George CORLISS (1617 – 1686) was Alex’s 9th Great Grandfather; one of 1,024 in this generation of the Miller line.

George Corliss was born about 1617 in Exeter, Devonshire, England. He married Joanna DAVIS 26 Oct 1645 in Haverhill, Mass. George died 19 Oct 1686 in Haverhill. It is a fact worthy of note, that George Corliss, his son, John, and his grandson, John, all died on the same farm, and each one when sitting in the same chair.

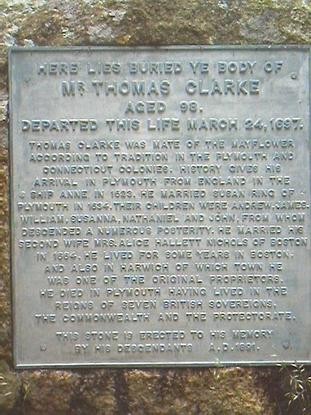

George Corliss – Coat of Arms

Joanna Davis was born about 1624 in Marlborough, Wiltshire, England. Her parents were Thomas DAVIS and Christian COFFIN. She emigrated with her parents on April 05, 1635 on the ship “James” After George died, she married James Ordway on 4 Oct 1687 in Haverhill. Joanna died 12 Jan 192/93 in Haverhill.

Children of George and Joanna

|

Name |

Born |

Married |

Departed |

| 1. |

Mary Corliss |

8 Sep 1646 Haverhill |

William Neff

23 Jan 1664/65 Haverhill |

22 Oct 1722 Haverhill |

| 2. |

John Corliss |

4 Mar 1647/48

Haverhill |

Mary Wilford

17 Dec 1684 Haverhill |

17 Feb 1697/98

Haverhill |

| 3. |

Joanna CORLISS |

28 Apr 1650 in Haverhill |

Joseph HUTCHINS

29 Dec 1669 in Haverhill |

29 Oct 1734 in Haverhill |

| 4. |

Martha Corliss |

2 Jan 1652/53 Haverhill |

Samuel Ladd

1 Dec 1674 Haverhil |

22 Feb 1698

Norwich, New London, Connecticut |

| 5. |

Deborah Corliss |

6 Jun 1655 Haverhill |

Thomas Eastman

20 Jan 1678/79

.

Thomas Kingsbury

29 Jun 1691 Haverhill, Essex, Mass |

22 Oct 1722 Haverhill |

| 6. |

Ann Corliss |

8 Nov 1657 Haverhill |

John Robie

1 Nov 1677 Haverhill |

1 Jun 1691 Haverhill |

| 7. |

Huldah Corliss |

18 Nov 1661 Haverhill |

Samuel Kingsbury

5 Nov 1679 Haverhill |

26 Sep 1720, Haverhill, Essex, Mass |

| 8. |

Sarah Corliss |

23 Feb 1663/64

Haverhill |

Joseph Ayres

24 Nov 1686 Haverhil |

1753

Franklin, New London, CT |

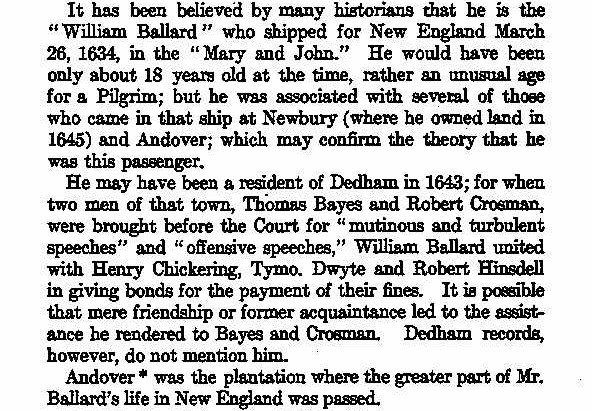

Google books: Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of the State of Massachusetts By William Richard Cutter, William Frederick Adams; Published by Lewis Historical Pub. Co., 1910 Item notes: v.2; Corliss pages 770-772; Original from Harvard University; Digitized Jan 31, 2008

“(I) George Corliss, first American representative

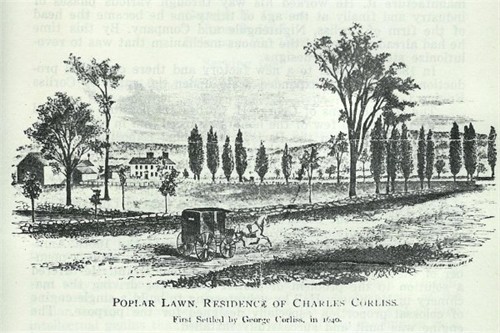

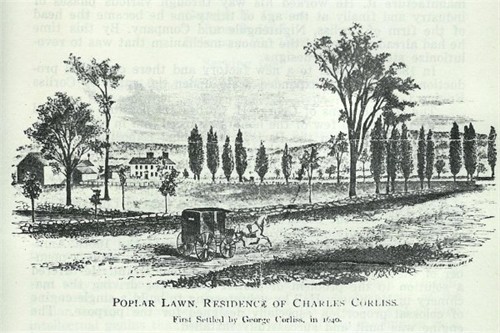

of this ancient family, was born in the county of Devonshire, England, about 1617, and came to this country in 1639, settling at Newbury, Massachusetts. The next year he moved to the neighboring town of Haverhill, where he lived nearly half a century, or until his death in 1686. The original tract of land on which he settled in 1640 and on which he built a log house in 1647, was in what is now known as the West Parish. The farm itself is called “Poplar Lawn,” and has never been out of the possession of his direct descendants.

In some of the old records the name of Thomas Corliss, of Devonshire, England, appears as the father of George Corliss ; but whether this refers to the American emigrant is not certainly known.

George Corliss appears to have been an enterprising and industrious citizen, one well qualified to take part in the settlement of a new town. At his death, October 19, 1686, he left a large property, being possessed of most of the land on both sides of the old “Spicket Path” for a distance of more than three miles. It is a fact worthy of note, that George Corliss, his son, John, and his grandson, John (2), all died on the same farm, and each one when sitting in the same chair.

The name of George Corliss appears on the list of freemen of Haverhill in 1645, and March 26, 1650, he was chosen constable. He served as selectman in 1648-53-57-70-79.

On October 26, 1645, at Haverhill, Massachusetts, George Corliss was united in marriage to Joanna Davis. There is evidence to show that she was either sister or daughter of Thomas Davis, a sawyer, of Marlborough, England, who came over in the “James and William,” in April, 1635. The Corliss marriage was the second in town, and there is a tradition in the family that at the time it occurred the bridegroom was possessed of a pair of silk breeches of such generous proportions that his wife afterward converted them into a gown for herself. There is no further record of Joanna Corliss after the settlement of her husband’s estate, unless she contracted a second marriage. The county records show that on October 4, 1687 “Johannah Corley” married James Ordway, at Newbury, Massachusetts.

Children of George and Joanna (Davis) Corliss:

Mary, born September 6, 1646; John, whose sketch follows; Joanna, born April 28, 1650; Martha, June 2, 1652; Deborah, June 6, 1655 ; Ann, November 8, 1657; Huldah, November 18, 1661 ; Sarah, February 23, 1663. According to the father’s will, the eldest daughter, Mary, married William Neff ; Martha married Samuel Ladd ; Deborah married Thomas Eastman ; Huldah married Samuel Kingsbury. The youngest daughter is mentioned in the will as “Sarah Corley.” “

George Corliss owned a farm called “Poplar Lawn”

Residence of Charles Corliss

1639 – Settled in Newbury, MA, at which date he gave his age as 22 yrs.

1645 – Was made Freeman

1650 – Elected Constable of Haverhill, MA

Elected Town Selectman repeatedly

Children

1. Mary Corliss

Mary’s husband William Neff was born about 1642 in Newbury, Essex, Mas. His parents were William Nesse and Jerusha West. William died 7 Feb 1689 in Pemaquid, Maine.

On 15 Mar 1697 Mary Neff was nursing Hannah Dustin who had given birth the week before. They taken prisoner by the Indians in an attack on Haverhill and carried towards Canada.

