Under Construction

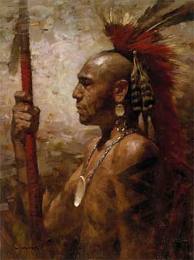

Uncas (1588 – 1683) was a sachem of the Mohegan who through his alliance with the English colonists in New England against other Indian tribes made the Mohegan the leading regional Indian tribe in lower Connecticut.

He was a friend and ally of our ancestor Major John MASON for three and a half decades and he had dealings with many other of our ancestors.

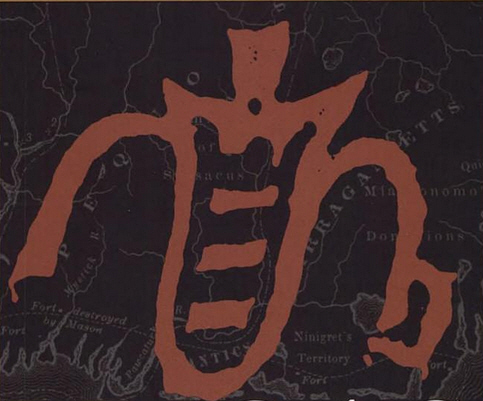

Uncas has acquired two different, divergent reputations. Most of the general public think of Uncas in the manner he was portrayed by Cooper, as epitomizing the “Noble Savage.” Some historians, however, regard the historical Uncas as a selfish conniver. Best known for his support of the New England colonies during the Pequot War in 1637, Uncas, acting at the behest of the Connectieut colony, gained notoriety for his role in the murder of the Narragansett sachem, Miantonomi, one of the first Native American leaders to advocate unity in the face of the European invasion. Who was the real man?

Navigate this Report

Origins

Pequot War

War with the Narragansett

King Philip’s War

Last of the

MohegansMohicans

Andrew Jackson’s Dedication

John Mason’s Controversial Statue

Connecticut Indians Today

A Final Word about History

3. Uncas and the Miner Ancestors

Founding New London

Pequot Property Rights

Great Swamp Fight

Mr. Fitch’s Mile

Norwich, CT

Preston, CT

- He was the the first, not the last.

Sachem Walkingfox – sachemuncas@centurylink.net

Before beginning the story of Sachem Uncas, also known as the Fox, for his abilities to outsmart all who wished him dead, I need to be sure that it is understood that the sources for some of this information was handed down by my Grandfather and other Elders and some was from other sources.

All of these teachings by my Mohegan Elders, took place at our monthly meetings, while I was growing up in Uncasvillage.

As computers, telephones or libraries did not exist in the time of Sachem Uncas, it would be nearly impossible to say that there is any source about him that is perfect.

It is very disturbing to me and my family to read all of the so called true stories about not only Sachem Uncas, but the Mohegan people as well, written by those who are neither Mohegan, nor even Native. How can one be an expert without living the story?

Walkingfox

Our English name became known as the Monheags. One of these groups of people became land diggers or farmers, however, most of the tribes in that area were warring tribes which over time, forced this group of Monheag People East. After some time and many forced movements, this group of Monheags ended up along the Quinatucquet River, which later became known as the Connecticut River in what is now Connecticut.

The many years of battles and losing their farms, taught this tribe how to fight, so that when the Mashantuckets, Missituks, Niantic’s, like the Mohawks had so long ago, came to destroy them and take their farms, the Monheags were ready for them, waging war first on them, then the Dutch and then the French. After this, the Dutch called them the Pequins, then the French changed their name to Pequods and the English changed it to Pequot’s.

Uncas was born about 1588 near the Thames River in present- day Connecticut. His father was the Mohegan sachem Owaneco. He was a descendant of the principal sachems of the Mohegan, Pequot, and Narragansett. Owaneco presided over the village known as Montonesuck. Uncas was bilingual, learning Mohegan and some English, and possibly some Dutch. In 1626, Owaneco arranged for Uncas to marry the daughter of the principal Pequot sachem Tatobem to secure an alliance with them. When Owaneco died, shortly after this marriage, Uncas had to submit to Tatobem’s authority. When in 1633, Tatobem was captured and killed by the Dutch, Sassacus became his successor. Owaneco’s alliance with Tatobem was based upon a balance of power between the Mohegan and Pequot. After the death of Owaneco, the balance changed in favour of the Pequot. Uncas was unwilling to challenge the power of Tatobem. After he died, however, Uncas began to contest Pequot authority over the Mohegan. In 1634 with Narragansett support, Uncas rebelled against Saccaucus and Pequot authority. He was defeated and Uncas became an exile among the Narragansett. He soon returned from exile after ritually humiliating himself before Saccacus. His failed challenge resulted in Uncas having little land and few followers.

