Most genealogies say Ensign John DAVIS (1621 – 1686) was killed at the Oyster River Massacre, he actually died a few years earlier, but the actual toll to his family is bad enough; daughter Sarah, son John Jr, daughter-in-law Elizabeth, grandson James and grandson Samuel all killed, two to four grandchildren carried off to Canada, one to live for fifty years as a French nun. Another son and grandson were killed by Indians in 1720 and 1724.

Yesterday, I found out that one of his granddaughters, Mary Smith, later married Thomas Freeman Jr, , son of our ancestor Deacon Thomas FREEMAN (1653 – 1716) who lived 150 miles away in Cape Cod. Did Mary escape or was she captured and taken to Canada? How did she get from New Hampshire to Harwich? Was the attack a treacherous massacre or justified act of war? I decided to make this post to share what I found out.

Navigate this Report

1. Overview

2.Background – King William’s War

3. French Perspective

4. Indian Perspective

5. English Perspective

6. Family Perspective

7. Aftermath

.

The Oyster River Massacre (known to the French and Indians as the Raid on Oyster River) happened during King William’s War, on July 18, 1694 at present-day Durham, New Hampshire.

Strictly speaking, this place formed part of the township of Dover until the year 1732, but it was five or six miles, from Dover proper, and was always a distinct settlement, and had a separate history from the first.

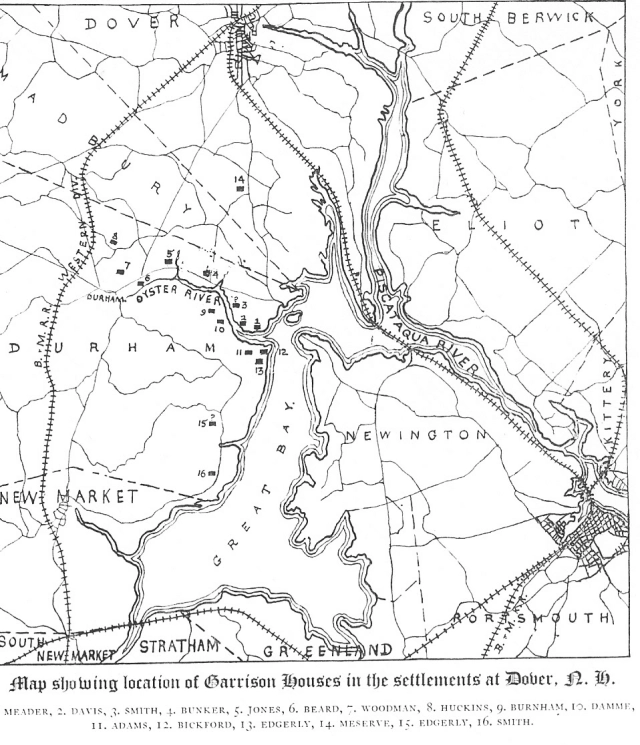

The name of “Oyster river” was given by the early pioneers to the Indian Shankhassick, a branch of the Piscataqua, on the banks of which they had found a bed of oysters. This stream has a channel broad and deep enough for shipping as far as the head of tide-water—that is, to the falls in Durham village, which is about two miles from its mouth and ten miles from Portsmouth harbor. There was no village here, however, in 1694. At that time there was a cordon of twelve garrisons along both sides of the river below, in which, at the least signal of danger from the Indians, those scattered settlers took refuge whose houses were without means of defense. But the meeting-house, the parsonage, the licensed tavern, and the center of local affairs were then on the south side of the river, more than a mile below the falls, on the tongue of land between the Oyster and Piscataqua rivers, now known as Durham Point.

This point is a rough, hilly tract of land, whose heights afford some delightful views across the tidal streams that enclose it. At that time Durham Point was alive with the activity of the early colonists, who were engaged in fisheries and in supplying lumber for a foreign market, as well as in agriculture.

A force of about 250 Indians under command of the French soldier, Claude-Sébastien de Villieu, and “the fighting priest” Fr. Louis-Pierre Thury attacked settlements in this area on both sides of the Oyster River, killing or capturing approximately 100 settlers, destroying five garrison houses and numerous dwellings. It was the most devastating French and Indian raid on New England during King William’s war.

