John FRENCH Sr. (1622 – 1697) was Alex’s 10th Great Grandfather, one of 2,048 in this generation of the Shaw line.

John French Sr was was baptized in St. Edmund’s, Assington, Suffolk, England on 26 May 1622. His parents were Thomas FRENCH (1584 – 1639) and Susan RIDDLESDALE (1584 – 1658). He immigrated with his parents about 1637. His older brother Thomas came over first with the Winthrop fleet. His sisters Dorcas and Susan immigrated about 1633 to serve as maids to John Winthrop. He married Freedom KINGSLEY about 1654. John died on 1 Feb 1697 in Northampton, Mass.

Freedom Kingsley was born about 1636 in Dorchester, Mass. Her parents were John KINGSLEY and Elizabeth STOUGHTON. Before she married John, Freedom was a servant of William Lane (Suff. I :99)

The will of Wm Lane of Dorchester, mentions Thomas Rider my Sonne in Lawe and my daughter Elizabeth his wife, & his children; sonne Thomas Linckhorne of Hingham; Sonne George Lane of Hingham; sonne Nathaniell Baker of Hingham; sonne Andrew Lane of Hingham; Mary Long my daughter; ffredome Kingley my faithfull servant; Brethren Joseph ffaraworth & John Wiswall Exors. Made 28 Feb. 1650.

Freedom died on 16 Jul 1689 in Northampton, Mass.

Children of John and Freedom:

| Name | Born | Married | Departed | |

| 1. | John FRENCH Jr. | 28 Feb 1654/55 Ipswich, Mass. | Hannah PALMER 27 Nov 1676 Rehoboth, Mass |

24 Feb 1723/24 Rehoboth, Mass. |

| 2. | Deacon Thomas French | 25 May 1657 Ipswich |

Mary Catlin 18 Oct 1683 Northampton, Mass . Hannah (Edwards) Stebbins |

3 Apr 1733 Deerfield, Mass |

| 3. | Noe French | 27 Feb 1659/60 | Died Young | |

| 4. | Mary French | 27 Feb 1659/60 | Samuel Stebbins 4 Mar 1677/78 Northampton |

26 Jan 1696 Northampton, Hampshire, MA |

| 5. | Samuel French | 26 Feb 1661/62 | Unmarried | 8 Sep 1683 |

| 6. | Infant Daughter | 1 Apr 1664 Ipswich |

1 Apr 1664 | |

| 7. | Hannah French | 8 Mar 1664/65 Ipswich |

Francis Keet | 25 JUL 1711 Northampton, Hampshire, MA |

| 8. | Jonathan French | 30 Jul 1667 Ipswich |

Sarah Warner 1692 Hadley, Hampshire, Mass |

17 Feb 1714 Northampton, Hampshire, MA |

| 9. | Elizabeth French | 9 Oct 1673 Ipswich |

Samuel Pomeroy c. 1690 prob. Northampton |

2 Jun 1702 Northampton, Hampshire, MA |

x

The first record of John French in America was in Dorcester, Mass was first recorded in Dorchester on 27 Jan 1642/43 after his arrival in Boston.

He came to Northampton sometime between 1682 and 1690, probably from Ipswich, where he had been a farmer. At least two of his children with Freedom Kingsley were born in Rehoboth.

Savage –

JOHN, Northampton, came a. 1676, from Rehoboth, with w. d. of John Kingsley, and ch. John, Thomas, Samuel, and Jonathan, the first three of wh. took o. of alleg. 8 Feb. 1679; beside three ds. Mary, w. of Samuel Stebbins, m. 4 Mar. 1678, wh. d. bef. her f.; Hannah, w. of Francis Keet; and Elizabeth w. of Samuel Pomeroy. Perhaps he was s. of John of Dorchester; certain. he d. 1 Feb. 1697. Samuel d. prob. unm. 8 Sept. 1683.2

John French of Ipswich was a Denison subscriber in 1648, to pay this tax he must have been of age and therefore born before 1627, which agrees with the Assington record.

Four deeds of John French of Ipswich, Taylor, and Freedom his wife, as well as the similarity of names of children to those of John French of Northampton, indicate the identity of the two families.

John French was entitled to a share in Plumb Island in 1664.

In p’snce of Thomas Wiswall, ffreedome Kingsley. Proved 6 July 1654 by Thomas Wiswall who deposed.