The Mohegan tribe is an Algonquian-speaking tribe that lives in the eastern upper Thames River valley of Connecticut. Mohegan translates to “People of the Wolf”. At the time of European contact, the Mohegan and Pequot were one people, historically living in the lower Connecticut region. Before the early 17th century, under the leadership of Uncas, the Mohegan became a separate tribe, independent of the Pequot.

|

||

.

About 1635, Uncas developed relationships with important Englishmen in Connecticut. He was a friend of [our ancestor] Major John MASON, a partnership which was to last three and a half decades. Uncas sent word to Jonathan Brewster that Saccacus was planning to attack the English on the Connecticut river. Brewster described Uncas as being “faithful to the English”. In 1637, during the Pequot War, Uncas was allied with the English and against the Pequots. He led his Mohegan in a joint attack with the English against the Pequot near Saybrook and against their fort at Mystic River. The Pequot were defeated and the Mohegan incorporated much of the remaining Pequot people and their land.

Pequot War from The Wordy Shipmates

The Pequot War is a pure war. An by pure I don’t mean good. I mean it is war straight up, a war set off by murder and vengeance and fueled by misunderstanding, jealousy, hatred, stupidity, racism, lust for power, lust for land, and most of all, greed, all of it headed toward a climax of slaughter. The English are diabolical, The Narragansett and the Mohegan are willing accomplices, The Pequot commit distasteful acts of violence and are clueless as to just how vindictive the English can be when provoked. Which is to say that there’s no one to root for. Well, one could root for Pequot babies not to be burned alive, but I wouldn’t get my hopes up.

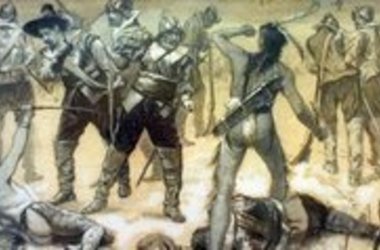

On 1 May 1637, the Connecticut General Court raised a force of 90 men to be under the command of Captain John Mason for an offensive war against the Pequot. Mason commanded the successful expedition against the Pequot Indians, when he and his men immortalized themselves in overthrowing and destroying the prestige and power of the Pequots and their fort near Mystic River, on the Groton side. During the attack, they killed virtually all of the inhabitants, about 600 men, women, and children. This event became known as the Mystic massacre.

Mason reports that on May 25

“about eight of the clock in the morning, we marched thence towards the Pequot with about five hundred Indians.

Their original aim was to attack the headquarters of Sassacus, the Pequot sachem, After all, it was Sassacus who had murdered Captain Stone to avenge his father’s death. But at some point, they decide to attack the Pequot fort at Mystic instead. It’s closer.

As the day wears on, they get hotter and hungrier. Mason says that “some of our men fainted.“

Mason writes : I then inquired of Uncas what he thought the Indians would do? Uncas predicts, “The Narragansetts would all leave us.” As for the Mohegan, Uncas reassures Mason that “he would never leave us: and so it proved. For which expressions and some other speeches of his, I shall never forget him, Indeed he was a great friend and did a great service.”

At night, recalls Mason “the rocks were our pillows, yest rest was pleasant.

The next morning, Mason asks Uncas and his comrade Wequash where the fort is. They tell him it’s on top of a nearby hill. Looking around Mason wonders where the hell the Narragansett have disappeared to. They are nowhere to be seen. Uncas replies that they’re hanging back “exceedingly afraid.” Mason tells Uncas and Wequash not to leave but to stand back and wait to see “whether Englishmen would now fight or not.“

Then Underhill joins in the huddle and he and Mason begin “commending ourselves to God.” They divide their men in half, “there being two entrances to the fort.“

The Pequot fort is encircled within a palisade, a wall made of thick tree trunks standing up and fastened together. Around seven hundred men, women and children are asleep in wigwams inside.

Mason writes that they “heard a dog bark.” Their sneak attack is foiled. Mason says they heard “an Indian crying Owanux, Owanx! Which is Englishman! Englishman!”