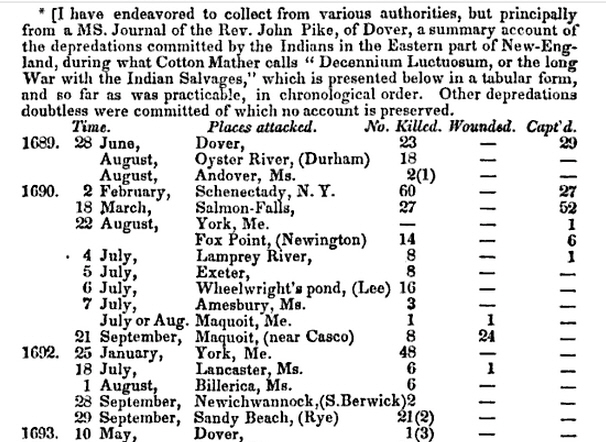

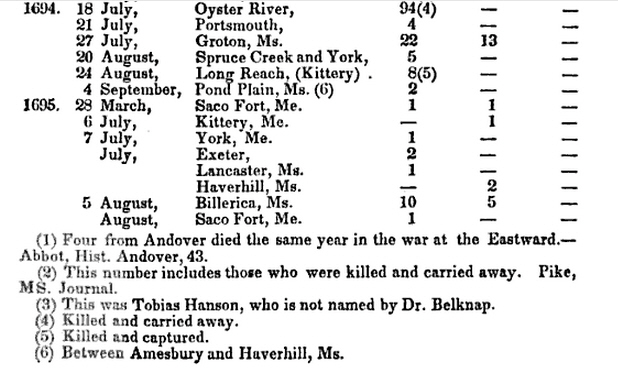

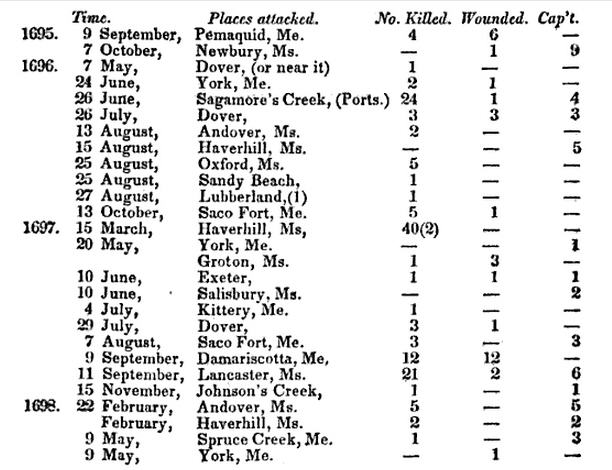

I’ve seen different estimates on the casualties

Reverend John Pike wrote in his diary:

The Indians fell suddenly & unexpectedly upon Oyster River about break of Day. Took 3 Garrisons (being deserted or not defended) killed & Carried away 94 persons, & burnt 13 houses- this was the f[i]r[st] act of hostility Committed by [them] after ye peace Concluded at Pemmaqd.

Wikipedia based on Acadia at the End of the Seventeenth Century by John Clarence Webster, Saint John, NB, The New Brunswick Museum, 1979 says

In all, 104 inhabitants were killed and 27 taken captive,[2] with half the dwellings, including the garrisons, pillaged and burned to the ground. Crops were destroyed and livestock killed, causing famine and destitution for survivors.

Jeremy Belknap, The History of New Hampshire, ed. John Farmer (Dover, N.H.: S.C. Stevens and Ela & Wadleigh, 1831)

94 killed and carried away

Another account says

In all, 45 inhabitants were killed and 49 taken captive, with half the dwellings, including 5 garrisons, burned to the ground. Crops were destroyed and livestock killed, causing famine and destitution for survivors.

2. Background – King William’s War

King William’s War was the North American theater of the Nine Years’ War (1688–97). It was the first of six colonial wars fought between New France and New England along with their respective Native allies before Britain eventually defeated France in North America in 1763.

England’s Catholic King James II was deposed at the end of 1688 in the Glorious Revolution, after which Protestants William and Mary took the throne. William joined the League of Augsburg in its war against France where James had fled.

In North America, there was significant tension between New France and the northern English colonies, which had in 1686 been united in the Dominion of New England. New England and the Iroquois Confederacy fought New France and the Wabanaki Confederacy,

The Wabanaki Confederacy was created by the five Indian tribes in the Acadia region in response to King Philip’s War. It was a political and military alliance with New France to stop the New England expansion.

The Iroquois dominated the economically important Great Lakes fur trade and had been in conflict with New France since 1680. At the urging of New England, the Iroquois interrupted the trade between New France and the western tribes. In retaliation, New France raided Seneca lands of western New York. In turn, New England supported the Iroquois in attacking New France, which they did by raiding Lachine.

There were similar tensions on the border between New England and Acadia, which New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine. English settlers from Massachusetts (whose charter included the Maine area) had expanded their settlements into Acadia. To secure New France’s claim to present-day Maine, New France established Catholic missions among the three largest native villages in the region: one on the Kennebec River (Norridgewock); one further north on the Penobscot River (Penobscot) and one on the St. John River (Medoctec)

Supplies were in short supply. For King William’s War, neither England nor France considered weakening their position in Europe to support the war effort in North America.

Many of our ancestors were involved in other parts of King William’s War: 1689 attacks of Dover NH, Saco ME, and the Siege of Pemaquid; Benjamin Church‘s raids on Acadia; the 1690 Battle of Fort Loyal; the 1690 Battle of Port Royal.; the 1690Battle of Quebec; and the 1691 attack on Wells, Me. It was a dangerous time t live in Maine and New Hampshire. I’ll have to make a post tying all these actions together.

In 1688 Sir Edmund Andros, Governor of the Dominion of New England, sailed the H.M.S. Rose into the harbor at the mouth of the Penobscot River. Once anchored, Andros sent his lieutenant ashore at Pentagoet to summon the Baron de St. Castin. St. Castin was a French army officer, who had established a trading post at Pentagoet near the mouth of the Penobscot. While he became the third Baron de Saint-Castin on the death of his elder brother in 1675, he appears to have devoted his time to becoming an Abenaki. He married a daughter of Madockawando, the highly respected principal chief of the Indians living along the Penobscot River. As the son-in-law of Madokawando. St. Castin enjoyed considerable influence among the Indians. The English, not wholly without merit, blamed the current Indian troubles on St. Castin. When the lieutenant returned with word that St. Castin had fled, Andros promptly seized the trading post. All movable goods were conveyed to the Rose, leaving behind only the vestments in St. Castin’s chapel. Many historians point to this raid as the beginning of King William’s War in the colonies.

During King William’s War, after Benjamin Church successfully defended a group of English settlers at Falmouth, Maine in the fall of 1689, Castin returned to the village in May 1690 with over 400 soldiers and destroyed the village. xxx

News of The Treaty of Pemaquid stunned the French command. From his base of operations at Fort Nashwaak on the St. John’s River, Joseph Robineau de Villebon understood full well the implications of this treaty. Except for a few regulars and Canadian militia, the Abenaki warriors constituted his entire military force. Their neutrality, or worse yet, their allegiance to the English, put all of Acadia in a very vulnerable position. Villebon moved immediately to counter the effects of the treaty. On September 6, 1693, he dispatched Manidoubtik, a St. John’s chief, to see the Penobscot chief, Taxous, on his behalf. Madockawando’s chief rival, Taxous refused to take part in the peace talks and opposed any accommodation with the English. Manidoubtik was to implore Taxous to raise a faction to end the peace pact.