(Ipswich Deed IV : 99)

I John French of Ipswich . . . Tayler … for forty five pounds . . . payd unto me by Thomas Lull of the same Towne weaver . . . sell . . . my now dwelling house and land . . . with barne, out houses, yards, orchyards, Gardens, fences, with all . . . apptenances . . . containing by estimation two acres . . . scituate … in Ipswich . . . Haveing the land of Thomas Mattcalfe toward the south, the land of Joseph Quilter toward the west, John Pindars land toward the north, the streate or way toward the east. To have and to hold . . . and peaceably to possess . . . from the first day of June next coming which will be in the yeare 1678 Thence forward forever . . . the eight of June Anno Dom 1677. John French and a seale

ffreedom French

Recorded June 22th, 1677.

Witnesses, Grace Fitt & a marke

Robert Lord.

John French acknowledged this deed and Freedom his wife did freely resigne her interest of Dowrye in the land and House herein conveyed . . . June 21 :1677.

(Ipswich Deed IV : 102)

… I John French of Ipswich. . . Taylor for . . . sixteene pounds . . . payd by Robert Lord Jun’ of Ipswich . . . marshall . . . Have granted … a p’cell of Land being part of my planting lott by estimation five acres … on the North syde the River … at the time of the sale of the premisses . . . the sayd John is the true owner . . .

In wittnes whereof I the sayd John French with the consent of Freedome my wife have hereunto set my hand … the 25th of June . . . Anno Dom 1677.

Robert Lord, Senior; Samuel Chapman. Recorded Aug. 16,1677.

(Ipswich Deed IV : 110)

. . . I John French of Ipswich . . . Tayler . . . for . . . fifteene pounds . . . payd by Edmond Heard of the same Towne . . . Have . . . sold . . . a parcell of Land lyeing . . . within the comon field on the North Syde the River containeing three acres with all . . . the apptenances … 14 day of September . . . Anno Dom 1677. In presence of Daniel Warner sen’; John Potter.

John French acknowledged this writing to be his act & deed & Freedome his wife did freely resigne her thirds or Interest of Dowry Sept. 20: 77. Recorded Octob: 23, 1677.

(Ipswich Deed IV : 486)

… I John French of Ipswich . . . Taylour and Freedom my wife in consideration of full satisfaction . . . payd by . . . Anthony Potter of the same town . . . planter . . . have sold . . . my parcell of marsh & Thatch being my second division in the marsh called the hundreds . . . also three acres more or less of Basterd marsh lyeing in Ipswich in the marsh commonly called Reedy marsh bounded with the Land of Capt. John Appleton toward the west, by a ditch and with land of Ensigne Thomas French toward the Northeast, and with land of Mr Robert Paine in pt and with land of Joseph Quilter in pt, toward the South, being a try angle lott . . . dated the fourteenth day of this Instant June . . . 1677.John French and a seale.

Freedome French and a seale.

In presence of John Denison Sen’; John Brewer Sen’.

Recorded decemb 12: 1682.

Children

1. John FRENCH Jr. (See his page)

2. Thomas French

Thomas’ wife first wife Mary Catlin was born 10 Jul 1666 in Wethersfield, Hartford, CT. Her parents were John Catlin and Mary Baldwin. Mary died 9 Mar 1704 in Deerfield, Franklin, Mass.