Mason: “We called up our forces with all expedition, gave fire upon them through the palisade, the Indians being in a dead – indeed their last – sleep.”

Mason commands the Narragansett and Mohegan to surround the palisade in what Underhill describes as a “ring battalia, giving a volley of shot upon the fort.” Hearing gunfire, the awakened Pequot, writes Underhill, “brake forth into the most doleful cry.”

The Pequot screams are so dolefule Underhill says the English almost sympathize with their prey – almost. Until the English manage to remember why they are there in the first place (to avenge the murder of various Englishmen from a drunken, wife-stealing pirate to the settlers on the Connecticut frontier whehn those girls were kidnapped. Thus Underhill reports “every man being bereaved of pitty fell upon the work without compassion, considering the blood [the Pequot] had shed of our native countrymen.”

Then the English enter the fort, carring, per Underhill ” our swords in our right hand, our carbines or muskets in our left hand.” Mason and Underhill start knocking heads inside the wigwams. Various Pequot come at them “Most courageously these Pequot behaved themselves”. Underwill will praise them later on.

Combat in the cozqy little bark houses is chaos – too dangerous and unpredictable. Mason is hit with arrows and Underhill’s hip is grazed. Mason is faced, on a smaller scale, with the same problem Harry Truman would confront when he was forced to ponder the logistics of invading Japan in 1945. A ground war would damn untold thousands of American troops to certain slaughter. The Puritan commander, in a smaller, grubbier, lower-tech way, arrives at the same conclusions as Truman when he ordered the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Mason says “We must burn them.

And they do,

Mason dashes inside a hut, lights a torch and “set the wigwam on fire.” The inhabitants are stunned. ”When it was thoroughly kindled,” Mason recalls, “the Indians ran as men most dreadfully amazed.”

Underhill, too, lights up his vicinity, and “the fires of both meeting in the center of the fort blazed most terribly and burnt all the space of half an hour.

The wind helps. According to Mason, the fire “did swiftly overrun the fort, to the extreme amazement of the enemy and great rejoicing of ourselves.” Mason notes that some of the Indians try to climb over the palisade and others start “running into the very flames.” They shoot arrows at the Englishmen who answer them with gunfire, but, writes Underhill, “the fire burnt their very bowstrings.”

“Mercy they did deserve for their valor.” Underhill admits of the Pequot. Not that they get any. William Bradford was told by a participant that “it was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fire, and the steams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stink and scent thereof.”

The Englishmen escape the flames and then guard the two exits so that no Pequot can escape. According to Underhill, those who try to get away “our soldiers entertained with the point of the sword; down fell men, women and children.”

Mason summarizes, “And thus … in little more than an hour’s space was their impregnable fort with themselves utterly destroyed, to the number of six or seen hundred.”

Two Englishmen died and about twenty are wounded. Mason is triumphant. After all, this is the will of a righteous God. He praises the Lord for “burning them up in the fire of his wrath, and dunging the ground with their flesh: It is the Lord’s doings, and it is marvelous in our eyes!” That might be the creepiest exclamation point in American Literature. No, wait – it’s this one: “Thus did the Lord judge among the heathen, filling the place with dead bodies!”

The Narragansett and Mohegan, whom Underhill calls “our Indians”, were shaken by the viciousness of the English and the horror of the carnage. Especially the Narragansett. Recall they had explicitly asked before the campaign, via Roger Williams, “that it would be pleasing to all natives, that women and children be spared.

“Our Indians,” Underhill writes, “Came to us much rejoiced at our victories, and greatly admired the manner of Englishmen’s fight, but cried ‘Mach it, mach it’ that is ‘It is naught. It is naught, because it is too furious and slays too many men.” The word “naught” to a seventeenth -century English speaker, meant “evil.”

He took a company of Englishmen up the river and rescued two English maids during this war. On 8 March 1637/8, in the aftermath of the Pequot War, the Connecticut General Court “ordered that Captain Mason shall be a public military officer of the plantations of Connecticut, and shall train the military men thereof in each plantation”. In the 1638 Treaty of Hartford, Uncas made the Mohegan a tributary of the Connecticut River Colony. The treaty dictated that Uncas could pursue his interests in the Pequot country only with the explicit approval of the Connecticut English. The Mohegan had become a regional power. In 1640, Uncas added Sebequanash of the Hammonasset to his several wives. This marriage gave Uncas some type of control over their land which he promptly sold to the English. The Hammonasset moved and became Mohegan.