On September 11, Father Louis-Pierre Thury, Jesuit missionary and the orchestrator of a 1692 raid on York (Maine), arrived at Fort Nashwaak. In this man of God, the English encountered their most dangerous enemy. Thury had established himself at Pentagoet in 1687 at the invitation of St. Castin. Thury regarded the English as heretics and accompanied the Indians on many of their raids. He had lately been at Quebec, but left for the fort at St. John’s as soon as news of the treaty became known. Thury reported to Villebon and the two agreed on a plan of action. Two days later, Thury departed for Pentagoet with the intention of fostering disapproval of Madockawando’s treaty.

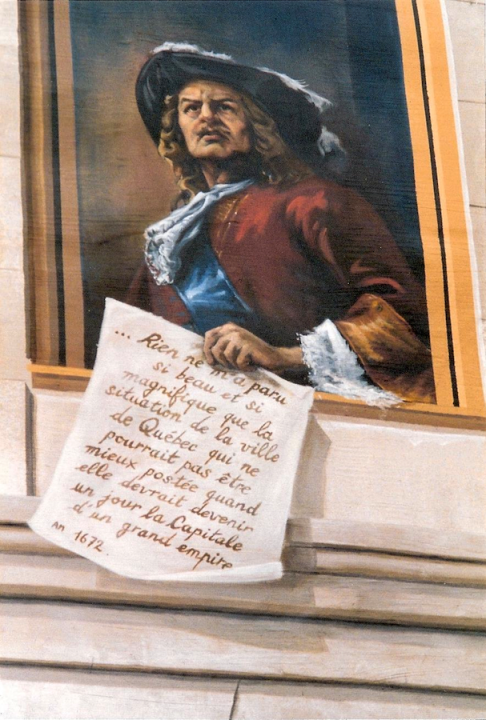

Governor General Frontenac of New France sent Claude-Sébastien de Villieu in the fall of 1693 into present-day Maine, with orders to “place himself at the head of the Acadian Indians and lead them against the English.” Villieu spent the winter at Fort Nashwaak. The Indian bands of the region were in general disagreement whether to attack the English or not, but after discussions by Villieu and cajoling by the Indians’ priest Fr. Thury (and with support from Fr. Bigot), they went on the offensive.

Claude-Sébastien de Villieu (1674–1705) was a French military officer best known for his service in New France. In addition to service during King William’s War, he served for a time as military governor of Acadia.

Villieu was a career soldier, having entered the French army in 1648 at the age of fifteen. Villieu fought well against the Iroquois in 1666 and was granted a tract of land on the St. Lawrence River. Despite having done little to develop his grant, Villieu sought loftier appointments. In 1690, he had command of a company of volunteers and acquitted himself favorably during Phips’ siege of Quebec. However, Villieu possessed little real experience in dealing with the problems of a frontier command. He was used to the harsh discipline and regimentation of the regular army. Except for the 1666 campaign, Villieu had spent little time away from the European settlements. At the age of sixty, he was completely unprepared for the undisciplined rigors of frontier life.

According to his own statement, he served for fifteen years on the battlefields of Europe, beginning in 1674, before coming to New France. He participated in the defense of Quebec when it was attacked by New England colonists in 1690. In 1692 he married Judith Leneuf, the daughter of Michel Leneuf de La Vallière de Beaubassin.

Villieu was n opportunist. Once out of Frontenac’s sight, Villieu sought to better his position in life. Neglecting his duties to Fort Nashwaak, he began a profitable business at the expense of the soldiers he was supposed to be commanding. He began appropriating supplies intended for his men to use in illegal trade with the Indians. Frontenac later commended Villieu for his efforts; at the same time, however, he summoned him to answer charges related to this trading.

Desiring nothing less than the governorship of Acadia, Villieu took advantage of every opportunity to discredit his commanding officer, Villebon. Villieu detested having to answer to a man twenty-two years his junior. He acted with insubordination and disregard for Villebon’s authority. It was clear upon Villieu’s arrival at Fort Nashwaak in November 1693 that he had no intention of carrying out his orders with regard to the treaty. Villieu’s arrival on the fifteenth coincided with the loss of a shipment of provisions intended for Villebon’s winter use. This contributed to the overall supply shortage, rendering many of the troops at the fort unfit for duty. This shortage of supplies remained a source of contention between the two men.

After the Raid on Oyster River he was rewarded with command of Fort Nashwaak (at present-day Fredericton, New Brunswick). He participated with Jean-Vincent d’Abbadie de Saint-Castin in Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville‘s successful Siege of Pemaquid in 1696. The ship carrying him from Pemaquid (in present-day Bristol, Maine) was captured, and he was imprisoned in Boston. Eventually released back to France, he returned to Acadia, where he served as the temporary governor from July 1700 to December 1701 after the death of governor Robineau de Villebon.

Little is known of the rest of his life. He was known to have difficult relations with his superiors, but was popular with the people in Acadia.

Louis-Pierre Thury (c. 1644, Notre Dame de Breuil, Normandy, France- 3 Jun 1699, Halifax, Nova Scotia), known to the English as “The Fighting Priest” was a French missionary who was a liaison between the French and their native American allies during King William’s War.

Thury had probably begun his theological studies in France. He arrived in Canada about 1675, where he finished his theological studies, and was ordained by Bishop Laval 21 Dec. 1677. He first served some parishes on both shores of the St. Lawrence and became busar of the seminary of Quebec.