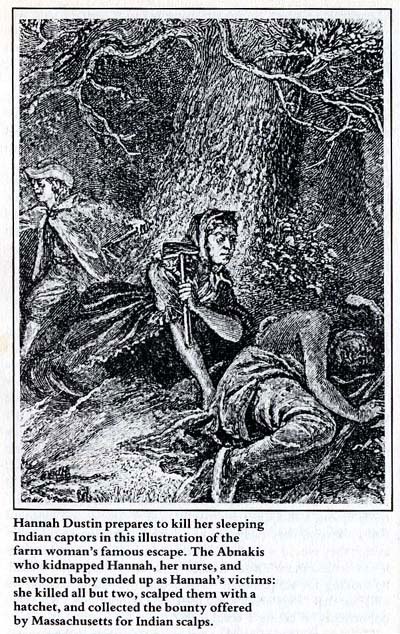

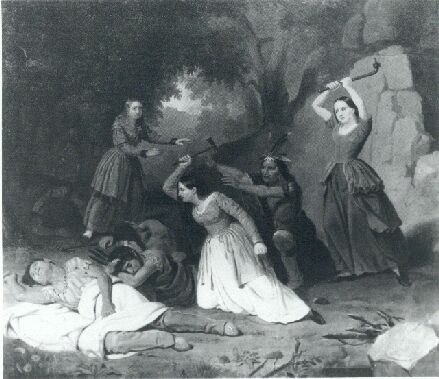

Hannah Duston (1657 – 1736) was a colonial Massachusetts Puritan woman who escaped Native American captivity by leading her fellow captives in scalping their captors at night. Duston is the first woman honored in the United States with a statue.

Today, Hannah Duston’s actions are controversial, with some calling her a hero, but others calling her a villain, and some Abenaki leaders saying her legend is racist and glorifies violence. As early as the 19th Century, Hannah’s legal argument had lost its Old Testament authority and came to be interpreted, or misinterpreted, as a justification for vengeance. See my post Hannah Dustin – Hero or Cold Blooded Killer for details on how the telling of the story has evolved.

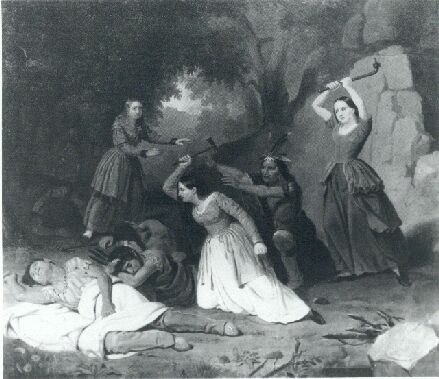

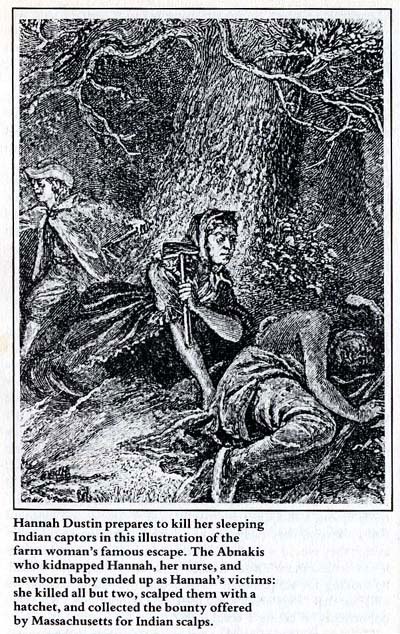

Hannah Dustin and Mary Neff take justice into their own hands

Twenty-seven persons were slaughtered, (fifteen of them children) and thirteen captured. The following is a list of the killed:-John Keezar, his father, and son, George; John Kimball and his mother, Hannah ; Sarah Eastman [Daughter of Deborah Corliss and grand daughter of George CORLISS; Thomas Eaton ; Thomas Emerson, his wife, Elizabeth, and two children, Timothy and Sarah ; Daniel BRADLEY’s son Daniel Bradley, his wife, Hannah (she was also Stephen DOW’s daughter), and two children, Mary and Hannah ; Martha Dow, daughter of Stephen DOW; Joseph, Martha, and Sarah Bradley, children of Joseph Bradley, another son of Daniel BRADLEY ; Thomas and Mehitable Kingsbury[Children of Deborah Corliss and grand daughter of George CORLISS] ; Thomas Wood and his daughter, Susannah ; John Woodman and his daughter, Susannah; Zechariah White ; and Martha, the infant daughter of Mr. Duston.” Hannah Dustin’s nurse Mary Neff, daughter of our ancestor GEORGE CORLISS, was carried away and helped in the escape by hatcheting her captors. Another captive who later wrote about the adventure and was kidnapped a second time ten years later was Hannah Heath Bradley, wife of Daniel BRADLEY’s son Joseph, daughter of John Heath and Sarah Partridge, and grand daughter of our ancestor Bartholomew HEATH.

15 March 1697 – After the attack on Duston’s house, the Indians dispersed themselves in small parties, and attacked the houses in the vicinity. Nine houses were plundered and reduced to ashes on that eventful day, and in every case their owners were slain while defending them.

The ordeal of Hannah Dustin is among the most horrific in New England colonial history. According to an early account by Cotton Mather, Dustin was captured on March 15, 1697 by a group of about 20 Indians and pulled from her bed one week after giving birth to her eighth child. Her husband managed to get the others to safety. The infant was killed when a member of the raiding party smashed it against a tree. Dustin and small group of hostages were marched about 60 miles from her home in Haverhill, MA to an island in the Merrimack River near Concord. Enlisting the help of others, including her nurse and an English boy previously captured, the group managed, amazingly, to kill 10 of their captors. Dustin sold the scalps to the local province for 50 pounds in reparation. A monument to Dustin can be seen in Haverhill and the site of her escape with companions Mary Neff and Samuel Lennardeen can be seen in Boscowen, NH. The Hannah Dustin Trail in Pennacook leads to another monument on the island on the Contoocook River.

Hannah Dustin Statue Penacook New Hampshire

Chase, History of Haverhill, pg. 216

Summer 1707 – “Sometime in the summer of this year, a small party of Indians again visited the garrison of Joseph Bradley; and it is said that he, his wife and children, and a hired man, were the only persons in it at the time. It was in the night, the moon shone brightly, and they could be easily seen, silently and cautiously approaching. Mr. Bradley armed himself, his wife and man, each with a gun, and such of his children as could shoulder one. Mrs. Bradley, supposing that they had come purposely for her, told her husband that she had rather be killed than be again taken. The Indians rushed upon the garrison, and endeavored to beat down the door. They succeeded in pushing it partly open, and when one of the Indians began to crowd himself through the opening, Mrs. Bradley fired her gun and shot him dead. The rest of the party, seeing their companion fall, desisted from their purpose, and hastily retreated.”

“Among the things which call far mention in our history for 1738, is the petition of Hannah [Heath] Bradley, of this town, to the General Court, asking for a grant of land, in consideration of her former sufferings among the Indians, and ” present low circumstances.” In answer to her petition, that honorable body granted her two hundred and fifty acres of land, which was laid out May 29, 1739, by Richard Hazzen, Surveyor. (Son of our ancestor Edward HAZEN Sr.) It was located in Methuen, in two lots, -the first, containing one hundred and sixty acres, bordering on the west line of Haverhill ; the other, containing ninety acres, bordering on the east line of Dracut

Mrs. Bradley’s good success in appealing to the generosity of the General Court, seems to have stimulated Joseph Neff, a son of Mary Neff, to make a similar request. He shortly after petitioned that body for a grant of land, in consideration of his mother’s services in assisting Hannah Duston in killing “divers Indians.” Neff declares in his petition, that his mother was ” kept a prisoner for a considerable time,” and ” in their return home past thro the utmost hazard of their lives and Suffered distressing want being almost Starved before they Could Return to their dwellings.”

Accompanying Neff’s petition, was the following deposition of Hannah Bradley, which well deserves a place in our pages, for its historical interest. The document proves that Mrs. Bradley was taken prisoner at the same time with Mrs. Duston, and travelled with her as far as Pennacook:

Deposition was sworn to before Joshua Bayley, of Haverhill, June 28th, 1739.”

” The deposition of the Widow Hannah Bradly of Haverhill of full age who testifieth & saith that about forty years past the said Hannah together with the widow Mary Neff were taken prisoners by the Indians & carried together into captivity, & above penny cook the Deponent was by the Indians forced to travel farther than the rest of the Captives, and the next night but one there came to us one Squaw who said that Hannah Dustan and the aforesaid Mary Neff assisted in killing the Indians of her wigwam except herself and a boy, herself escaping very narrowly, chewing to myself & others seven wounds as she said with a Hatched on her head which wounds were given her when the rest were killed, and further saith not.

her

Hannah X Bradly.”

mark

Hannah Heath Bradley’s (Joseph Bradley’s wife) desposition is a little confusing because she was taken captive in 1707 and Mary Neff was taken captive ten years earlier in 1697. Either Hannah was taken captive twice or she used poetic license in her deposition connecting herself with the more famous Dustin case. Two other Hannah Bradleys were killed in the 1697 attack, Daniel Bradley Jr’s wife and daughter.