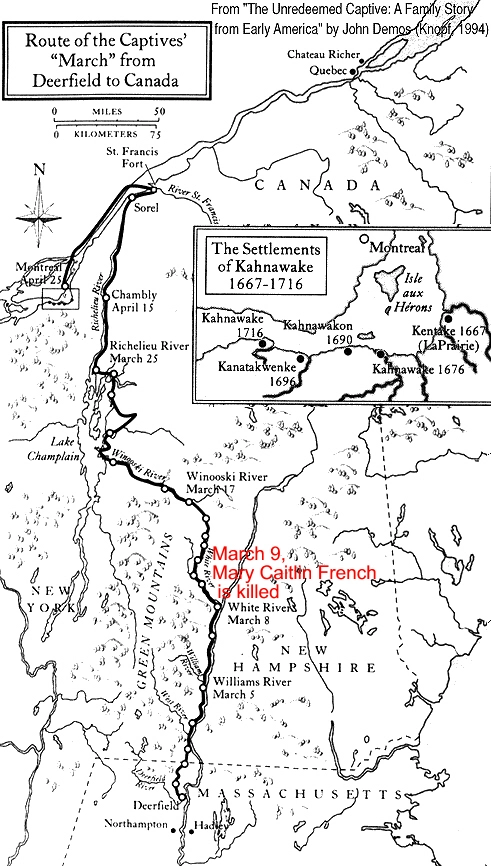

No family suffered more than John Catlin’s in the destruction of Deerfield, Massachusetts during the Indian Massacre of 29 February, 1703/4. He was killed trying to protect his home. His sons Joseph and Jonathan were also killed. His married daughters Mary French and Elizabeth Catlin Corse were killed during the subsequent march to Canada. His wife, Mary, “being held with the other prisoners in John Sheldon‘s house, gave a cup of water to a young French officer who was dying. He was perhaps a brother of Hertel de Rouville. May it not have been gratitude for this act that she was left behind when the order came to march? She died of grief a few weeks later.”

Thomas’ second wife Hannah Atkins was born xx. She was the widow of Joseph Edwards, and of Benoni Stebbins, who was also killed at the Deerfield Massacre. Hannah died in 1737.

Thomas lived for a time in Northampton, where he came with his parents early in his life. Later settled in Deerfield, MA. and was Deacon of the Deerfield Church. He was blacksmith, town clerk and deacon. He and all his family were taken in the Deerfield raid of 1704. The raiders destroyed 17 of the village’s 41 homes, and looted many of the others. Thomas’ house was not burned, so the town records were saved. He married Mary Catlin married 18 October 1683. She was killed on the trip on 9 March 1703/04. He and their two eldest children were redeemed in 1706. He married again to Hannah Edwards 9 Mar 1704 in Ipswich, Essex, Mass and died in 1733.

Deacon Thomas French Gravestone — Old Deerfield Burying Ground , Deerfield, Franklin County, Mass.

Here lyeth the body

of Deacon Thomas

French who dyed

April ye 5th 1733

Aged 76 Years

Blessed are ye dead

Who dye in the Lord

Children of Thomas and Mary:

i. Mary French (8 Mar 1685 in Deerfield, Mass – 12 Mar 1685 in Deerfield)

ii. Mary French (9 Nov 1686 in Deerfield, MA – 24 Mar 1758 in Bolton, Tolland, CT) Carried to Canada 1704. Redeemed with father in 1706, at age 19.

iii. Thomas French , Jr. (2 Nov 1689 in Deerfield, MA – 26 Jun 1759 in Deerfield, MA) Redeemed with father and sister Mary in 1706, probably brought back by Ens. John Sheldon

iv. Freedom French (20 Nov 1692 in Deerfield, Franklin, MA – 6 Oct 1757 in Montréal, Ile de Montréal, Quebec) Freedom was eleven when she was carried to Canada. She was placed in the family of Monsieur Jacques Le Ber, merchant of Montreal, and on Tuesday, the 6th of April, 1706, Madame Le Ber had her baptized anew by Father Meriel, under the name of Marie Françoise, the name of the Virgin added to that of her godmother, being substituted for the Puritanic appellation of Freedom, by which she had been known in Deerfield. She signs her new name, evidently with difficulty, to this register, and never again does she appear as Freedom French. She was often recorded as a guest at the marriages of her English friends. Two years after her sister’s marrage, on the 6th of February, 1713 at the age of twenty-one, Marie Françoise French married Jean Daveluy, ten years older than herself, a relative of Jacques Le Roi, her sister’s husband. Daveluy could not write, but here, appended to the marriage register, I find for the last time the autographs of the two sisters written in full, Marie Françoise and Marthe Marguerite French.

v. Marguerite Martha French (12 May 1695 in Deerfield, MA Baptême: 23-02-1707, Montréal – 1 May 1762 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada) Martha was given by her Indian captors to the Sisters of the Congregation at Montreal. On the 23d of January, 1707, she was baptized sous condition, receiving from her god-mother the name of Marguerite in addition to her own. On Tuesday, November 24, 1711, when about sixteen., she was married by Father Meriel to Jacques Roi, aged twenty-two, of the village of St. Lambert, in the presence of many of their relatives and friends. Jacques Roi cannot write his name, but the bride, Marthe Marguerite French, signs hers in a bold, free hand, which is followed by the dashing autograph of the soldier, Alphonse de Tonty; and Marie Françoise French, now quite an adept in forming the letters of her new name, also signs. On the third of May, 1733, just one month from the day of her father’s death in Deerfield, Martha Marguerite French, widow of Jacques Roi, signed her second marriage contract, and the following day married Jean Louis Ménard, at St. Laurent, a parish of Montreal.