In 1684, as the institution was planning to found a mission in Acadia, Bishop François de Laval sent Fr. Thury on an observation tour from Percé to Port-Royal (Annapolis Royal, N.S.). The missionary sent the bishop a long account and chose to settle at Miramichi, where Richard Denys offered a piece of ground for a mission. He remained there three years, receiving the visit of Bishop Saint- Valllier La Croix, and occasionally went to the Saint John River and Port-Royal.

On Abbé Petit’s advice, he then went to settle at Pentagouet (Castine, Maine), near Jean-Vincent d’Abbadie de Saint-Castin, where he remained eight years. He acquired great influence over the Abenakis and took part in their expeditions. In 1689 he accompanied Saint-Castin on the raid which resulted in the destruction of Pemaquid,; of this he left a detailed account. In 1692 he went along with a war party against York (Maine). Two years later he applied himself to thwarting the endeavors of Phips, who wanted to keep the Abenakis neutral; Thury played an important role in retaining them under French influence. He took part in the attack against Oyster Bay, and was present with Joseph Robineau de Villebon and a party of Abenakis at the capture of Pemaquid by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville in 1696.

The bishop of Quebec made him his vicar general in 1698 and appointed him to be the superior of the missions in Acadia. About the same time Fr. Thury founded a new mission at Pigiguit (on Minas Basin) and planned to group the Micmac people, in one huge settlement between Shubenacadie and Chibouctou. The court looked with favor upon this plan and granted him a sum of 2,000 livres. His death prevented him from carrying out this undertaking.

Fr. Thury died 3 June 1699 at Chibouctou and was buried by the Indians under a stone monument. Dièreville saw this monument and heard the hymns which the missionary had translated into Micmac.

Fr. Thury had a full career and was a successful missionary. His political role is more open to discussion and has been variously judged. The French officers praised his activity and Charlevoix represented him as a “true apostle,” whereas Parkman considered him merely an “apostle of carnage.”

In 1668, Father Bigot erected a chapel at Narantsouac, now Norridgewock, restoring the mission.

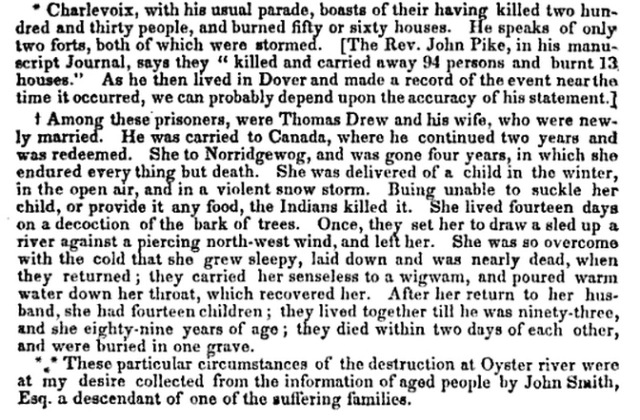

Where were theses Catholic missionaries during the carnage at Oyster River? Belknap only speaks of one; but according to the Durham tradition there were two priests in the expedition. They are said to have taken refuge in the meeting-house, and, without doubt, saved that building from destruction when the neighboring houses, including the parsonage, were burnt to the ground. No credit has been given them for this protection, and a poor return was made when our troops afterward pillaged and then burnt more than one Catholic church among the Indian missions of Maine. In view of this the priests in the Oyster River meeting-house may certainly be pardoned for the trifling act that has been made almost a matter of accusation against them. The local accounts say that while there they “amused themselves” in writing on the pulpit.

The Catholic missionaries seem to have done their utmost to rescue the women and children, at least, from the hands of the savages and place them in good families in Canada, where they were treated with invariable kindness and Christian charity, as is manifest from the accounts given at their return, several of which have been published. Most of the children, at least the girls, were sent to the schools at Quebec and Montreal to be educated, and some of these it is difficult to identify, for they generally received new Christian names in baptism, instead of the Old Testament names in vogue among the Puritans, and their surnames, uncouth to French ears, were phonetically recorded, and thereby transformed almost beyond recognition. Otis, for instance, was written Autes, Hotesse, and even Thys; Hubbard was changed to Ouabard; Willey to Ouilli, Houellet, and Willis; Wheeler to Huiller; Bracket to Bracquil, etc. These are all Oyster River or Dover names. One pupil was registered at Quebec as “Nimbe II.” Her real name was Naomi Hill. Many of the surnames were dropped in despair, and “Auglaise” substituted. Among tle captives at the Ursuline school in Quebec, about the year 1700, were Marie Elisabeth Anglaise, Marie Francoise Anglaise, Anne Marie Anglaise, and so on, to the number of eight or more, with no other -surname.

In western Maine, the years of 1687 and 1688 brought with them a heightening of tensions between the Abenaki and their English neighbors. Increased settlement, especially near the mouth of the Saco River, triggered a series of conflicts over fishing rights, livestock, and land ownership. The English placed nets across the Saco River, blocking migrating fish, a major Abenaki food source in the spring. English cattle continually damaged the local tribe’s unfenced corn fields. The leaders of the Saco Indians approached the English complaining, “that the corn, [the English had]promised by the last treaty, had not been paid, and yet their own was destroyed by the cattle of the English; and that they, being deprived of their hunting and fishing berths, and their lands, were liable to perish of hunger.”

The Abenaki complaints fell on deaf ears. English failure to address these complaints violated a 1685 treaty that established mechanisms for resolving such difficulties. Frustrated in their attempts at diplomacy, the Saco killed the offending cattle during the summer of 1688. In August, a dispute between settlers and Indians at North Yarmouth ended violently with casualties on both sides. Prompted by this Indian uprising, Benjamin Blackman, justice of the peace at Saco, ordered the seizure of twenty Indians that he suspected of causing the unrest. The Abenaki responded in kind, capturing several settlers during a raid on New Dartmouth in September 1688.