Statue of Hannah Dustin in Haverhill, Mass

Detailed Account

Here’s a more detailed account of Hannah and Mary from The Duston / Dustin Family, Thomas and Elizabeth (Wheeler) Duston and their descendants. and The Story of Hannah Duston Published by the Duston-Dustin Family Association, H. D. Kilgore Historian Haverhill Tercentenary – June, 1940. I’ve kept most of the 19th Century language, only removing a few breathless adverbs, opinionated adjectives and changing some pejorative nouns.

On March 14, 1697, Thomas and Hannah Duston lived in a house on the west side of the Sawmill River in the town of Haverhill. This house was located near the great Duston Boulder and on the opposite side of Monument Street.

Their twenty years of married life had brought them material prosperity, and of the twelve children who had been born to them during this period, eight were living. Thomas, who was quite a remarkable man, – a bricklayer and farmer, who, according to tradition, even wrote his own almanacs, and wrote them on rainy days, – was beginning to have time to devote to town affairs, and had just completed a term as Constable for the “west end” of the town of Haverhill.

He was at this time engaged in the construction with bricks from his own brickyard of a new brick house about a half mile to the northwest of his home to provide for the needs of his still growing family, for Baby Martha had just made her appearance on March 9.

Under the care of Mrs. Mary Neff, (daughter of George CORLISS and widow of William Neff) both mother and child were doing well, the rest of the family were in good health, his material affairs were prospering, and it was undoubtedly with a rather contented feeling that Thomas, to say nothing of his family, retired to rest on the eve of that fateful March 15, 1697, little knowing what horrors the morrow was to bring.

Of course, there was always the fear of Indians. However, since the capture in August of the preceding year, of Jonathan Haynes and his four children while picking peas in a field at Bradley’s Mills, near Haverhill, nothing had happened, and apprehensions of any further attacks were gradually being lulled. Besides, less than a mile on Pecker’s Hill, was the garrison of Onesiphorus Marsh, one of six established by the town containing a small body of soldiers. It was believed that there was little ground for uneasiness.

But this was only a false security. Count Frontenac, the Colonial Governor of Canada, was using every means at his disposal to incite the Indians against the English as part of his campaign to win the New World for the French King. The latter, due to the need for troops in Europe, where the war known as King William’s War was going on, was unable to send many to help Frontenac. So, with propaganda and gifts, the French Governor had allied the tribes to the French cause and bounties had been set on English scalps and prisoners. Every roving band of Indians was determined to get its share of these, and even now, such a band was in the woods near Haverhill, preparing for a lightning raid on the town with the first light of dawn. The squaws and children were left in the forest to guard their possessions, while the Indian warriors moved stealthily towards the house of Thomas and Hannah Duston, the first attacked. [The Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 ended the war between the two colonial powers, reverting the colonial borders to the status quo ante bellum. The peace did not last long, and within five years, the colonies were embroiled in the next phase of the French and Indian Wars, Queen Anne’s War.]

Early the next morning, Thomas, at work near the house, suddenly spied the approaching Indians. Instantly seizing his gun he mounted his horse and raced for the house, shouting a warning which started the children towards the garrison, while he dashed into the house hoping to save his wife and the baby. Quickly seeing that he was too late, and doubtless urged by Hannah, he rode after the children, resolving to escape with at least one. On overtaking them, finding it impossible to choose between them, he resolved, if possible, to save them all. A few of the Indians pursued the little band of fugitives, firing at them from behind trees and boulders, but Thomas, dismounting and guarding the rear, held back the savages from behind his horse by threatening to shoot whenever one of them exposed himself. Had he discharged his gun they would have closed in at once, for reloading took considerable time. He was successful in his attempt, and all reached the garrison safely, the older children hurrying the younger along, probably carrying them at times. This was probably the garrison of Onesiphorus March on Pecker’s Hill.

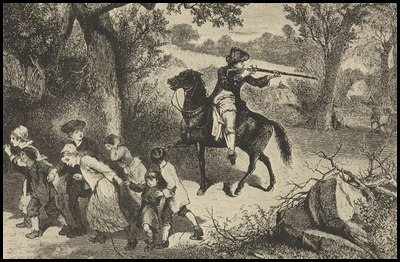

Escape of Thomas Dustin & children. Source: Some Indian Stories of Early New England, 1922

Meanwhile a fearful scene was being enacted in the home. Mrs. Neff, trying to escape with the baby, was easily captured. Invading the house, the Indians forced Hannah to rise and dress herself. Sitting despairingly in the chimney, she watched them rifle the house of all they could carry away, and was then dragged outside while they fired the house, in her haste forgetting one shoe. A few of the Indians then dragged Hannah and Mrs. Neff, who carried the baby, towards the woods, while the rest of the band, rejoined by those who had been pursing Thomas and the children, attacked other houses in the village, killing twenty-seven and capturing thirteen of the inhabitants.

Finding that carrying the baby was making it hard for Mrs. Neff to keep up, one of the Indians seized it from her, and before its mother’s horrified eyes dashed out its brains against an apple tree. The Indians, forcing the two women to their utmost pace, at last reached the woods and jointed the squaws and children who had been left behind the night before. Here they were soon after joined by the rest of the group with their plunder and other captives.

Fearing a prompt pursuit, the Indians immediately set out for Canada with their booty. Some of the weaker captives were knocked on the head and scalped, but in spite of her condition, poorly clad and partly shod, Hannah, doubtless assisted by Mrs. Neff, managed to keep up, and by her own account marched that day “about a dozen miles”, a remarkable feat. During the next few days they traveled about a hundred miles through the unbroken wilderness, over rough trails, in places still covered with the winter’s snow, sometimes deep with mud, and across icy brooks, while rocks tore their half shod feet and their poorly clad bodies suffered from the cold – a terrible journey.

Near the junction of the Contoocook and Merrimack rivers, twelve of the Indians, two men, three women, and seven children, taking with them Hannah, Mrs. Neff and a boy of fourteen years, Samuel Lennardson (who had been taken prisoner near Worcester about eighteen months before), left the main party and proceeded toward what is now Dustin Island, situated where the two rivers unite, near the present town of Penacook, N.H. This island was the home of the Indian who claimed the women as his captives, and here it was planned to rest for a while before continuing on the long journey to Canada.

This Indian family had been converted by the French priests at some time in the past, and was accustomed to have prayers three times a day, – in the morning, at noon and at evening, – and ordinarily would not let their children eat or sleep without first saying their prayers. Hannah’s master, who had lived in the family of Rev. Mr. Rowlandson of Lancaster some years before told her that “when he prayed the English way he thought that it was good, but now he found the French way better.” They tried, however, to prevent the two women from praying, but without success, for as they were engaged on the tasks set by their master, they often found opportunities. Their Indian master would sometimes say to them when he saw them dejected, “What need you trouble yourself? If your God will have you delivered, you shall be so!”

[Mary (White) Rowlandson (c. 1637 – Jan 1711) was a colonial American woman who was captured by Indians during King Philip’s War and endured eleven weeks of captivity before being ransomed. After her release, she wrote a book about her experience, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, which is considered a seminal work in the American literary genre of captivity narratives.

During the long journey Hannah was secretly planning to escape at the first opportunity, spurred by the tales with which the Indians had entertained the captives on the march, picturing how they would be treated after arriving in Canada, stripped and made to “run the gauntlet”; jeered at and beaten and made targets for the young Indians’ tomahawks; how many of the English prisoners had fainted under these tortures; and how they were often sold as slaves to the French. These stories, added to her desire for revenging the death of her baby and the cruel treatment of their captors while on the march, made this desire stronger. When she learned where they were going, a plan took definite shape in her mind, and was secretly communicated to Mrs. Neff and Samuel Lennardson.

Samuel, who was growing tired of living with the Indians, and in whom a longing for home had been stirred by the presence of the two women, the next day casually asked his master, Bampico, how he had killed the English. “Strike ‘em dere,” said Bampico, touching his temple, and then proceeded to show the boy how to take a scalp. This information was communicated to the women, and they quickly agreed on the details of the plan. They arrived at the island some time before March 30, 1697.

After reaching the island, the Indians grew careless. The river was in flood. Samuel was considered one of the family, and the two women were considered too worn out to attempt escape, so not watch was set that night and the Indians slept soundly. Hannah decided that the time had come.

Shortly after midnight she woke Mrs. Neff and Samuel. Each, armed with a tomahawk, crept silently to a position near the heads of the sleeping Indians – Samuel near Bampico and Hannah near her master. At a signal from Hannah the tomahawks fell, and so swiftly and surely did they perform their work of destruction that ten of the twelve Indians were killed outright, only two – a severely wounded squaw and a boy whom they had intended to take captive – escaped into the woods. According to a deposition of Hannah Bradley in 1739 (History of Haverhill, Chase, pp. 308-309),

“above penny cook the Deponent was forced to travel farther than the rest of the captives, and the next night but one there came to us one Squaw who said that Hannah Dustan and the aforesaid Mary Neff assisted in killing the Indians of her wigwam except herself and a boy, herself escaping very narrowly, shewing to myself & others seven wounds as she said with a Hatched on her head which wounds were given her when the rest were killed.”