vi. Abigail French (28 Feb 1698 Deerfield, MA – in Caughnawaga, a village of the Mohawk nation inhabited from 1666 to 1693, now an archaeological site near the village of Fonda, New York. lived as an Indian, never married.)

vii. John French (1 Feb 1704 Deerfield, Franklin, MA – 29 Feb 1704 Killed in Deerfield Raid)

The Raid on Deerfield occurred during Queen Anne’s War on February 29, 1704, when French and Native American forces under the command of Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville attacked the English settlement at Deerfield, Massachusetts just before dawn, burning part of the town and killing 56 villagers.

Minor raids against other communities convinced Governor Joseph Dudley to send 20 men to garrison Deerfield in February. These men, minimally trained militia from other nearby communities, had arrived by the 24th, making for somewhat cramped accommodations within the town’s palisade on the night of February 28. In addition to these men, the townspeople mustered about 70 men of fighting age; these forces were all under the command of Captain Jonathan Wells.

The Connecticut River valley had been identified as a potential raiding target by authorities in New France as early as 1702. The forces for the raid had begun gathering near Montreal as early as May 1703, as reported with reasonable accuracy in English intelligence reports. However, two incidents intervened that delayed execution of the raid. The first was a rumor that English warships were on the Saint Lawrence River, drawing a significant Indian force to Quebec for its defense. The second was the detachment of some troops, critically including Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville, who was to lead the raid, for operations in Maine (including a raid against Wells that raised the frontier alarms at Deerfield). Hertel de Rouville did not return to Montreal until the fall.

The force assembled at Chambly, just south of Montreal, numbered about 250, and was composed of a diversity of personnel. There were 48 Frenchmen, some of them Canadien militia and others recruits from the troupes de la marine, including four of Hertel de Rouville’s brothers. The French leadership included a number of men with more than 20 years experience in wilderness warfare. The Indian contingent included 200 Abenakis, Iroquois, Wyandots, and Pocumtucs, some of whom sought revenge for incidents that had taken place years earlier. These were joined by another 30 to forty Pennacooks led by sachem Wattanummon as the party moved south toward Deerfield in January and February 1704, raising the troop size to nearly 300 by the time it reached the Deerfield area in late February.

The expedition’s departure was not a very well kept secret. In January 1704, New York’s Indian agent Pieter Schuyler was warned by the Iroquois of possible action that he forwarded on to Governor Dudley and Connecticut’s Governor Winthrop; further warnings came to them in mid-February, although none were specific about the target.

The raiders left most of their equipment and supplies 25 to 30 miles north of the village before establishing a cold camp about 2 miles from Deerfield on February 28, 1704. From this vantage point they observed the villagers as they prepared for the night. Since the villagers had been alerted to the possibility of a raid, they all took refuge within the palisade, and a guard was posted.

The raiders had noticed that there were snow drifts all the way to the top of the palisade; this greatly simplified their entry into the fortifications just before dawn on February 29. They carefully approached the village, stopping periodically so that the sentry might confuse the noises they made with more natural sounds. A few men climbed over the palisade via the snow drifts and then opened then north gate to admit the rest. Primary sources vary on the degree of alertness of the village guard that night; one account claims he fell asleep, while another claims that he discharged his weapon to raise the alarm when the attack began, but that it was not heard by many people. As the Reverend John Williams later recounted, “with horrid shouting and yelling”, the raiders launched their attack “like a flood upon us.”

The raiders’ attack probably did not go exactly as they had intended. In attacks on Schenectady, New York and Durham, New Hampshire in the 1690s (both of which included Hertel de Rouville’s father), the raiders had simultaneously attacked all of the houses; at Deerfield, this did not happen. Historians Haefeli and Sweeney theorize that the failure to launch a coordinated assault was caused by the wide diversity within the attacking force.