The Abenaki enjoyed considerable success at the start of the war. In June of 1689, several of the Eastern Indians joined with Kancamagus’ Pennacooks in an attack on Cocheco (Dover). That August, the English fort at Pemaquid Point (Maine) was destroyed. Later that same month, a party of sixty Indians returned to New Hampshire, burning the Huckins garrison at Oyster River.

After initial successes in King William’s War (1689-98), French and Native aggression waned. Little more that a side show in the Nine Year War, supplies to Canada, especially to Acadia, were often low. Native groups desiring trade goods in exchange for furs (and needing guns, powder, and lead) were at times forced to deal with the treacherously undependable English. With French supply shortages, a desire for trade goods, and the continued gains by the English military, some Penobscot and Kennebec factions felt compelled to sign a treaty with the Governor of Massachusetts, William Phips, at the newly rebuilt Fort William Henry at Pemaquid, Maine in 1693.

The reverses of 1692 and 1693 eroded the Abenaki willingness to continue the war. During the summer of 1693, a group of ten to thirteen chiefs, led by Madockawando, began to explore the possibility of peace. The humiliating failures at Wells and Pemaquid exposed the ineffectiveness of the French military alliance. The Abenaki found themselves deceived in the expectation of receiving assistance from the French. The cost of the war and lack of French support crippled the Abenaki economy. Continual war-parties interrupted traditional patterns of food gathering and fur production.

Late in July, Madockawando and his peace envoy approached the commander at Fort William Henry. Lamenting “the distress they have been reduced unto,” they expressed “their desires to be at peace with the English.” The chiefs sought to reopen their trade with the English, Boston being their nearest and best market. The English traded at rates that were much more advantageous than the French would agree to. The chiefs hoped that with improved relations they would be able to recover kinsmen captured by the English since the outbreak of King William’s War. The two parties entered into council and by August 11 th, reached an agreement. As proof of their fidelity, the sagamores gave four of their number into Governor Phips’ custody to be held as hostages.

The Treaty of Pemaquid was a one-sided document, reflecting English pretensions of innocence. The English either ignored or failed to see how their own actions contributed to the opening hostilities at Saco in 1687 and 1688. The treaty made the Abenaki the sole aggressors stating, “whereas a bloody war has for some years now past been made and carried on by the Indians.” [ The English wrongly attributed the war to the “instigation and influences of the French.”

While the English gained Madockawando consent to a treaty of peace, he was unable to persuade the chiefs who were under the influence of French Jesuit emissaries, and was compelled to recommence hostilities.

The English assumed that the thirteen signers of the treaty represented all the Indians “from the Merrimack River unto the most easterly bounds of said Province. ” This belief reflected a dangerous lack of understanding of Indian politics and social structure. While each tribe had a principal chief, there were several minor chiefs at the head of each village group. Abenaki politics relied on the “vagaries of social consensus.” Those chiefs who had not signed the treaty would not necessarily feel themselves bound by it. Not understanding this subtlety, the English assumed that the Indian peace envoy’s promises to “forbear all acts of hostility” and to “abandon the French interest” applied to all the Indians.

The treaty imposed humiliating conditions on the Indians, who conceded perhaps more than they realized. The very trade they were so desirous of now came under the strict control of the Governor and General Assembly of Massachusetts. They gave up their very freedom, “herby submitting ourselves to be ruled and governed by their Majesties’ laws.” ]In doing so, their only recourse in the event of a dispute lay in the English courts, which allowed the Indians no representation. In all likelihood, the Abenaki resented the treaty’s terms. Even the notoriously pro-French historian Charlevoix concluded that “these Indians often beheld themselves abandoned by the French, who counted a little too much on their attachment, and the influence of those who had gained their confidence.” ]Yet the Abenaki could not bear the cost of the war alone.

After being tipped off that Madockawando (a Penobscot), Edjeuemit (a Kennebec) and approximately ten others had signed this treaty, Villebon, Governor of Acadia, considered the 1694 spring war declarations of Taxous ( Madockawando’s Penobscot rival) all the more urgent and important.

As an international war party organized at the usual French and Native staging area of Pentegoet (Castine, Maine) French imperial interests were represented by Marine Captain Villeu, and the “Fighting Priest,” Thury.

Other parties from Nari Comagou (Canton Point, Maine) Ameseconti (Farmington Falls, Maine), and Norridgewock (Madison, Maine) started forming at Panawamske (the largest Penobscot village now in Old Town, Maine), and deliberated on a military target.

The name Old Town derives from “Indian Old Town”, which was the English name for the largest Penobscot Indian village, now known as Indian Island. Located within the city limits but on its own island, the reservation is the current and historical home of the Penobscot Nation

Now also joined by Maliseets from Meductic (Woodstock, New Brunswick) and Penobscots, the mobilized parties finally convinced the neutral “Madockawando faction” to take up the hatchet against the English. Fearing for the safety of clan relatives taken hostage by the English in Boston, the treaty group resisted until at last convinced by Madockawando’s son (recently returned from meeting Louis XIV in France), admonitions from Taxous, and arguments from Thury and Villeu. The French also claimed that past English “lies and betrayals” sealed the fate of the hostages and were said to now be slaves in England. Now on board, the peace faction joined the invasion force; all they needed was a target.

After an almost botched probe at Pemaquid, Villeu, who engaged in illicit fur trading throughout this part of the campaign, embezzled almost half of the French supplies. Therefore, as the army moved west towards the English settlements, through the river and portage routes, shortages started causing distress on the war trail. Picking up more warriors along the way, the group crossed over to the Merrimac River to Penacook (Concord, NH) by canoe, over the Ossippee/ Winnepesauke/ Merrimac River route. Now apparently near starvation, largely because of Villeu’s corruption, the war party decided upon Oyster River Plantation as a destination. A lucrative and easy enough target, it was also close, with a quick escape.