The fire spread very rapidly and the people would not come out of the fort because they would be shot down. Because of the fire their bowstrings caught fire, they could no longer use bows and arrows. They had no distance weapons and, therefore, they had to fight with ax and knife, hand-to-hand, a very unequal combat. And I can imagine as that battle was going on, as Pequot men were running out with their clothes on fire attacking the English hand to hand I wonder what was going through Uncas’s mind. Because I think Uncas felt, well, this would be a typical battle on a fortification, the English will overcome them, they will surrender and maybe I’ll be able to take these people into my group. But instead everyone, 400 to 700 people were wiped out.

I cannot help but think that Uncas was horrified when he saw what happened, when he saw the tremendous violence that was unleashed by the English on the Pequot people and yet he does not turn against the English because he knows there’s nothing else he can do right now. It has begun. He has to follow it through to the end.

In gratitude to Uncas and the Mohegans, King Charles II gave Uncas a bible to show him the path to Heaven and a sword to protect himself from his enemies. Tribal legend has it that Uncas preferred the sword.

The success of Uncas and his tribe led to great change in the region’s power structure. The English triumphed against the Dutch. The Mohegans became the unrivalled native power. It was a controversial change that severed intertribal connections and relations.

After the Pequot War, in 1638, Uncas and 37 of his men made a ceremonial visit to Massachusetts Bay colony Gov. John Winthrop in Boston. At least 6 of the men accompanying Uncas were former Pequots, now Mohegans. The colonists accused Uncas of harboring the Pequot enemy. Uncas angrily denied breaking faith.

JOE BRUCHAC: That was when he made his famous speech about loyalty. And Uncas said these famous words. “If you do not trust me, you should kill me.” And then placing his hand on his heart he looked straight in Governor Winthrop’s eyes and said, “This heart is not mine, it is yours. I have no men. They are yours. Command me to do any hard thing and I will do it. I will never believe any Indian’s word against the English, and if any Indian shall kill an Englishman I will put him to death were he never so dear to me”, so spoke Uncas.

So you can see that Uncas was indeed both allying himself with the English and protecting his people including those former Pequots who now regarded themselves Mohegan.

.

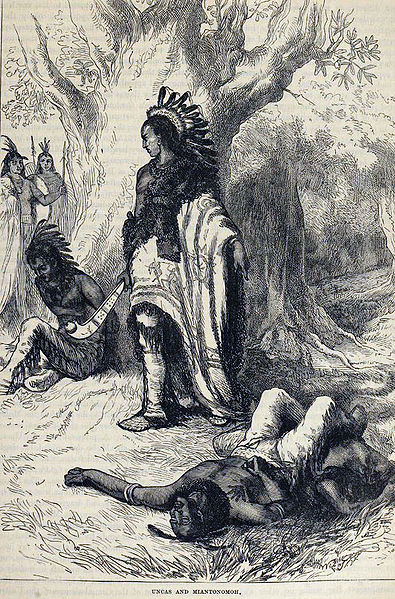

The Mohegan were in continuous conflict with the Narragansett over control over the former Pequot land. In the summer of 1643, this conflict turned into war. The English colonies formed an alliance, the New England Confederation, for their defence. The Mohegan defeated a Narragansett invasion force of around 1,000 men and captured their sachem Miantonomo.

Led by their Sachem, Miantonomo, who had a strong dislike for Uncas, a force of five to six hundred warriors marched against the Mohegans. In the summer of 1643, the Mohegans and Narragansetts met on the “Great Plain”. Uncas had perhaps half as many warriors as the Narragansetts. On the approach of the enemy, “Uncas sent forward a messenger, desiring a parley with Miantonomo, which was granted, and the two chiefs met on the plain, between their respective armies. Uncas then proposed that the fortunes of the day should be decided by themselves in single combat, and the lives of their warriors spared. His proposition was thus expressed: ‘Let us two fight it out; If you kill me, my men shall be yours; but if I kill you, your men shall be mine.’