French organizers of the raid drew on a variety of Indian populations, including in the force of about 300 a number of Pocumtucs who had once lived in the Deerfield area. The diversity of personnel involved in the raid meant that it did not achieve full surprise when they entered the palisaded village. The defenders of some fortified houses in the village successfully held off the raiders until arriving reinforcements prompted their retreat. More than 100 captives were taken, and about 40 percent of the village houses were destroyed.

The raiders swept into the village, and began attacking individual houses. Reverend Williams’ house was among the first to be raided; Williams’ life was spared when his gunshot misfired, and he was taken prisoner. Two of his children and a servant were slain; the rest of his family and his other servant were also taken prisoner. Similar scenarios occurred in many of the other houses. The residents of Benoni Stebbins’ house, which was not among the early ones attacked, resisted the raiders’ attacks, which lasted until well after daylight. A second house, near the northwestern corner of the palisade, was also successfully defended. The raiders moved through the village, herding their prisoners to an area just north of the town, rifling houses for items of value, and setting a number of them on fire.

As the morning progressed, some of the raiders began moving north with their prisoners, but paused about a mile north of the town to wait for those that had not yet finished in the village. The men in the Stebbins house kept the battle up for two hours; they were on the verge of surrendering when reinforcements arrived. Early in the raid, young John Sheldon managed to escape over the palisade and began making his way to nearby Hadley to raise the alarm there. The fires from the burning houses had already been spotted, and “thirty men from Hadley and Hatfield” rushed to Deerfield. Their arrival prompted the remaining raiders to flee, some of whom abandoned their weapons and other supplies in a panic.

The sudden departure of the raiders and the arrival of reinforcements raised the spirits of the beleaguered survivors, and about 20 Deerfield men joined the Hadley men in chasing after the fleeing raiders. The English and the raiders skirmished in the meadows just north of the village, where the English reported “killing and wounding many of them”. However, the pursuit was conducted rashly, and the English soon ran into an ambush prepared by those raiders that had left the village earlier. Of the 50 or so men that gave chase, nine were killed and several more were wounded. After the ambush they retreated back to the village, and the raiders headed north with their prisoners.

As the alarm spread to the south, reinforcements continued to arrive in the village. By midnight, 80 men from Northampton and Springfield had arrived, and men from Connecticut swelled the force to 250 by the end of the next day. After debating over what action to take, it was decided that the difficulties of pursuit were not worth the risks. Leaving a strong garrison in the village, most of the militia returned to their homes.

The raiders destroyed 17 of the village’s 41 homes, and looted many of the others. They killed 44 residents of Deerfield: 10 men, 9 women, and 25 children, five garrison soldiers, and seven Hadley men. Of those who died inside the village, 15 died of fire-related causes; most of the rest were killed by edged or blunt weapons. They took 109 villagers captives; this represented 40 per cent of the village population. They also took captive three Frenchmen who had been living among the villagers. The raiders also suffered losses, although reports vary. New France’s Governor-General Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil reported the expedition only lost 11 men, and 22 were wounded, including Hertel de Rouville and one of his brothers. John Williams heard from French soldiers during his captivity that more than 40 French and Indian soldiers were lost; Haefeli and Sweeney believe the lower French figures are more credible, especially when compared to casualties incurred in other raids.

The raid has been immortalized as a part of the early American frontier story, principally due to the account of one of its captives, the Rev. John Williams. He and his family were forced to make the long overland journey to Canada, and his daughter Eunice was adopted by a Mohawk family; she took up their ways. Williams’ account, The Redeemed Captive, was published in 1707 and was widely popular in the colonies.

She liked to go to Deacon French’s, who lived on what is now the site of the second church parsonage. The Deacon was the blacksmith of the village, and his shop stood a few rods west of his house. Eunice would stand hours watching him, as he beat into shape the plough-shares, that had been bent by [p.132] the stumps in the newly cleared lands. As the sparks flew up from the flaming forge, she thought of the verse in the Bible, “Man is born unto trouble as the sparks fly upward,” and wondered what it meant. Too soon, alas, she learned.

For the 109 English captives, the raid was only the beginning of their troubles. The raiders still had to return to Canada, a 300 miles journey, in the middle of winter. Many of the captives were ill-prepared for this, and the raiders were themselves short on provisions. The raiders consequently engaged in a brutal yet common practice: captives were slain when it was clear they would be unable to keep up. Only 89 of the captives survived the ordeal; most of those who either died of exposure or were slain en route were women and children. Thomas’ wife Mary Caitin French was killed on the trip on 9 March 1703/04.