Bomazeen, a young, minor chief of the Kennebecs, played a significant role in the formation of the war-party and in the attack itself. Bomazeen had signed the Treaty of Pemaquid in 1693. Acting as an emissary of goodwill, he had traveled to Boston several times during the winter of 1693 to 1694. In late November, Bomazeen was thrown in prison by the order of the Lt. Governor of Massachusetts, where he stayed until midDecember. He was eventually released, but was committed twice more in January and March. Angered by this treatment, Bomazeen became a major proponent of an attack on the English. During the feast at Amasaquonte, the young chief was honored by being given command of a contingent of warriors for the coming attack.

Leaving the canoes at Penacook, and walking overland to Oyster River, the war party divided into smaller groups and moved down both sides of the river. The plan was to surround all the dwellings and garrisons and attack simultaneously by an agreed signal near dawn. Not completely in position, shooting broke out prematurely. Even in the chaos, the invaders “harvested” 104 dead and 27 prisoners.

From the start, the Indians were acting independently and not under the direction of Villieu. Although Villieu accompanied them and provided input, he did not lead them. Secondly, the Indians discussed among themselves where exactly to attack. It seems that Villieu’s only real contribution to the attack was to apprise his companions of the possible danger that they would be in if they stayed much longer. Villieu was leery of being surprised by a pursuing force bent on revenge. Thury conducted a brief mass, asking God to reward his charges for their valiant efforts. The war-party then withdrew to a nearby hill where they could safely sleep until the next day.

The following morning, fearing pursuit from the militia, the group returned to Penacook. Not at all satisfied with their uneven winning, the Penobscots under Taxous and Madockawando, along with some other of the “bravest”Kennebecs under Bomazeen, continued on the war trail down the Merrimac River to Groton, perhaps intending to attack Col. Johnathin Tyng in Dunstable, MA, taking an additional 22 dead and 13 more prisoners.

The Indian war continued for more than a year after the Peace of Ryswick had been concluded between France and England, until by the Treaty of Casco of 7 January 1699 the Penobscots acknowledged subjection to the crown of England. In the later operations Castin was their leader, Madockawando having been, perhaps, one of the chiefs treacherously slain by Capt. Pascho Chubb at a conference at Pemaquid in February 1696.

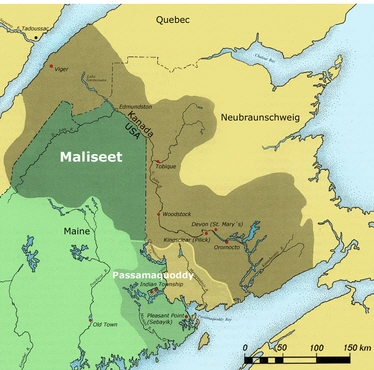

The Wabanaki Confederacy (translated roughly as ‘People of the First Light’ or ‘Dawnland’) comprises five principal Nations: the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki and Penobscot First Nations.

The Wabanaki peoples — are located in the area generally known to European settlers as Acadia. It is now most of Maine, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, plus some of Quebec south of the St. Lawrence River. The Western Abenaki are located in New Hampshire, Vermont, and into Massachusetts

The Wabanaki ancestral homeland stretches from Newfoundland, Canada, to the Merrimack Rivervalley in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Following the European invasion in the early 17th century, this became a hotly contested borderland between colonial New England and French Acadia. Beginning with King William’s War in 1688, members of the Wabanaki Confederacy of Acadia participated in six major wars before the British defeated the French in North America:

- King William’s War (1688–1697)

- Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713)

- Father Rale’s War (1722–1725)

- King George’s War (1744–1748)

- Father Le Loutre’s War (1749–1755)

- French and Indian War (1754–1763)

During this period, their population was not only radically decimated due to many decades of warfare, but also because of famines and devastating epidemics.

Wabanaki people freely intermarried with French Catholics in Acadia starting in 1610 after the conversion of Membertou. After 1783 Black settlers, refugees from the US, began to settle in the historical territory and many intermarriages between these peoples occurred, especially in southwest Nova Scotia from Yarmouth to Halifax. Suppression of Acadian, Black, Mi’kmaq and Irish people under British rule tended to force these peoples together as allies of necessity. Mixed-race children were commonly abandoned on reserves to be raised in Wabanaki tradition, as late as the 1970s.

The Wabanaki Confederacy was forcibly disbanded in 1862, but the five Wabanaki nations still exist, and they remain friends and allies – in part because all peoples claiming Wabanaki heritage have forebears from multiple Wabanaki and colonial ancestries.

The Penobscot main settlement is now Penobscot Indian Island Reservation.

Good Hearts, Stout Men – “The war party of 250 Abenaki Indians that moved through the darkness of the night, concealed within forests, was out for blood. Besides their own chiefs, at the head of the party was Sebastien de Villieu, a 60-year-old French military career officer, and Father Louis-Pierre Thury, a Jesuit priest. Father Thury had previously incited other Abenaki massacres of English Protestants whom he had hatefully considered to be heretics. The Abenakis were determined to slaughter or capture all the English colonists of the New Hampshire Oyster River Plantation, then butcher their livestock and set all their dwellings on fire.

When thirteen of the Abenaki chiefs signed the 1693 Treaty of Pemaquid the previous year, the French were alarmed that they might be losing their native allies for further prosecution of their war against the English. Father Thury and other Frenchmen insidiously influenced the younger chiefs to reject what the thirteen older chiefs had decided, suggesting that they were weak-willed cowards who planned to sell tribal land to the encroaching English. The best way to insure future Abenaki loyalty, the French knew, was to induce the disaffected chiefs to mount a treaty-breaking raid against an English settlement. After that, there could be no turning back until the French made peace with the English. Initial war councils of the young chiefs in 1694 had favored Boston as the target of their intended terror, but the Abenakis changed the site of battle to the Oyster River Plantation.