Hastily piling food and weapons into a canoe, including the gun of Hannah’s late master and the tomahawk with which she had killed him, they scuttled the rest of the canoes and set out down the Merrimack River.

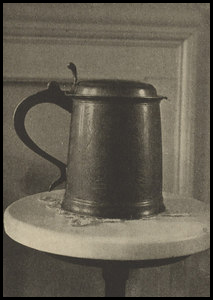

Original Gun taken by Hannah Dustin

Suddenly realizing that without proof their story would seem incredible, Hannah ordered a return to the island, where they scalped their victims, wrapping the trophies in cloth which had been cut from Hannah’s loom at the time of the capture, and again set out down the river, each taking a turn at guiding the frail craft while the others slept.

Hannah Dustin and Mary Neff make their escape

Thus, traveling by night and hiding by day, they finally reached the home of John Lovewell in old Dunstable, now a part of Nashua, N.H. Here they spent the night, and a monument was erected here in 1902, commemorating the event. The following morning the journey was resumed and the weary voyagers at last beached their canoe at Bradley’s Cove, where Creek Brook flows into the Merrimack. Continuing their journey on foot, they at last reached Haverhill in safety. Their reunion with loved ones who had given them up for lost can better be imagined than described.

Hannah Dustin Detail

Thomas took his wife and the others to the new house which he had been building at the time of the massacre, and which was now completed. Here for some days they rested. The fear induced by the massacre caused Haverhill to at once establish several new garrison houses. One of these was the brick house which Thomas was building for his family at the time of the massacre. This was ordered completed, and though the clay pits were not far from the home, a guard of soldiers was placed over those who brought clay to the house. The order establishing Thomas Duston’s house as a garrison was dated April 5, 1697. He was appointed master of the garrison and assigned Josiah HEATH, Sen., Josiah Heath Jun., Joseph Bradley, John Heath, Joseph Kingsbury, and Thomas Kingsbury as a guard.

Dustin Garrison

In 1694 a bounty of fifty pounds had been placed on Indian scalps, reduced to twenty-five pounds in 1695, and revoked completely on Dec. 16, 1696.

Hannah had risked precious time to gain those scalps. The explanation sometimes given later, that her story would not be believed without evidence, is patently false. If her credibility were the only issue at stake, sooner or later there would be corroborative accounts. Actually, Hannah Bradley, another Haverhill woman, was a captive in the camp where the wounded squaw sought refuge. But to collect a scalp bounty Hannah needed to produce the scalps.

Thomas Duston believed that the act of the two women and the boy had been of great value in destroying enemies of the colony, who had been murdering women and children, and decided that the bounty should be claimed. So he took the two women and the boy to Boston, where they arrived with the trophies on April 21, 1697.

Here he filed a petition to the Governor and Council, which was read on June 8, 1697 in the House

To the Right Honorable the Lieut Governor & the Great & General assembly of the Province of Massachusetts Bay now convened in BostonThe Humble Petition of Thomas Durstan of Haverhill Sheweth That the wife of ye petitioner (with one Mary Neff) hath in her Late captivity among the Barbarous Indians, been disposed & assisted by heaven to do an extraordinary action, in the just slaughter of so many of the Barbarians, as would by the law of the Province which——–a few months ago, have entitled the actors unto considerable recompense from the Publick.

That tho the———-of that good Law————–no claims to any such consideration from the publick, yet your petitioner humbly—————-that the merit of the action still remains the same; & it seems a matter of universal desire thro the whole Province that it should not pass unrecompensed.

And that your petitioner having lost his estate in that calamity wherein his wife was carried into her captivity render him the fitter object for what consideration the public Bounty shall judge proper for what hath been herein done, of some consequence, not only unto the persons more immediately delivered, but also unto the Generall Interest

Wherefore humbly Requesting a favorable Regard on this occasion

Your Petitioner shall pray &c

Thomas Du(r)stun

Despite the missing words its purport is clear. Hannah has performed a service to the community and deserves an appropriate expression of gratitude. It also implies a justification for killing the squaws and children, if any justification were needed when the captives’ safety depended upon several hours head start.

The same day the General Court voted payment of a bounty of twenty-five pounds “unto Thomas Dunston of Haverhill , on behalf of Hannah his wife”, and twelve pounds ten shillings each to Mary Neff and Samuel. This was approved on June 16, 1697, and the order in Council for the payment of the several allowances was passed Dec. 4, 1697. (Chapter 10, Province Laws, Mass. Archives.)

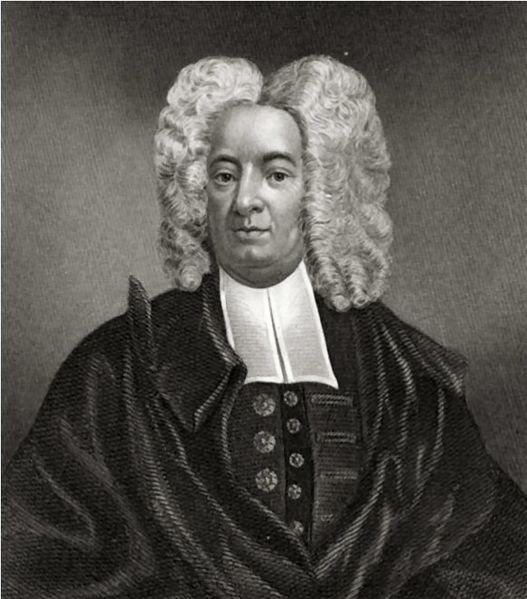

While in Boston Hannah told her story to Rev. Cotton Mather, whose morbid mind was stirred to its depths. He perceived her escape in the nature of a miracle, and his description of it in his “Magnalia Christi Americana” is extraordinary, though in the facts correct and corroborated by the evidence.

In Samuel Sewall’s Diary, Volume 1, pages 452 and 453, we find the following entry on May 12, 1697:

Fourth-day, May12….Hanah Dustin came to see us:….She saith her master, who she kill’d did formerly live with Mr. Roulandson at Lancaster: He told her, that when he pray’d the English way, he thought that was good: but now he found the French way was better. The single man shewed the night before, to Saml Lenarson, how he used to knock Englishmen on the head and take off their Scalps: little thinking that the Captives would make some of their first experiment upon himself. Sam. Lenarson kill’d him.

This remarkable exploit of Hannah Duston, Mary Neff, and Samuel Lennardson was received with amazement throughout the colonies, and Governor Nicholson of Maryland sent her a suitably inscribed silver tankard.

Dustin Tankard, A gift from the Gov. of Maryland to Hannah Dustin in 1697. In possession of the Haverhill Historical Society, Hav. Mass. Source: Some Indian Stories of Early New England, 1922

2. John Corliss

John’s wife Mary Wilford was born 18 Nov 1667 in Rowley, Mass. Her parents were Gilbert Wilford and Mary Dow. Her maternal grandparengts were Thomas DOW and Phebe LATLY. After John died, she married 23 Jan 1702/03 in Haverhill to William Whittaker (b. 21 Dec 1658, Haverhill). Mary died after 1711 in Haverhill.

John served in King Philip’s War, under Lieutenant Benjamin Swett, June 1676, also August 1676 . He owned at least one slave, Celia. In 1798 John’s house was valued at $350. He inherited the farm from his father, George Corliss and lived there all his life.

John Corliss fought in King Philip’s War under Lt. Benjamin Swett in June & August, 1676; took the oath of allegiance, November 28, 1677. From the Essex County Quarterly Courts Records, 4:193: “John Corliss deposed that he heard Joseph Davis send to Pecker to raise the flood gates when the sawmill at Haverhill was lost in the 1668 flood and Ensign James Pecker was charged with responsibility.

