such a band was in the woods near Haverhill, preparing for a lightning raid on the town with the first light of dawn. The squaws and children were left in the forest to guard their possessions, while the Indian warriors moved stealthily towards the house of Thomas and Hannah Duston, the first attacked. [The Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 ended the war between the two colonial powers, reverting the colonial borders to the status quo ante bellum. The peace did not last long, and within five years, the colonies were embroiled in the next phase of the French and Indian Wars, Queen Anne’s War.]

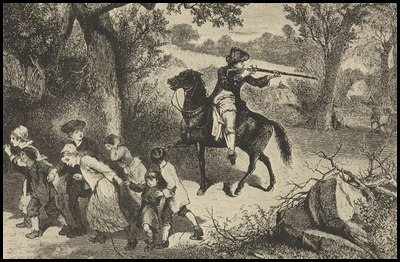

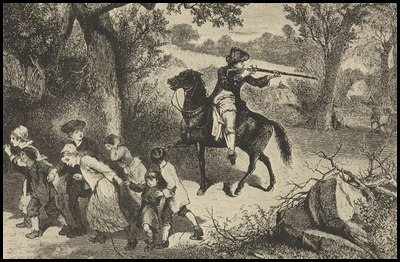

Early the next morning, Thomas, at work near the house, suddenly spied the approaching Indians. Instantly seizing his gun he mounted his horse and raced for the house, shouting a warning which started the children towards the garrison, while he dashed into the house hoping to save his wife and the baby. Quickly seeing that he was too late, and doubtless urged by Hannah, he rode after the children, resolving to escape with at least one. On overtaking them, finding it impossible to choose between them, he resolved, if possible, to save them all. A few of the Indians pursued the little band of fugitives, firing at them from behind trees and boulders, but Thomas, dismounting and guarding the rear, held back the savages from behind his horse by threatening to shoot whenever one of them exposed himself. Had he discharged his gun they would have closed in at once, for reloading took considerable time. He was successful in his attempt, and all reached the garrison safely, the older children hurrying the younger along, probably carrying them at times. This was probably the garrison of Onesiphorus March on Pecker’s Hill.

Escape of Thomas Dustin & children. Source: Some Indian Stories of Early New England, 1922

Meanwhile a fearful scene was being enacted in the home. Mrs. Neff, trying to escape with the baby, was easily captured. Invading the house, the Indians forced Hannah to rise and dress herself. Sitting despairingly in the chimney, she watched them rifle the house of all they could carry away, and was then dragged outside while they fired the house, in her haste forgetting one shoe. A few of the Indians then dragged Hannah and Mrs. Neff, who carried the baby, towards the woods, while the rest of the band, rejoined by those who had been pursing Thomas and the children, attacked other houses in the village, killing twenty-seven and capturing thirteen of the inhabitants.

Hannah Dustin Memorial Bas Relief 1.

Finding that carrying the baby was making it hard for Mrs. Neff to keep up, one of the Indians seized it from her, and before its mother’s horrified eyes dashed out its brains against an apple tree. The Indians, forcing the two women to their utmost pace, at last reached the woods and jointed the squaws and children who had been left behind the night before. Here they were soon after joined by the rest of the group with their plunder and other captives.

Fearing a prompt pursuit, the Indians immediately set out for Canada with their booty. Some of the weaker captives were knocked on the head and scalped, but in spite of her condition, poorly clad and partly shod, Hannah, doubtless assisted by Mrs. Neff, managed to keep up, and by her own account marched that day “about a dozen miles”, a remarkable feat. During the next few days they traveled about a hundred miles through the unbroken wilderness, over rough trails, in places still covered with the winter’s snow, sometimes deep with mud, and across icy brooks, while rocks tore their half shod feet and their poorly clad bodies suffered from the cold – a terrible journey.

Near the junction of the Contoocook and Merrimack rivers, twelve of the Indians, two men, three women, and seven children, taking with them Hannah, Mrs. Neff and a boy of fourteen years, Samuel Lennardson (who had been taken prisoner near Worcester about eighteen months before), left the main party and proceeded toward what is now Dustin Island, situated where the two rivers unite, near the present town of Penacook, N.H. This island was the home of the Indian who claimed the women as his captives, and here it was planned to rest for a while before continuing on the long journey to Canada.

This Indian family had been converted by the French priests at some time in the past, and was accustomed to have prayers three times a day, – in the morning, at noon and at evening, – and ordinarily would not let their children eat or sleep without first saying their prayers. Hannah’s master, who had lived in the family of Rev. Mr. Rowlandson of Lancaster some years before told her that “when he prayed the English way he thought that it was good, but now he found the French way better.” They tried, however, to prevent the two women from praying, but without success, for as they were engaged on the tasks set by their master, they often found opportunities. Their Indian master would sometimes say to them when he saw them dejected, “What need you trouble yourself? If your God will have you delivered, you shall be so!”

[Mary (White) Rowlandson (c. 1637 – Jan 1711) was a colonial American woman who was captured by Indians during King Philip’s War and endured eleven weeks of captivity before being ransomed. After her release, she wrote a book about her experience, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, which is considered a seminal work in the American literary genre of captivity narratives.