[For the English, the Treaty of Pemaquid was a master stroke. Many of the frontier settlements lay in ruins. Settlers confined to garrisons could not harvest crops. Food shortages were common. Commerce and trade were at a standstill. But now, with the Eastern Tribes under control, New England was free to muster her forces for a second attempt on Quebec. Flushed with success, Phips sent runners to the frontier settlements to proclaim the peace. To a war-weary region this was welcome news indeed. As fall gave way to winter, and no new outbreaks occurred, the settlers began to leave the garrisons, returning to their homes. ]

Only two days before the slaughter, the Oyster River settlers had gathered to belatedly hear — and to cheer — news of the Treaty of Pemaquid. Feeling safe from attack, the neighbors let their guard down, ending the long-held night watches along both sides of the Oyster River.”

The Indian war party approached from the west after sunset, and divided their forces into two divisions, one attacking along the river’s south side and the other on the north side. Detachments of eight to ten Indians were then tasked to strike each of the 12 fortified garrisons and other strong-houses. The Indians believed that settlers in unfortified houses would rush to the garrisons for protection, only to find the Indians waiting to kill them down outside the already-besieged garrisons.”

Jeremy Belknap, continues the story in The History of New Hampshire, ed. John Farmer (Dover, N.H.: S.C. Stevens and Ela & Wadleigh, 1831)

The towns of Dover and Exeter being more exposed than Portsmouth or Hampton, suffered the greatest share in the common calamity.

The engagements made by the Indians in the treaty of Pemaquid, might have been performed if they had been left to their own choice. But the French missionaries had been for some years very assiduous in propagating their tenets among them, one of which was ‘ that to break faith with heretics was no sin.’ The Sieur de Villieu, who had distinguished himself in the defence of Quebec when Phips was before it, and had contracted a strong antipathy to the New-Englanders, being then in command at Penobscot, he with M. Thury, the missionary, diverted Madokawando and the other Sachems from complying with their engagements; so that pretences were found for detaining the English captives, who were more in number, and of more consequence than the hostages whom the Indians had given.

The settlement at Oyster river, within the town of Dover, was pitched upon as the most likely place; and it is said that the design of surprising it was publicly talked of at Quebec two months before it was put in execution.

Rumors of Indians lurking in the woods thereabout made some of the people apprehend danger; but no mischief being attempted, they imagined them to be hunting parties, and returned to their security. At length, the necessary preparations being made, Villieu, with a body of two hundred and fifty Indians, collected from the tribes of St. John, Penobscot and Norridgewog, attended by a French Priest, marched for the devoted place.

The enemy approached the place undiscovered, and halted near the falls on Tuesday evening, the seventeenth of July. Here they formed two divisions, one of which was to go on each side of the river and plant themselves in ambush, in small parties, near every house, so as to be ready for the attack at the rising of the sun; and the first gun was to be the signal.

John Dean, whose house stood by the saw-mill at the falls, intending to go from home very early, arose before the dawn of day, and was shot as he came out of his door. This firing, in part, disconcerted their plan; several parties who had some distance to go, had not then arrived at their stations; the people in general were immediately alarmed, some of them had time to make their escape, and others to prepare for their defence. The signal being given, the attack began in all parts where the enemy was ready.

Of the twelve garrisoned houses five were destroyed, viz. (11.) Adams’s, Drew’s, (13.) Edgerly’s, (1.) Medar’s and (6.) Beard’s. They entered (11.) Adams’s without resistance, where they killed fourteen persons ; one of them, being a woman with child, they ripped open. The grave is still to be seen in which they were all buried. Drew surrendered his garrison on the promise of security, but was murdered when he fell into their hands. One of his children, a boy of nine years old, was made to run through a lane of Indians as a mark for them to throw their hatchets at, till they had dispatched him. Edgerly’s was evacuated. The people took to their boat, and one of them was mortally wounded before they got out of reach of the enemy’s shot. Beard’s and Medar’s were also evacuated and the people escaped.

The defenceless houses were nearly all set on fire, the inhabitants being either lulled or taken in them, or else in endeavoring to fly to the garrisons. Some escaped by hiding in the bushes and other secret places. Thomas Edgerly, by concealing himself in his cellar, preserved his house, though twice set on fire. The house of John Buss, the minister, was destroyed, with a valuable library. He was absent; his wife and family fled to the woods and escaped. The wife of John Dean, at whom the first gun was fired, was taken with her daughter, and carried about two miles up the river, where they were left under the care of an old Indian, while the others returned to their bloody work. The Indian complained of a pain in his head, and asked the woman what would be a proper remedy : she answered, occapee, which is the Indian word for rum, of which she knew he had taken a bottle from her house. The remedy being agreeable, he took a large dose and fell asleep ; and she took that opportunity to make her escape, with her child, into the woods, and kept herself concealed till they were gone.

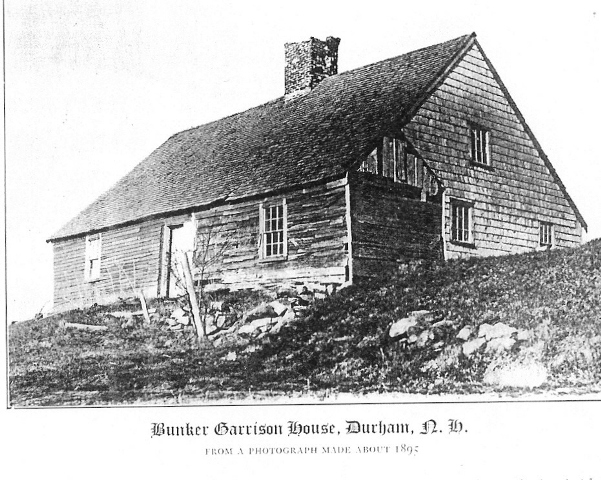

James Bunker built a fortified home in 1652 known as Bunker’s Garrison (4. on map above) in the Oyster River Plantation area. Two soldiers were assigned to his garrison and he was paid £5/6/0 for their upkeep between 25 Jul 1693 and 24 Nov 1694.