Children of John and Mary:

i. John Corliss, Jr., b. 14 Mar 1685/86, Haverhill, Essex, Massachusetts , d. Nov 1766, Haverhill

ii. Mary Corliss, b. 25 Feb 1687/88, Haverhill, Essex , Mass , d. Aft 3 May 1708

iii. Thomas Corliss, b. 2 Mar 1689/90, Haverhill, Essex, Mass , d. 3 Sep 1781, Haverhill

iv. Hannah or Anna Corliss, b. Sep 1691/92, Haverhill, Essex , Mass , d. 8 Sep 1764

v. Timothy Corliss, b. 13 Dec 1693, Haverhill, Essex , Mass , d. 1783, Weare, Hillsborough , New Hampshire; m. 15 Feb 1725/26 in Haverhill to Sarah Hutchins (b. 20 Jun 1701 in Haverhill) Sarah’s parents were John’ Hutchins and Sarah Page. Her grandparents were Joseph HUTCHINS and Joanna CORLISS

vi. Jonathan Corliss, b. 16 Jul 1695, Haverhill, Essex, Massachusetts , d. 22 Mar 1787, Salem, Rockingham, New Hampshire

vii. Mehitable Corliss, b. 5 May 1698, Haverhill, Essex , Massachusetts , d. Jan 1742, Rumford (Concord), Merrimack , New Hampshire

3. Joanna CORLISS (See Joseph HUTCHINS’ page)

4. Martha Corliss

Martha’s husband Samuel Ladd was born 1 Nov 1649 in Haverhill, Essex, Mass. His parents were Daniel Ladd and Ann Moore. Samuel was killed in Indians 22 Feb 1698 in Haverhill, Essex, Mass. According to his son, the Indians didn’t take him captive because “‘he so sour’.” Little did they know the poetic justice of Ladd’s demise and the immoral crimes he had inflicted on Elizabeth Emerson.

History of Haverhill – Jonathan Haynes and Samuel Ladd, who lived in the western part of the town, had started that morning, with their teams, consisting of a yoke of oxen and a horse, each, and accompanied with their eldest sons, Joseph (age 22) and Daniel, to bring home some of their hay, which had been cut and stacked the preceding sumner, in their meadow, in the extreme western part of the town. Whey they were slowly returning, little dreaming of present danger, they suddenly found themselves between two files of Indians, who had concealed themselves in the bushes on each side of their path. There were seven of them on a side. With guns presented and cocked, and the fathers, seeing it was impossible to escape, begged for “quarter.” To this, the Indians twice replied, “boon quarter! boon quarter! (good quarter.) Young Ladd, who did not relish the idea of being quietly taken prisoner, told his father that he would mount the horse, and endeavor to escape. But the old man forbid him to make the attempt, telling him it was better to risk remaining a prisoner. He cut his father’s horse loose, however, and giving him the lash, he started off at full speed, and though repeatedly fired at by the Indians, succeeded in reaching home, and was the means of giving an immediate and general alarm.

Two of the Indians then stepped behind the fathers, and dealt them a heavy blow upon the head. Mr. Haynes who was quite aged, instantly fell, but Ladd did not. Another of the Indians then stepped before the latter, and raised his hatchet as if to strike. Ladd closed his eyes, expecting the blow would fall – but it came not – and when he again opened them, he saw the Indian laughing and mocking at his fears. Another immediately stepped behind him and felled him at a blow.

The Indians, on being asked why they killed the two men, said that they killed Haynes because he was ‘so old he no go with us;’ – meaning that he was too aged and infirm to travel; and that they killed Ladd, who was a fierce, stern looking man, because ‘he so sour’. They then started for Penacook, where they arrived, with the two boys. Young Ladd soon grew weary of his situation, and one night after his Indian master and family had fell asleep, he attempted to escape. He had proceeded but a short distance, when he thought that he should want a hatchet to fell trees to assist him in crossing the streams. He accordingly returned, entered a wigwam near his master’s, where an old squaw lay sick , and took a hatchet The squaw watched his movements, and probably thinking that he intended to kill her, vociferated with all her strength. This awakened the Indians in the wigwam, who instantly arose, re-captured him, and delivered him again to his master, who bound his hands, laid him upon his back, fastened one of his feet to a tree, and in that manner kept him fourteen nights. They then gashed his face with their knives, filled the wounds with powder, and kept him on his back, until it was so indented in the flesh, that it was impossible to extract it. He carried the scars to his grave, and was frequently spoken of his descendants as the ‘marked man.’

After several years, Daniel did escape and returned to Haverhill where he lived until his death in 1751. On Daniels’ return to his home he became heir to his father’s estate and head of the family. He married 17 Nov 1701, Haverhill to Susannah Hartshorne and fathered (children 1702-17: Mary, Susanna, Samuel, Daniel, Ruth, John)

When Daniel returned home his brother Nathaniel resented being under the control of his older brother, so he decided to leave home and make his own way. For about a year he stayed in Haverhill and worked for his uncle in a sawmill he operated. This mill had been built by his grandfather in 1659. While there, he lived with another uncle and was able to save most of his wages.

Nathaniel left Haverhill and spent several years at various places in Connecticut and Massachussetts working at any job available. In 1706, at the age of 22, he had saved enough money to purchase a small farm at Franklin, New London County, Connecticut. In 1707 he met Abigail Bodwell, a daughter of a local farmer, and they married the following year. About this time, Nathaniel purchased a larger farm in Coventry, Tolland CT which was a newer settlement about 15 miles north of Franklin and situated on Lake Waumgumbaug. In Coventry he prospered, added more land, and also took active part in church and civic affairs. He served as Selectman for the town for many years. Also held other public offices.

Nathaniel died at Coventry, Tolland, CT on June 11, 1757 at the age of 73. The records show his wife died on August 7, 1798 and would have been over 100 as they were married in 1708. It is possible that Abigail had passed away earlier and he married a younger woman..

Samuel Ladd was responsible for crimes of his own. He was the father of three children born out of wedlock to Elizabeth Emerson, the last two being twins.

i. Dorothy Emerson, b. 10 April 1686 in Haverhill

ii. Infant Emerson, b. 8 May 1691 in Haverhill, d. 10 May 1691

iii. Infant Emerson, b. 8 May 1691 in Haverhill, d. 10 May 1691

Elizabeth was subsequently hanged in the Boston Commons after having been convicted of killing her twins. There is no evidence that Samuel assumed any responsibility with respect to Elizabeth and the children. Elizabeth was the daughter of Michael Emerson and Hannah Webster. She was born 26 Jan 1665 in Haverhill, and was hanged 8 Jun 1693 in The Boston Common. The Records of the Court of assistants of the Massachusetts Bay, Volume I, has an excellent account of the charges and related information regarding Elezabeth Emerson. The Diary of Cotton Mather also has an extended account.

The Story of Elizabeth Emerson

On June 8, 1693 The Reverend Cotton Mather delivered a sermon before a large crowd in Boston. Mather exhorted the crowd, delivering what he unabashedly referred to as one of his greatest sermons ever. In the crowd sat Elizabeth Emerson, singlewoman of Haverhill. Whether she sat penintently looking downwards or definantly staring into Mather’s eyes we can only imagine. That the sermon was delivered for her benefit is undoubted. The lecture was based upon Job 36:14, “They die in youth and their life is among the unclean.”

The life of Elizabeth Emerson would have been wholly unremarkable were it not for three related events: The first was a severe beating she suffered at the hands of her father when she was a child; the second, the birth of her illegitimate daughter Dorothy; and the third event, the reason for her presence in the meeting hall that June day three hundred years ago, her death by hanging for the crime of infanticide.

Elizabeth was born in the town of Haverhill in what was then the Massachusetts Bay Colony 26 Jan 1664/65. She was the sixth of fifteen children of Michael and Hannah Webster Emerson, and one of only nine to survive infancy.

Michael and Hannah Emerson were among the early settlers of Haverhill, though not founding members of the town. He was variously employed as a contable, a Grand Juryman, a cordwainer, a sealer of leather, and a tax collector. Despite the impressive sound of this list, they were positions which those of greater estate would endeavor to avoid. Michael Emerson’s life, too, would have been wholly unremarkable were it not for the fame of one daughter and the infamy of another.

In 1666, when Elizabeth was but a year old, Michael Emerson chose to move his family closer to town. He decided to settle on Mill Street which was then in the heart of Haverhill. One of his new neighbors, a Mr. White, evidently disliked either Michael, his family, or perhaps both. It was decided by the town that if the Emersons would “go back to the woods,” they would grant him an additional tract of land. Michael seeminly obliged the town and moved two miles from the center, which at the time would indeed have been in “the woods.’ This incident seems innocuous enough and is certainly a unique and expedient way of resolving a neighborly difficulty in an area rich in land. One wonders, though, what it was about the family that so angered Mr. White. Undoubtedly, removal that far from town was not only inconvenient but dangerous. The reason for the removal, unfortunately, is not described by the record, but it certainly must have been compelling.

Michael’s first child, Hannah Emerson Dustin, was born23 Dec 1657. She was destined to become famous in the annals of New England history as the only female Indian captive ever to have slain her captors and escaped, not only with her scalp but with theirs as well. Hannah slew her captors with the help of Mary Corliss Neff [George CORLISS‘ daughter see story above] , and a young boy, Samuel Lennardson. Upon her escape from her captors she realized she had forgotten to take trophies of her exploit. She returned to the scene and took scalps from the ten dead Indians; six children, two women and two men. She and her little party managed to find their way down the Merrimac River, from near present day Concord, New Hampshire, to their home in Haverhill. She became a heroine to white New Englanders frustrated with the long Indian wars.