In the first few days several of the captives escaped. Hertel de Rouville instructed Reverend Williams to inform the others that recaptured escapees would be tortured; there were no further escapes. (The threat was not an empty one — it was known to have happened on other raids.) The French leader’s troubles were not only with his captives. The Indians had some disagreements amongst themselves concerning the disposition of the captives, which at times threatened to come to blows. A council held on the third day resolved these disagreements sufficiently that the trek could continue.

The raid failed to accomplish one of Governor Vaudreuil’s objectives: to instill fear in the English colonists. They instead became angry, and calls went out from the governors of the northern colonies for action against the French colonies. Governor Dudley wrote that “the destruction of Quebeck and Port Royal would put all the Navall stores into Her Majesty’s hands, and forever make an end of an Indian War”, the frontier between Deerfield and Wells was fortified by upwards of 2,000 men, and the bounty for Indian scalps was more than doubled, from £40 to £100. Dudley also promptly organized a retaliatory raid against Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia). In the summer of 1704, New Englanders under the leadership of Benjamin Church raided Acadian villages at Pentagouet (present-day Castine, Maine), Passamaquoddy Bay (present-day St. Stephen, New Brunswick), Grand Pré, Pisiquid, and Beaubassin (all in present-day Nova Scotia). Church’s instructions included the taking of prisoners to exchange for those taken at Deerfield, and specifically forbade him to attack the fortified capital, Port Royal.

Deerfield and other communities collected funds to ransom the captives, and French authorities and colonists also worked to extricate the captives from their Indian masters. Within a year’s time, most of the captives were in French hands, a product of frontier commerce in humans that was fairly common at the time. The French and Indians also engaged in efforts to convert their captives to Roman Catholicism, with modest success. Some of the younger captives, however, were not ransomed, and were adopted into the tribes. Such was the case with Williams’ daughter Eunice, who was eight years old when captured. She became thoroughly assimilated, and married a Mohawk man when she was 16. Other captives also remained by choice in Canadian and Native communities such as Kahnawake for the rest of their lives.

Two of Thomas’ daughters who stayed in Canada married and had large families. The third daughter assimilated into the Indians at Kahnawake. One great-grandson was Archbishop Octave Plessis, who was the ranking churchman to champion the Catholic viewpoint to the British government in the first decades of the 1800’s. That the Church survived is largely due to his efforts.

Negotiations for the release and exchange of captives began in late 1704, and continued until late 1706. They became entangled in unrelated issues (like the English capture of French privateer Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste), and larger concerns, including the possibility of a wider-ranging treaty of neutrality between the French and English colonies. Mediated in part by Deerfield residents John Sheldon and John Wells, some captives were returned to Boston in August 1706. Governor Dudley, who needed the successful return of the captives for political reason, then released the French captives, including Baptiste; the remaining captives that had chosen to return were back in Boston by November 1706.

Thomas French and his children Mary and Thomas Jr. were brought back to Deerfield in 1706 by Ensign John Sheldon, in his second expedition to Canada for the redemption of the captives. An interesting evidence of the proneness of Deerfield maidens to versifying, exists in a poem said to have been written by Mary French to a younger sister during their captivity, in the fear last the latter might become a Romanist (Catholic).

Soon after his return, Thomas French was made Deacon of the church in Deerfield in place of Deacon David Hoyt, who had died of starvation at Coos on the march to Canada. In 1709, Deacon French married the widow of Benoni Stebbins. He died in 1733 at the age of seventy six, respected and regretted as an honest and usefu1:man and a pillar of the church and state.

John Williams wrote a captivity narrative about his experience, which was published in 1707. The work was widely distributed in the 18th and 19th centuries, and continues to be published today. Williams’ work was one of the reasons this raid, unlike others of the time, was remembered and became an element in the American frontier story. In the 19th century the raid began to be termed a massacre (where previous accounts had used words like “destruction” and “sack”, emphasizing the physical destruction); this terminology was still in use in mid-20th century Deerfield. A portion of the original village of Deerfield has been preserved as a living history museum; among its relics is a door bearing tomahawk marks from the 1704 raid. The raid is commemorated there in leap years.