Miantonomo, who seems to have suspected some crafty manoeuvre, in this unusual proposition, replied disdainfully, ‘My men came to fight, and they shall fight.’ Uncas immediately gave a pre-concerted signal to his followers, by falling flat upon his face to the ground. They, being all prepared with bent bows, instantly discharged a shower of arrows upon the enemy, and raising the battle yell, rushed forward with their tomahawks, their chieftain starting up and leading the onset. The Narragansetts, who were carelessly awaiting the result of the conference, and not expecting that the Mohegans would venture to fight at all with such inferior force, were taken by surprise; and after a short and confused attempt at resistance, were put to flight.”**

The battle lasted but a moment and Miantonomo, deserted by his people and over-weighted by an English corselet, was caught, after a long chase, by Uncas and one of his sachems.

Miantonomoh was slowed by his coat of mail and was taken prisoner. Uncas executed several of Miantonomo’s fellow warriors in front of him trying to solicit a response from Miantonomo. Miantonomoh suggested an alliance against the English to the sachem of the Mohegans, Uncas, but consistent with the 1638 treaty, Uncas turned him over to the Connecticut authorities at Hartford.

Miantonomoh was tried in Boston by the commissioners of the United Colonies of New England. A committee of five clergymen, to whom his case was referred, found him guilty. Although Miantonomoh had made war with their consent, they advised that he should be killed and gave Uncas authority to to put Miantonomo to death, provided that the killing was done in Mohegan territory. Miantonomoh was taken back to Norwich, where he had been defeated. Uncas’ brother Wawequa killed Miantonomo with a tomahawk under orders from Uncas.

Miantonomo ‘s son Canonchet was a Narragansett Sachem and leader of Native American troops during the Great Swamp Fight and King Philip’s War. He was a son of Miantonomo. In 1676, having been surprised and captured, his life was offered him on condition of making peace with the English, but he spurned the proposition. When informed that he was to be put to death, he said: “I like it well. I shall die before my heart is soft, and before I have spoken a word unworthy of Canonchet.”

When the next Narragansett sachem proposed to go to war to avenge the death of Miantonomo, the English pledged to support the Mohegan. The Narragansett attacks started in June 1644. With each success, the number of Narragansett allies grew. Uncas and the Mohegan were under siege at Shantok and on the verge of a complete defeat when the English relieved them with supplies and lifted the siege. The New England Confederation pledged any offensive action required to preserve Uncas in “his liberty and estate”. The English sent troops to defend the Mohegan fort at Shantok. When the English threatened to invade Narragansett territory, the Narragansett signed a peace treaty.

In 1646, the tributary tribe at Nameag, consisting of former Pequot, allied with the English and tried to become more independent. In response, Uncas attacked and plundered their village. The Bay Colony governor responded by threatening to allow the Narragansett to attack the Mohegan. For the next several years, the English both asserted the Nameag’s tributary status while supporting the Nameag in their independence. In 1655, the English removed the tribe from Uncas’ authority. The English had less and less use for Uncas, and his influence in English councils declined.

May 1649 – At the session of the General Court, the following regulations were made respecting Pequot in New London:

1. The inhabitants were exempted from all public country charges — i.e., taxes for the support of the colonial government — for the space of three years ensuing.

2. The bounds of the plantation were restricted to four miles each side of the river, and six miles from the sea northward into the country, ” till the court shall see cause and have encouragement to add thereunto, provided they entertain none amongst them as inhabitants that shall be obnoxious to this jurisdiction, and that the aforesaid bounds be not distributed to less than forty families.”

3. John Winthrop, Esq. [Col. Edmund READE’s son-in-law], with Thomas MINER and Samuel LOTHROP as assistants, were to have power as a court to decide all differences among the inhabitants under the value of forty shillings.

4. Uncas and his tribe were prohibited from setting any traps, but not from hunting and fishing within the bounds of the plantation.

5. The inhabitants were not allowed to monopolize the corn trade with the Indians in the river, which trade was to be left free to all in the united colonies.

6. ” The Courte commends the name of Faire Harbour to them for to bee the name of their Towne.”

7. Thomas MINER was appointed ” Military Sergeant in the Towne of Pequett,” with power to call forth and train the inhabitants.

.