Violence was inescabable in the lives of early New Englanders. Certain types of violence were unacceptable to community standards, whereas other types were not only accepted but also condoned. Among the types of condoned violence were not only violence toward Indians, but also corporal punishment of children, servants and in some cases wives

Children were often singled out as victims of violence. The poetess Anne Bradstreet once wrote “some children (like sowre land) are of so tough and morose a dispo[si]tion, that the plough of correction must make long furrows upon their back. Surely if so gentle a personage as Anne Bradstreet advocated corporal punishment in the raising of children, then it must have been both widespread and condoned. This very approval on a community-wide basis serves as a counterpoint to the case that was brought before the Quarterly Court of Essex County Massachusetts in May of 1676.

Michael Emerson was brought to court that May day “for cruel and excessive beating of his daughter with a flail swingle and for kicking her, was fined and bound to good behavior.”The daughter in question was Elizabeth In November of the same year the back due portion of his fine was abated because of Emerson’s status as a grand juryman, and he was freed from his bond for good behavior, Corporal punishment in and of itself was not considered a crime, but the excessive beating of a child did deserve punishment. Although Michael’s status as a grand juryman did help to get his fine abated and perhaps influenced his release from the bond for good behavior, it did not prevent his fellow grand jurymen from censuring him for the cruelty of his act. What Elizabeth did to deserve such a beating is unknown. Also, whether this beating was an isolated incident or a pattern of violence in the family can only be guessed, but a court case involving another family member may shed further light.

The case involved Elizabeth’s younger brother Samuel who was apprenticed to a John Simmons. Simmons was brought to court by another of his servants, Thomas Bettis, in March of 1681. Bettis claimed in his deposition that his “master haith this mani yeares beaten me upon small and frivelouse ocasion.” Bettis claimed that Simmons had “brocke my hed twice, strucke me on the hed with a great stick…tied me to a beds foott [and] a table foott” and a long list of other injuries and insults suffered at his master’s hand. He begged the court to be allowed to leave his master. A number of community members deposed that Bettis had, indeed, been beaten excessively and had not been clothed properly. But Samuel Emerson took his masters side in the suit saying, “that he had lived with his master Simmons about four years and Bettis was very rude in the family whenever the master was away, etc.”

Perhaps Samuel’s deposition was a form of self defence. After all, he still had to live with Simmons after the suit was over. But maybe Samuel really did think that Bettis deserved the beatings and that they were not excessive given the situation. If the latter is true, it could indicate that this type of violence was by no means foreign to Samuel Emerson’s upbringing. In any event, Bettis was told to return to his master’s house, and there the record ends.

On April 10, 1686 Elizabeth Emerson gave birth to her first child, an illegitimate daugher named Dorothy. There is some controversy surrounding the father of her first child. Charles Henry Pope in his book The Haverhill Emersons stated unequivocally that the father of little Dorothy was Samuel Ladd of Haverhill. This is the same Samuel Ladd who would later be named as the father of the dead twins. Pope, in what can only be viewed as a noble attempt to salvage the reputation of his ancestress, writes that “whatever else Elizabeth might have been, she was certainly not promiscuous.” But the Records And Files Of The Ipswitch Quarterly Court reflect something quite different.

Michael Emerson accused a neighbor, Timothy Swan, of being the father of Elizabeth’s daughter Dorothy. Timothy Swan’s father, Robert Swan, Sr., vehemently denied the charge. Robert Swan went on record as saying that it was unlikely that Timothy was the father as he “…had charged him not to go into that wicked house and his son had obeyed and furthermore his son could not abide the jade.”

Timothy Swan was not a nice person either. Our ancestor Francis HUTCHINS was arrested on the 19th August 1692 as a result of a witchcraft complaint filed by Timothy Swan, Ann Putnam, Jr., and Mary Walcott. Francis was imprisoned until the 21st December 1692 when she was released on bond posted by her son Joseph HUTCHINS his wife Joanna CORLISS HUTCHINS and Joanna’s brother-in-law Samuel Kingsbury (Huldah Corliss ‘ husband) No trial records were found.

Timothy Swann also accused John PERKINS’ daughter Mary Perkins Bradbury. Witnesses testified that she assumed animal forms; her most unusual metamorphosis was said to have been that of a blue boar. Another allegation was that she cast spells upon ships. Over a hundred of her neighbors and townspeople testified on her behalf, but to no avail and she was found guilty of practicing magic and sentenced to be executed. Through the ongoing efforts of her friends, her execution was delayed. After the witch debacle had passed, she was released. By some accounts she was allowed to escape. Others claim she bribed her jailer. Another account claims that her husband bribed the jailer and took her away to Maine in a horse and cart. They returned to Massachusetts after the witch hysteria had died down. Mary Bradbury died of natural causes in her own bed in 1700..

The phrase “that wicked house” rings down through the centuries. Why was Michael Emerson’s house referred to as “wicked” and why was Timothy forbidden to enter the house? Not that Timothy Swan would have necessarily have had to enter the house in order to be the father of Dorothy. It is possible and even likely that Elizabeth contrived to get pregnant elsewhere. But why the phrase “wicked house”?

Presumably Robert Swan and Michael Emerson were well acquainted with one another. Robert Swan had even sold Michael and his brother Robert Emerson “twenty or thirty acres of land.” They had also voted on the same side in a dispute about moving the meeting house to a different location. The breakdown of the meeting house case is rather interesting as Nathaniel Saltonstall, a very wealthy and respected member of the Haverhill community as well as a member of the Court of Assists, and Robert Emerson, brother to Michael but much wealthier and a member of the church in question. both came down on the opposite side of the argument, favoring building the new meetinghouse on the site of the old one. This would indicate that the proposed location of the new meetinghouse was more convenient to both Michael Emerson’s and ?Robert Swan’s households, i.e. they must have been “neighbors.”

Neighbors or otherwise, Robert Swan threatened to “carry the case to Boston” if his son Timothy was formally accused of being Dorothy Emerson’s father. Nothing ever came of the charges against Timothy and little Dorothy came into the world fatherless.

Elizabeth was 23 years old at the time of Dorothy’s birth. She still resided at her father’s house. Three years previous to Dorothy’s birth Elizabeth had witnessed her sister Mary’s successful marriage to Hugh Matthews of Newbury on August 28, 1683. Hugh and Mary were both sentenced by the Essex County Court in September of 1683 to be “fined or severly whipped” for the crime of fornication before marriage. No offspring of this alleged fornication is mentioned in the records but that they did the deed and subsequently had a successful marriage could not have gone unnoticed by Elizabeth. Perhaps Elizabeth expected the same thing to happen to her upon getting pregnant. And why not? The colonial court records are literally strewn with cases involving fornication before marriage where the parties did, indeed, get married and became respectable members of the community. As we know, for Elizabeth, this would not be her fate.

Elizabeth next appeared in the court records in May of 1691, five years after the birth of Dorothy, when she was arrested and charged with the murder of two bastard infants. On May 7, 1691 Elizabeth gave birth to twins sometime during the night in a trundle bed at the foot of her parents bed. She managed to somehow hide the birth from her parents, conceal the infants for three days in a trunk, sew them up in a bag and bury them in the backyard of the Emerson house.

The Sunday following the birth, while her parents were at church, some concerned citizens of Haverhill who suspected that Elizabeth was pregnant went to the Emerson house to find her. When they arrived at the Emerson home they inquired after Elizabeth’s health which she descibed to them as “not well.” She was read a warrant and told that the women who were present were appointed to examine her.

Elizabeth submitted to this examination without protest. Meanwhile, the men went into the backyard and found the bodies of the two infants sewn up in a bag and buried in a shallow grave.

The discovery of the bodies led to statements being taken by Nathaniel Saltonstall. The depositions of the parties involved were similar. They suspected Elizabeth of being with child and therefore sought her out that Sunday morning with the intent of making inquiry. Elizabeth denied any wrongdoing, stating that she “never murdered any child in my life.” She also said “I never committed a murther that I know of….” But the evidence against her in the form of the infant bodies and the physical examination by the women present, where they discovered Elizabeth to be post partum, was overwhelming.

The following day, May 11th, Elizabeth, Michael and Hannah Emerson were all questioned and a transcript of that exchange is still extant. Elizabeth was asked her husband’s name to which she replied, “I have never [had] one.” She confessed that she did give birth to twins. When asked where they were born she replied, “On the bed at my father’s beds feet….” She stated that she did not call for help during her travail because, “there was nobody near but my Father and Mother and I was afraid to call my mother for fear of killing her.” When asked if she told her father or mother afterwards, she replied, “No, not a word; I was afraid.” Elizabeth was then questioned as to whether either of her parents knew of her pregnancy to which she replied that they did not know of the pregnancy, birth or burial of them.