During the long journey Hannah was secretly planning to escape at the first opportunity, spurred by the tales with which the Indians had entertained the captives on the march, picturing how they would be treated after arriving in Canada, stripped and made to “run the gauntlet”; jeered at and beaten and made targets for the young Indians’ tomahawks; how many of the English prisoners had fainted under these tortures; and how they were often sold as slaves to the French. These stories, added to her desire for revenging the death of her baby and the cruel treatment of their captors while on the march, made this desire stronger. When she learned where they were going, a plan took definite shape in her mind, and was secretly communicated to Mrs. Neff and Samuel Lennardson.

Samuel, who was growing tired of living with the Indians, and in whom a longing for home had been stirred by the presence of the two women, the next day casually asked his master, Bampico, how he had killed the English. “Strike ‘em dere,” said Bampico, touching his temple, and then proceeded to show the boy how to take a scalp. This information was communicated to the women, and they quickly agreed on the details of the plan. They arrived at the island some time before March 30, 1697.

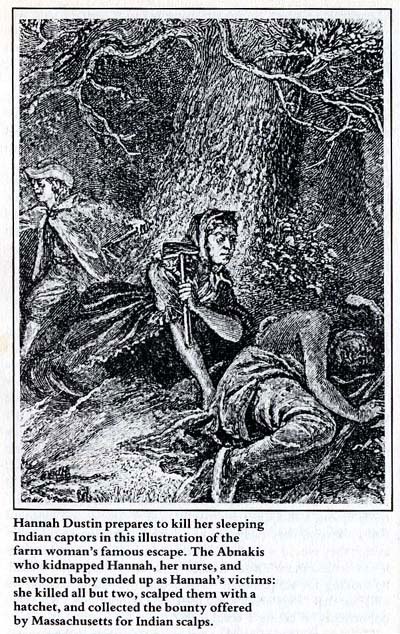

After reaching the island, the Indians grew careless. The river was in flood. Samuel was considered one of the family, and the two women were considered too worn out to attempt escape, so not watch was set that night and the Indians slept soundly. Hannah decided that the time had come.

Hannah Dustin Memorial Bas Relief 2

Shortly after midnight she woke Mrs. Neff and Samuel. Each, armed with a tomahawk, crept silently to a position near the heads of the sleeping Indians – Samuel near Bampico and Hannah near her master. At a signal from Hannah the tomahawks fell, and so swiftly and surely did they perform their work of destruction that ten of the twelve Indians were killed outright, only two – a severely wounded squaw and a boy whom they had intended to take captive – escaped into the woods. According to a deposition of Hannah Bradley in 1739 (History of Haverhill, Chase, pp. 308-309),

“above penny cook the Deponent was forced to travel farther than the rest of the captives, and the next night but one there came to us one Squaw who said that Hannah Dustan and the aforesaid Mary Neff assisted in killing the Indians of her wigwam except herself and a boy, herself escaping very narrowly, shewing to myself & others seven wounds as she said with a Hatched on her head which wounds were given her when the rest were killed.”

Hastily piling food and weapons into a canoe, including the gun of Hannah’s late master and the tomahawk with which she had killed him, they scuttled the rest of the canoes and set out down the Merrimack River.

Original Gun taken by Hannah Dustin

Suddenly realizing that without proof their story would seem incredible, Hannah ordered a return to the island, where they scalped their victims, wrapping the trophies in cloth which had been cut from Hannah’s loom at the time of the capture, and again set out down the river, each taking a turn at guiding the frail craft while the others slept. [this was Hannah’s explanation, Is it credible to you?]

Hannah Dustin and Mary Neff make their escape

Thus, traveling by night and hiding by day, they finally reached the home of John Lovewell in old Dunstable, now a part of Nashua, N.H. Here they spent the night, and a monument was erected here in 1902, commemorating the event. The following morning the journey was resumed and the weary voyagers at last beached their canoe at Bradley’s Cove, where Creek Brook flows into the Merrimack. Continuing their journey on foot, they at last reached Haverhill in safety. Their reunion with loved ones who had given them up for lost can better be imagined than described.

Hannah Dustin Detail

Thomas took his wife and the others to the new house which he had been building at the time of the massacre, and which was now completed. Here for some days they rested. The fear induced by the massacre caused Haverhill to at once establish several new garrison houses. One of these was the brick house which Thomas was building for his family at the time of the massacre. This was ordered completed, and though the clay pits were not far from the home, a guard of soldiers was placed over those who brought clay to the house. The order establishing Thomas Duston’s house as a garrison was dated April 5, 1697. He was appointed master of the garrison and assigned Josiah HEATH, Sen., Josiah Heath Jun., Joseph Bradley, John Heath, Joseph Kingsbury, and Thomas Kingsbury as a guard.

Dustin Garrison

In 1694 a bounty of fifty pounds had been placed on Indian scalps, reduced to twenty-five pounds in 1695, and revoked completely on Dec. 16, 1696.