An 1875 legend recounts the attack as an attempt by the French to regain a bell, supposedly destined for Quebec, but pirated and sold to Deerfield. The legend continues that this was a “historical fact known to almost all school children.” However, the story, which is a common Kahnawake tale, was refuted as early as 1882.

4. Mary French

Mary’s husband Samuel Stebbins was born 21 Jan 1659 in Northampton, Hampshire, Mass. His parents were John Stebbins and Abigail Bartlett. After the divorce, he married 14 Mar 1692/93 in Rhode Island to Sarah Williams (b. 1660 in Rhode Island – d. 26 Jan 1697). Samuel died 3 Sep 1732 in Coldspring, Hampshire, Mass.

Mary and Samuel Stebbins were divorced 27 Dec 1692 after 15 years of marriage; HDF sources: Stebbins gene., pg. 115; Parsons gene., 1/684

Samuel Stebbins was divorced by his first wife Mary French for infidelity which included his siring of several children by Sarah Williams. The decree was rendered 27 DEC 1692 and Samuel m 12 MAR 1692/3 Sarah Williams in Rhode Island. The subject of the article is apparently the son of Samuel by another extra-marital affair with Ruth Baker who subsequently married Ebenezer Alford.

7. Hannah French

Hannah’s husband Francis Keet was born 1665 in Rehobeth, Essex, Mass. His parents were Francis Keet and [__?__]. Francis died 9 May 1751 in Sunderland, Franklin, Mass.

8. Jonathan French

Jonathan’s wife Sarah Warner was born 28 May 1668 in Hadley, Hampshire, Mass. Her parents were Isaac Warner and Sarah Boltwood. Sarah died in 1724 in Hatfield, Hampshire, Mass

9. Elizabeth French

Elizabeth’s husband Samuel Pomeroy was born 29 May 1669 in Northampton, Mass. His parents were Caleb Pomerory and Hepzibah Baker. After Elizabeth died, he married to Joanna Root (b. 5 Nov 1681 in Northampton, Mass. – d. 20 Jan 1713 in Northampton, Mass.) After Joanna died, he married 1715 in Northampton, Hampshire, Mass. to Elizabeth Strickland (b. 29 Jan 1685 in Simsbury, Hartford, CT – d. Southampton, Hampshire, Mass.) Samuel died 29 Oct 1748 in Northampton, Hampshire, Mass

Samuel was a farmer and schoolteacher.

Sources:

The history of Peter Parker and Sarah Ruggles of Roxbury, Mass. and their ancestors and descendants … By John William Linzee 1918

The redeemed captive returning to Zion: or, The captivity and deliverance of Rev. John Williams of Deerfield 1704 Google EBook

http://www.1704.deerfield.history.museum/home.do

http://www.genealogyofnewengland.com/b_f.htm

http://aleph0.clarku.edu/~djoyce/gen/report/rr_idx/idx080.html#FRENCH

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~villandra/MomP/1925.html

Pingback: John French | Miner Descent

Pingback: John Kingsley | Miner Descent

Pingback: Origins | Miner Descent

Pingback: Untimely Deaths | Miner Descent

Pingback: Daniel Bradley | Miner Descent

Pingback: Twins | Miner Descent

Pingback: Raid on Deerfield – 1704 | Miner Descent

When I am very little,my grandfather Roy (born Canada immigrated USA) is teaching me about the garden and how to catch ‘squab’. While we wait for the bird to come so I can pull the string to the cage, He solemnly tells me about a” long walk in the woods in the winter walking walking walking and trying to keep the baby warm”.

It seems important to him that I know about this. I wonder why they do not go into the house to get warm.

Years later, as I sit in a genealogy library and a librarian looks at me and sadly says..”oh sorry you can’t go any further there was a raid on a town.. Deerfield… I flash back to my time with my grandfather and I tell the librarian I live in Northampton, next to Deerfield. I jump up and zoom back from Manchester.

I know what Pepe was talking about..after 40 years!

And I found his line. He was taking about his fourth great grandmother, my sixth great grandmother is Martha-Marguerite French, daughter of Deacon Thomas French and Marguerite Catlin of Deerfield. They gave her to the nuns, the nuns gave her to a foster home, of Roys. She married Jacques Roy, Sieur de St Laurent.

Needs checking. John French who married Hannah Palmer, was son of Joseph French (John and Joanna Syday)and Experience Foster. I descend from their son Israel and his wife, Mary Darby.