How could Elizabeth have given birth to twins in the same room her parents were sleeping and kept it a secret from them? The record indicates that her mother did suspect Elizabeth of being pregnant but was told “no” every time she inquired of Elizabeth. Elizabeth’s fear of “killing” her mother denotes a certain amount of love and respect, but what of her statement, “No, not a word; I was afraid”? Elizabeth had, after all, been in this position before. She already had one illegitimate child which her father had unsuccessfully tried to pin on Timothy Swan. Could it be that the treatment she had received from ther father after the incident with Robert Swan, Sr. made her loathe to reveal to him her latest indiscretion? After all, Michael was known to have beaten her severely at least once; perhaps she was afraid of similar treatment if the truth was made known to him. Whatever her reason, it must have been compelling for her to have given birth to twins in complete silence while her parents slept mere inches away.

Michael was also questioned on May 11th regarding his daughter’s crime. According to the transcript, he did not even suspect that Elizabeth was with child, nor did he know of the birth or burial of them. When asked if he knew who the father was, he stated for the first time on the record, that the father of the children was Samuel Ladd.

Samuel Ladd was a resident of Haverhill. He was considerably older than Elizabeth, for he was married to his wife on December 1, 1674 when Elizabeth was 9 years old. At the time of the twins birth Pope gives his age as 42 and Elizabeth’s as 28. Although Samuel Ladd was named as the father of the children a number of times in the court records, he was even said to be the one person who knew of Elizabeth’s pregnancy, he was never questioned about the matter.

Samuel Ladd’s father, Daniel Ladd was on the list of the first settlers of Haverhill in As a 1640 first settler he would have received a considerable estate from the normal course of land distribution. Samuel was referred to as Lieutenant Ladd, high rank in the Colonial militia, and he was paid more than twice the amount of any of the other soldiers who formed the militia company during King Philips War. Thus Samuel Ladd was not only the son of a wealthy founder of the community but an important member of it in his own right. As to the character of Samuel Ladd, a court case in which he was involved may be instructive.

On June 9, 1677 Samuel Ladd “was fined for misdemeanors.” “Frances Thurla, [our ancestor Francis THURLOW] aged about forty-five years, and Ane Thurla, his wife, testified that in the evening after Mr. Longfelow’s vessel was launched, about nine or ten o’clock, and after he and his family were in bed, having shut the door and bolted it, Sameull Lad of Haverhill and Thomas Thurla’s man, Edward Baghott, came to their house. One or both of them went into the leanto where their daughter Sarah lay, and having awakened her urged her to rise and go to her aunt’s, telling her that she was very sick. Whereupon deponent arose and seeing one at the door reproved him for being there, and mistrusting that there was one with his daughter, as he went to light a candle, Samuell Lad leaped out of the house. Sworn in court.”

For this Samuel Ladd was found guilty of a misdemeanor. What was he doing at Frances Thurla’s house after all had retired to bed? Why had he tried to get Sarah to leave the house and go to her aunt’s? And if her aunt were, in fact, sick, why did he not tell Sarah’s parents, as the aunt presumably would have been sister to one of them? Was Samuel Ladd bent upon the seduction of young [age 14 at the time] Sarah Thurla ? At the time of the incident Samuel had been married for three years. Sarah THURLOW [also our ancestor] would later William DANFORTH

This was the man accused of being the father of the dead twins. Why he was never questioned regarding his involvement is unknown. Perhaps it was his relative standing in the community that saved him. He was, after all, the son of a founder and somewhat wealthy himself based upon his position in the community. The Emersons were undoubtedly much poorer. And certainly, the fact that Elizabeth already had one bastard child made her testimony as to the patrimony of the twins suspect.

Samuel Ladd did eventually reap some kind of poetic justice for his part in Elizabeth’s demise. On Feb 22, 1697/98 he was killed during an Indian raid. He left a wife and five (legitimate) children.

Elizabeth’s mother Hannah was the next to be questioned regarding her daughter’s crime. She stated for the record that she suspected her daughter was pregnant but as she was big, she could not tell and Elizabeth would not confess to it. She was then accused of being the one to sew them up in a bag but again she denied any knowledge of it. She too named Samuel Ladd as the father of the children.

The women who were sent to the house to examine Elizabeth also gave testimony at the same time as the Emersons. They testified that one of the children had its navel string twisted about its neck. There was apparently no sign of violence to either of the children but in their opinion one or both of them died “for want or caer att the time of travell..”

With these statements went another intriguing document. In it, Elizabeth confessed that Samuel Ladd was the father of the children and that the “place of his begetting…was at Rob’t Clements inn house.”

Elizabeth also states for the record that Samuel is the only man with whom she had slept, indicating by this that he was not only the father of the dead twins but the father of Dorothy as well, contrary to her father’s assertion that Timothy Swan was the father of Dorothy.

There is no record of Robert Clements running an inn or tavern, though he is listed as one of the founders of the town. It is entirely possible that he was running an unlicensed ordinary as this was not an uncommon practice at the time. Evidently Samuel Ladd and Robert Clements were well acquainted with one another as they were close neighbors. Nathaniel Saltonstall was later to write of the perfidy of tavern houses and could well have been thinking of this case when he wrote it.

Elizabeth was remanded to the custody of the Boston prison on May 13, 1691, accompanied by a letter from Nathaniel Saltonstall. In this letter he writes that he had Elizabeth before him on May 11th and 13th…”upon examination for whore-dom.” He then reiterated the facts of the case as they were known and commanded the prison keeper to safely keep her in prison until she “shal be thence delivered by due order of Law.”

Elizabeth was kept in prison until September 1691 when she was sentenced to hang for her crime. Previous to this case it was a crime in England to conceal the death of a bastard child. This law, though repealed in England by the time of the Emerson case, was still on the books in the Massachusetts Bay.

Therefore, while it was never sufficiently proven that she intentionally killed her children, such proof was unnecessary as their very concealment was considered to be a crime. She did maintain her innocence of the charge throughout the proceedings but that was of little consequence, even though by 1691 convictions on the charge of concealment of the death of a bastard were waning. Nathaniel Saltonstall’s comment that she had been examined for “whore-dom” was, perhaps, more to the point. It could be that the good people of Haverhill had tired of the antics of Elizabeth and had determined that being a whore, she could just as easily be a murderess. The society at large may have wanted to point to her as a warning to their own children. At the time, fewer and fewer of the children of the first settlers were owning the covenant and that was certainly a cause for great concern among the “saints.”

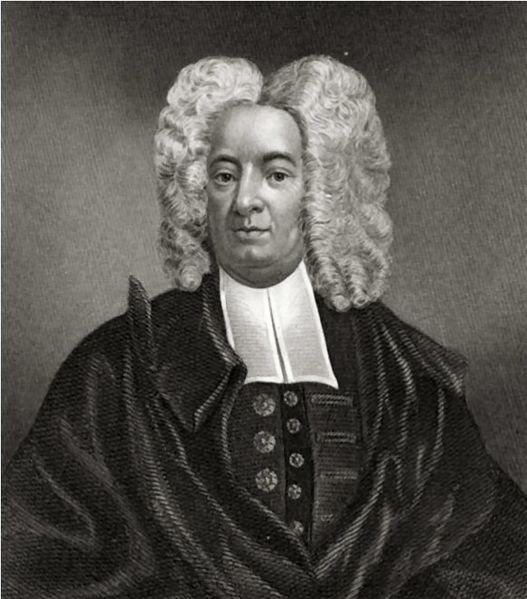

Cotton Mather Portrait c. 1700

Although convicted in Sep 1691 Elizabeth was not hanged until June 8, 1693. In the interim she came under the care and guidance of the Reverend Cotton Mather. How he found time to minister to Elizabeth while at the same time actively pursuing the Salem Witch Trials is unknown. Perhaps it was purely convenience, as Elizabeth was incarcerated in Boston, presumably with the unfortunate victims of the witchcraft hysteria. He did, however, get her to do something which nobody else could, to “confess.” During his sermon on Job 36:14 he read to the congregation what he claimed was a confession given him by Elizabeth. He writes that she confessed that “when they were born, I was not unsensible, that at least, One of them was alive; but such a Wretch was I, as to use a Murderous Carriage towards them, in the place where I lay, on purpose to dispatch them out of the World.” What did she mean by “murderous carriage?” Did she lay upon them or did she merely neglected them? Or were they, as per her initial assertion, truly stillborn?