The Mohegans and the planters at Pequot continued to be for several years troublesome neighbors to each other. The sachem was ever complaining o£ encroachments upon his royalties and the English farmers of Indian aggressions upon their property. In March, 1653/54, the planters, apparently in some sudden burst of indignation, made an irruption into the Indian territory and took possession of “Uncas his fort, and many of his wigwams at Monheag,”

The sachem, as usual, carried his grievances to Hartford ; and the General Court ordered a letter of inquiry and remonstrance to be written to the town. This was followed by the appointment of a committee. Major Mason, Matthew Griswold and Mr. Winthrop, to review the boundary line between the plantation and the Indians and to “endeavor to compose differences between Pequett and Uncas in love and peace.”- This appears to have quieted the present uneasiness, and for several succeeding years the enmity of the Narragansetts furnished the sachem with a motive to conciliate the English.

Between 1640 and 1660 he was repeatedly invaded by hostile bands of his own race, that swept over him like the gust of a whirlwind and drove him for refuge into some stone fort or gloomy Cappacummock. It is wonderful that he should always have escaped from an enmity so deadly and unremitting, and that he should have increased in numbers and strength while so frequently engaged in hostilities.

In 1657, the Narragansetts, taking their usual route through the wilderness, and crossing the fords of theShetucket and Yantic, poured down upon Mohegan, marking their course with slaughter and devastation.- Uncas fled before them, and took refuge in a fort at the head of Nahantick River, where his enemies closely besieged him. It is probable that he would soon have been obliged to submit to terms, had not his English neighbors hastened to his relief.

Lieut. James Avery, Mr. Brewster, Richard Haughton, Samuel LOTHROP and others well armed, succeeded in throwing themselves into the fort ; and the Narragansetts, fearing to engage in a conflict with the English, broke up the siege and returned home. Major John MASON, the patron of Uncas, hastened to lay before the General Court an account of the danger to which he had been exposed.-‘ The Legislature approved of the measures that had been taken for his protection, and requested Mr. Brewster to leave a few men in the fortress with Uncas, to defend him, if again he should be assaulted, and to keep a strict watch over the Narragansetts.

The commissioners who met at Boston in September, took a different view of the case. They had come to the determination of leaving the Indians to fight their own battles, and therefore disapproved of the interference of the English in favor of Uncas. A letter was forthwith dispatched to Pequot directing Mr. Brewster and the others, in Nahantick fort, to retire immediately to their own dwellings, and leave Uncas to manage his affairs himself. For the time to come, they prohibited any interference in the quarrels of Indians with one another, either by colonies or individuals, except in cases of necessary self-defense.

The next year Uncas was again invaded by the Narragansetts, and with them — united against their common enemy — came the Pokomticks and other tribes belonging to Connecticut River. The English did not always escape annoyance from these marauding parties. Mr. Brewster preferred a complaint to the commissioners at their next meeting, that the invaders

” Killed an Indian employed in his service, and flying to Mistress Brewster for succor ; yet they violently took him from her, and shot him by her side fo her great afirightment.”!

This incident undoubtedly occurred on Brewster’s Neck at Poquetannuck. The Indians in their defense said that the Mohegans, their enemies, took shelter in Mr. Brewster’s house and were there protected ; that Mr. Brewster and Mr. Thompson supplied them with guns, powder and shot ; that being on the west side of the river, they were shot at by two men from the east side, whereupon their young warriors crossed the stream, and not finding the offenders, concluded they had taken shelter in the house, and pursued them thither. This defense had but little weight with the commissioners ; who amerced the offending Indians in 120 fathoms of wampum.

The repeated invasion of his enemies drove Uncas for a time from his residence in Mohegan proper. He sheltered himself for two or three years within the circle of the English settlements, and dwelt at Xahantick, at Black Point, and even west of Saybrook, on lands claimed by him at Killing worth and Branford. It was not till after the settlement of Norwich in 1660, that he once more established himself in his old home.

The migratory habits of the Indians, who seldom spent summer and winter in the same place, will account in some degree for their wide-spread claims of possession. Foxen, the friend and counselor of Uncas has left his name indelibly impressed in the neighborhood of New London and on the plains of East Haven.- This fact alone would show the extent of the Mohegan right of dominion ; or rather of the Pequot right, to which the Mohegans succeeded.