Hannah had risked precious time to gain those scalps. The explanation sometimes given later, that her story would not be believed without evidence, is patently false. If her credibility were the only issue at stake, sooner or later there would be corroborative accounts. Actually, Hannah Bradley, another Haverhill woman, was a captive in the camp where the wounded squaw sought refuge. But to collect a scalp bounty Hannah needed to produce the scalps.

Thomas Duston believed that the act of the two women and the boy had been of great value in destroying enemies of the colony, who had been murdering women and children, and decided that the bounty should be claimed. So he took the two women and the boy to Boston, where they arrived with the trophies on April 21, 1697.

Here he filed a petition to the Governor and Council, which was read on June 8, 1697 in the House

To the Right Honorable the Lieut Governor & the Great & General assembly of the Province of Massachusetts Bay now convened in BostonThe Humble Petition of Thomas Durstan of Haverhill Sheweth That the wife of ye petitioner (with one Mary Neff) hath in her Late captivity among the Barbarous Indians, been disposed & assisted by heaven to do an extraordinary action, in the just slaughter of so many of the Barbarians, as would by the law of the Province which——–a few months ago, have entitled the actors unto considerable recompense from the Publick.

That tho the———-of that good Law————–no claims to any such consideration from the publick, yet your petitioner humbly—————-that the merit of the action still remains the same; & it seems a matter of universal desire thro the whole Province that it should not pass unrecompensed.

And that your petitioner having lost his estate in that calamity wherein his wife was carried into her captivity render him the fitter object for what consideration the public Bounty shall judge proper for what hath been herein done, of some consequence, not only unto the persons more immediately delivered, but also unto the Generall Interest

Wherefore humbly Requesting a favorable Regard on this occasion

Your Petitioner shall pray &c

Thomas Du(r)stun

Despite the missing words its purport is clear. Hannah has performed a service to the community and deserves an appropriate expression of gratitude. It also implies a justification for killing the squaws and children, if any justification were needed when the captives’ safety depended upon several hours head start.

The same day the General Court voted payment of a bounty of twenty-five pounds “unto Thomas Dunston of Haverhill , on behalf of Hannah his wife”, and twelve pounds ten shillings each to Mary Neff and Samuel. This was approved on June 16, 1697, and the order in Council for the payment of the several allowances was passed Dec. 4, 1697. (Chapter 10, Province Laws, Mass. Archives.)

While in Boston Hannah told her story to Rev. Cotton Mather, whose morbid mind was stirred to its depths. He perceived her escape in the nature of a miracle, and his description of it in his “Magnalia Christi Americana” is extraordinary, though in the facts correct and corroborated by the evidence.

In Samuel Sewall’s Diary, Volume 1, pages 452 and 453, we find the following entry on May 12, 1697:

Fourth-day, May12….Hanah Dustin came to see us:….She saith her master, who she kill’d did formerly live with Mr. Roulandson at Lancaster: He told her, that when he pray’d the English way, he thought that was good: but now he found the French way was better. The single man shewed the night before, to Saml Lenarson, how he used to knock Englishmen on the head and take off their Scalps: little thinking that the Captives would make some of their first experiment upon himself. Sam. Lenarson kill’d him.

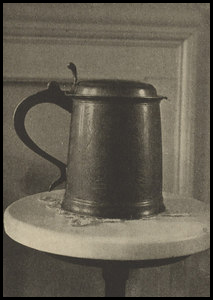

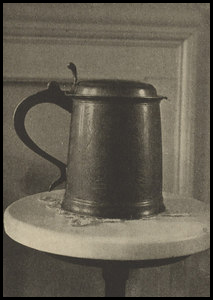

This remarkable exploit of Hannah Duston, Mary Neff, and Samuel Lennardson was received with amazement throughout the colonies, and Governor Nicholson of Maryland sent her a suitably inscribed silver tankard.

Dustin Tankard, A gift from the Gov. of Maryland to Hannah Dustin in 1697. In possession of the Haverhill Historical Society, Hav. Mass. Source: Some Indian Stories of Early New England, 1922

Historian Kathryn Whitford notes that the Abenaki Indians themselves didn’t take revenge on Hannah, though they had the opportunity and there are a good many recorded instances of Indian vengeance upon men who had betrayed them. She concludes “It almost seems as though the Indians recognized that they and Hannah approached border warfare in the same spirit and that they owed her no grudge.”

Sources:

Hannah Dustin: The Judgement of History By Kathryn Whitford Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

http://quod.lib.umich.edu/a/amverse/BAH8738.0001.001/1:20?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

http://www.colby.edu/academics_cs/museum/upload/pdf-western-expansion.pdf

http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2199&dat=19971129&id=J7oyAAAAIBAJ&sjid=hegFAAAAIBAJ&pg=6482,4822396

http://www.thehammersmithgroup.com/about/images/reconsidering.pdf

http://www.eagletribune.com/x1876255787/Hannah-Duston-Heroine-or-villainess-Festival-posters-rekindle-age-old-debate/