According to Mather, she claimed that she should have listened to her parents, that she was “always of an Haughty and Stubborn Spirit.” and that “Bad Company” was what led to her downfall. Although her confession is very moving and seemingly sincere, Cotton Mather was not moved. He claimed that she “has more to confess, I fear…” and held little hope for her salvation. According to Mather “there never was Prisoner more Hard-Hearted, and more Unfruitful than you have been…”

It is a little puzzling that Mather was so disappointed with his prisoner. She did, after all, confess her crime and exhort the rising generation not to follow in her footsteps. Perhaps she did not confess readily enough to suit him. She was in prison for a little over two years and under those circumstances would surely have been broken into a confession at the hands of a less expert confessor than Mather. She may have continued to protest her innocence until very near the end, disappointing Mather who would have wanted to use her for his own ends.

Elizabeth was executed in Boston on that June day in 1693 and there her story ends. Dorothy, her daughter, also diseappeared from the record, and one can’t help but wonder at her fate. Michael, in his last will dated 1709, left distributions of a few shillings to at least some of his grandchildren, but Dorothy was noticeably absent.

Elizabeth may be seen in a number of different ways, as either victim or murderer, as evil or misguided. Her concealment of the birth seems unintellibible to many but in the context of a 17th century Puritan home it may be understandable, particularly in light of Michael Emerson’s known temper. That Samuel Ladd certianly bore responsiblity is undeniable. That he was not even questioned can only be seen as a result of his class and standing in the community. Was she coerced into sexual relations, and when the result was made known to him did he exhort her to silence? Perhaps, but by her own admission she had slept with Ladd many times. If he was the father of Dorothy as well as the twins they must have had a relationship lasting over five years. Such a relationship would not be seen as adulterous, as adultery was defined by the marital status of the woman.

But what of Michael Emerson’s charge in court that Timothy Swan was Dorothy’s father? The Swans and the Emersons were from the same social strata of Haverhill society. It may have been easier to try to claim paternity of his grandchild was the responsibility of an unmarried young neighbor than that of a high ranking, older married man. Perhaps Elizabeth herself, weighing the options, chose to lie to her father regarding Dorothy’s paternity, hoping that Timothy would marry her or seeking to protect Samuel from scandal. Eventually the truth must have come out as both of Elizabeth’s parents name Samuel Ladd without hesitation as the father of the twins. One thinks they may have known of their relationship prior to the discovery of the dead girls.

If Elizabeth had lived in the 20th century her life would have been very different. Rarely is the charge of whore-dom meted out today. In today’s society it would be her sister, Hannah Dustin, seen as the murderess, and Elizabeth as only an unfortunate girl, a victim of circumstance. But in the context of the 17th century Elizabeth was seen as the result of a moral degeneration that was very real and very frightening to Puritans of the first generation. A vast falling away from godliness in New England, not to be rectified until the next century’s Great Awakening. With nowhere to turn in her society, she sought to hide her pregnancy as long as possible, and when the twins were either born dead or died shortly thereafter, she took what steps she thought necessary to conceal her sin from her parents and from the community. How many others who did likewise were not caught

5. Deborah Corliss

Deborah’s first husband Thomas Eastman was born 11 Sep 1646 in Salisbury, Essex, Mass. His parents were Roger Eastman and Sarah [__?__]. Thomas died 29 Apr 1688 in Haverhill, Essex, Mass.

Deborah’s second husband Thomas Kingsbury was born 1653 in Ipswich, Essex, Mass. He first married Susanna Gage (b. 1617 d. 21 Feb 1678 in Haverhill). Thomas died 11 Jun 1720 in Plainfield, Windham, CT.

In 1676, Thomas Kingsbury was in the company of Lt. Benjamin Sweet in King Philip’s war; 1690 served under Sgt. John Webster at garrison east of Haverhill bridge

He was also active in other Indian wars and received land on the Saco River as a reward. Both Joseph and Thomas were in the Brick House garrison commanded by Thomas Dustin after the massacre of 1696/97 which took the lives of Thomas’s sons and probably his wife also.

In 1699-1700 Thomas appears to have received six shillings for serving on the committee to seat the meeting-house of Haverhill. In 1698 he made a committment to cut and carry two quarters of wood to the minister, Mr. Rolf. He also promised to attend meeting in the new house of worship when the glass was installed..

1706 captured by Indians; when released, moved to Plainfield

Wheareas thro’ the Goodnes of God Thomas Kingsbury is returned from a Long Captivity, and is not providentially Cast amongst us, and where as that he hath Lost most wch he had by the enemies, we the subscribers Look upon it our Duty to extend an act of Charity to him and that he maye have wherewith all to Live comfortably amongst us — we being the Lawfull proprietors of the Land within the Township of Plainfield — Be it known to all that maye be any way concerned that we the Subscribers do hereby give, grant, alloocate, and confirme unto the sd Thomas Kingsbury To his heirs and assigns for ever a certaine Tract or percell of Land To the quantity of Twenty acres Lying on the North Side of the River Moosup Bounded west on Land that is to be Laid out to James Kingsbury, the above Twenty acres is to be Laid out in Som sutable form bye persons appointed by the proprietors and the sd Kingsbury is to setle upon sd Land and upon these termes we do freelye give it to the above sd Kingsbury — to his heirs and assigns for ever to have and to hold the same as his own proper inheritance in fee simple with out mollestation for us our executors and Administrators, in witness hereunto that it is our own proper act and Deed we have hereunto set our hands for our selves, Oct. 7, 1708.

Deborah may have died Mar 15 1696 in the same Indian raid that killed her daughter Sarah.

In 1704, Deborah’s son Jonathan Eastman (b. 1681) was captured by Indians, His 8-day-old baby was killed. He rescued his wife Hannah Green 3 years later at Three River, Canada.

6. Ann Corliss

Ann’s husband John Robie was born 2 Feb 1649 in Exeter, Rockingham, New Hampshire. His parents were Henry Robie and Ruth Moore. Just two weeks after Ann died, John was killed by Indians 16 Jun 1691 in Haverhill, Essex, Mass. leaving 7 children none over 12 yrs. of age.

Children born in Haverhill Ruth, Ichabod, Henry, Joanna, Sarah, Deliverance, John, Mary.

7. Huldah Corliss

Huldah’s husband Samuel Kingsbury was born 25 Mar 1649 in Haverhill, Essex, Mass. His parents were Henry Kingsbury and Susanna Gage. Samuel died 26 Sep 1698 in Haverhill, Essex, Mass.

Samuel Kingsbury Gravestone — The Pentucket Cemetery is located on Water Street in Haverhill and was established in 1668. It’s located adjoining the Linwood Cemetery.

8. Sarah Corliss

Sarah’s husband Joseph Ayres was born 16 Mar 1658/59 Haverhill, Mass. His parents were John Ayres and Sarah Williams. Joseph died 30 Nov 1748 in Norwich, New London, CT.

Joseph was a planter or yeoman. He took the oath of allegiance and fidelity in Haverhill 28 Nov., 1677, with his father and brothers. Lived there until he removed to Ipswich, and thence about 1703 to West Farms (Franklin), Conn. John and Joseph Ayer settled at Preston and North Stonington as farmers. Joseph’s farm was within the bounds of “Norwich East Society” (part of Preston) where he was admitted an inhabitant in 1704. His mother’s brother, Joseph Williams, had come a short time before to this vicinity. Joseph Ayer brought his two sons with him; no doubt the other children came soon after, for they married in this neighborhood. He bought a large tract of land from Uncas (a Mohecan chief) and built the Ayer homestead in a narrow gap at the foot of Ayer’s mountain, known as Ayer’s Gap, where his father had settled before him.

Children of Sarah and Joseph

i. Joseph Ayres b. 8 MAY 1688 Haverhill, Mass.; d. 30 MAY 1688 Haverhill, Mass.

ii. Sarah Ayres b. 15 OCT 1690 Haverhill, Mass. d. 16 SEP 1753 Norwich, CT.; m. 30 SEP 1714 Norwich, CT. to Thomas Hazen. His parents were Lieut. Thomas Hazen and Mary Howlett. His grandparents were Edward HAZEN Sr. and Hannah GRANT.

iii. Abigail Ayres b. 8 SEP 1693 Haverhill, Mass.; m. Dennis Manough

iv. Joseph Ayres b. 23 DEC 1695 Haverhill, Mass.

v. Timothy Ayres b. 25 MAR 1698 Haverhill, Mass.

Source:

http://www.genealogyofnewengland.com/b_c.htm

http://www.angelfire.com/sc/whitefeather/Davis.html

http://familytreemaker.genealogy.com/users/f/l/e/Marion-Caswell-flemin/PDFGENE3.pdf

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~pattyrose/engel/gen/fg13/fg13_083.htm

“They Die in Youth And Their Life is Among the Unclean” The Life and Death of Elizabeth Emerson By Peg Goggin Kearney May 6, 1994 University of Southern Maine

Hannah Dustin: The Judgement of History By Kathryn Whitford Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.