In 1657, the court of commissioners, acting as agents to the “Society for propagating the Gospel in New England,” proposed to Mr. Blinman to become the missionary of the Pequots and Mohegans, offering a salary of £20 per annum, and pay for an interpreter. Mr. Blinman declined; and the same year Mr. William Thomson,^ a graduate of Harvard College, and son of the first minister of Braintree, Mass., was engaged for the office. His salary from the commissioners was £10 per annum, for the first two years, and £20 per annum, for tlie next two ; but after 1661 the stipend was withheld, with the remark, that he had ‘^ neglected the business.” His services were confined entirely to the Pequots at Mystic and Pawkatuck. ^ Uncas uniformly declined all ofEers of introducing religious

instruction among his people. Mr. Thomson left New London in feeble health in 1663, and in September, 1664, was in Surry county, Virginia.

The commissioners made many praiseworthy attempts to obtain regular religious instruction for the Pequots, but met with only partial success. In 1654, they selected John the son of Thomas MINER and proposed to educate him for an Indian teacher. John the son of Thomas Stanton was also received by them for the same purpose. They were both kept at school and college for two or three years ; but the young men ultimately left their studies and devoted themselves to other pursuits.

.

King Philip’s War started in June 1675. In the summer, the Mohegan entered the war on the side of the English. Uncas led his forces in joint attacks with the English against the Wampanoag. In December, the Mohegan with the English attacked the Narragansett, in the Great Swamp Fight.

An army was raised of one thousand men. The proportion of Connecticut was three hundred and fifteen, who were placed under the command of Major Robert Treat, of Milford, and ordered to rendezvous at New London.

New London county raised seventy men under Capt. John Mason, of Norwich, besides Pe-

quots andMohegans under Capt. Gallop. Of the seventy men Norwich contributed eighteen; New London, Stonington and Lyme, forty; Saybrook, eight; Killingworth, four. The whole force was to be at New London Dec. 10th. Great exertions were made to obtain the prequisite quantity of provisions and all the apparatus of war. Mr. Wetherell was the active magistrate, Joshua Raymond the commissary. Wheat was sent from other parts of the colony, here to be ground and baked. Indians were to be fitted with caps and stockings. The town also furnished a quantity of powder, bullets and flints, and ten stands of arms. At length there was an impressment of beef, pork, corn and rum, horses and carts, and the army marched.

The Mohegans in this fight were under the command of Capt. John Gallop, of Stonington, who was numbered among the slain. Capt. Avery had charge of the Pequots. It was afterward reported by some, that the Connecticut Indians would not fight in this battle, but discharged their guns into the air. This must bean error. Capt. Gallop, their gallant leader, was slain in the fury of the onset. No charge of cowardice or insubordination was brought against them after their return home ; while on the contrary, rewards for faithful service were bestowed on several. In the accounts of the county treasurer, are notices of cloth and provisions dealt out to various individuals, after they came from the battle. Among these are the names of Momoho, Nanasquee, Tomquash and his brother — “corn delivered Cassasinamon’s squaw,” and “blew cloth for stockings to Ninnicraft’s daughter’s Captayne and his brother.” Capt. John Mason, of Norwich, received a wound, with which he languished till the next September, and then died. The wounded men were mostly brought to New London to be healed, and were attended by Mr. Gershom Bulkley, the former minister of the town, who had accompanied the expedition in the capacity of surgeon.

In January, 1675/6, another army of one thousand men was raised*.. The Connecticut quota was again three hundred and fifteen ; their leader Major Treat, and their rendezvous. New London. They began their march on the 26th, passed through Stonington into the- Narragansett country, and from thence north-westerly into the Nipmuck region, clearing away the Indians in their course, but meeting

with no opportunity to strike a heavy blow. Uncas himself accompanied this expedition; and the Council of War wrote to Mr. Bulkley to return thanks for their good service, to Uncas and Owaneco of

the Mohegans, and to Robin Cassasinamon and Momoho of the Pequots. ‘

The Mohegan ended their active support of the English in this war in July 1676. Uncas died sometime between June 1683 and June 1684.

Sources:

http://www.simonpure.com/uncas.htm

http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-u/sp689.htm

http://www.nativeamericanmohegans.com/uncas.htm

http://www.sachem-uncas.com/sachemuncas.html

http://ctmonuments.net/2009/03/uncas-monument-norwich/

Uncas: First of the Mohegans By Michael Leroy Oberg 2003

Pingback: Uncas Legacy and Myth | Miner Descent

Pingback: Uncas and the Miner Ancestors | Miner Descent

Hi, I do think this is an excellent website. I stumbledupon it 😉 I will come back yet again since I book marked it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide other people.

Pingback: Gabriel Wheldon | Miner Descent