The other seven garrisons, viz. (9.) Burnham’s, (12.) Bickford’s, (3.) Smith’s, (4.) Bunker’s, (2.) Davis’s, (5.) Jones’s and (7.) Woodman’s were resolutely and successfully defended. At Burnham’s, the gate was left open : The Indians, ten in number, who were appointed to surprise it, were asleep under the bank of the river, at the time that the alarm was given. A man within, who had been kept awake by the toothache, hearing the first gun, roused the people and secured the gate, just as the Indians, who were awakened by the same noise, were entering. Finding themselves disappointed, they ran to Pitman’s defenceless house, and forced the door at the moment, that he had burst a way through that end of the house which was next to the garrison, to which he with his family, taking advantage of the shade of some trees, it being moonlight, happily escaped.

Bunker Garrison Plan — The walls, except the gable ends, were of hewn hemlock logs, nine inches in thickness. There were loopholes for defence which were afterward enlarged into windows.

Still defeated, they attacked the house of John Davis, which after some resistance, he surrendered on terms; but the terms were violated, and the whole family was either killed or made captives.

Thomas Bickford preserved his house (12.) in a singular manner. It was situated near the river, and surrounded with a palisade. Being alarmed before the enemy had reached the house, he sent off his family in a boat, and then shutting his gate, betook himself alone to the defense of his fortress. Despising alike the promises and threats by which the Indians would have persuaded him to surrender, he kept up a constant fire at them, changing his dress as often as he could, shewing himself with a different cap, hat or coat, and sometimes without either, and giving directions aloud as if he had a number of men with him. Finding their attempt vain, the enemy withdrew, and left him sole master of the house, which he had defended with such admirable address.

Davis-Smith Garrison – The drawing of the Davis-Smith garrison in what today is Newmarket is shown in its latter days just before being torn down in 1880. Probably built ca. 1694 by David Davis, it was taken over (and perhaps rebuilt) by John Smith around 1701, after Davis had been killed by Indians.

Smith’s, Bunker’s and Davis’s garrisons, being seasonably apprised of the danger, were resolutely defended. One Indian was supposed to be killed and another wounded by a shot from Davis’s. Jones’s garrison was beset before day; Captain Jones hearing his dogs bark, and imagining wolves might be near, went out to secure some swine and returned unmolested. He then went up into the flankart and sat on the wall. Discerning the flash of a gun, he dropped backward; the ball entered the place from whence he had withdrawn his legs. The enemy from behind a rock kept firing on the house for some time, and then quitted it. During these transactions, the French priest took possession of the meeting-house, and employed himself in writing on the pulpit with chalk; but the house received no damage.

Those parties of the enemy who were on the south side of the river having completed their destructive work, collected in a field adjoining to Burnham’s garrison, where they insultingly showed their prisoners, and derided the people, thinking themselves out of reach of their shot. A young man from the sentry-box fired at one who was making some indecent signs of defiance, and wounded him in the heel: Him they placed on a horse and carried away. Both divisions then met at the falls, where they had parted the evening before, and proceeded together to Capt. Woodman’s garrison. The ground being uneven, they approached without danger, and from behind a hill kept up a long and severe fire at the hats and caps which the people within held up on sticks above the walls, without any other damage than galling the roof of the house.

At length, apprehending it was time for the people in the neighboring settlements to be collected in pursuit of them, they finally withdrew; having killed and captivated between ninety and an hundred persons, and burned about twenty houses, of which five were garrisons. The main body of them retreated over Winnipiseogee lake, where they divided their prisoners separating those in particular who were most intimately related.

Mary Smith Freeman

Mary Smith was born 24 May 1685 in Oyster River, Stafford, New Hampshire. Her parents were James Smith and Sarah Davis. Her parents were killed in King William’s War, her father in 1690 and her mother and two brothers in the Oyster River Massacre 18 Jul 1694 in Durham, New Hampshire. Her grandparents were our ancestors Ensign John DAVIS and Jane PEASLEE.

She married 13 Nov 1707 Eastham, Barnstable, Mass to Thomas Freeman Jr. (b. 12 Oct 1676 Harwich, Barnstable, Mass – d. 22 Mar 1715/16 Orleans, Barnstable, Mass) His parents were our ancestors Thomas FREEMAN and Rebecca SPARROW. Thomas had married first Bathsheba Mayo, but she died four months after their marriage. After Thomas died, Mary married again aft. Mar 1717 in Eastham, Barnstable, Mass. to Hezekiah Doane (1672 – 1752) Mary died in 1732 in Eastham, Barnstable, Mass.

I wonder how Mary came the 150 miles from New Hampshire to marry and live in Eastham on Cape Cod. Around 1700, most marriages were within the same towns.

Here’s a romanticized version I found where Thomas was a mariner who had business at Oyster River where he met Mary, fell in love and brought her home to the Cape to be married. I’m not sure of the author,but, I’ve updated a little of the florid 19th Century language and omitted incorrect details like their mother scooping babes Samuel and James into her arms since they were actually 11 and 13 years old.

In the days of the French and Indian Wars, the town of Durham, [today home to the University of New Hampshire], was called Oyster River. The scattered farmhouses were guarded by six or eight garrison houses. Nothing lay between the settlements and Quebec, but the unbroken wilderness known only to the Indians, the fur traders and the marauding war parties which were sent out against each other by Catholic Canada and Protestant New England.

Mary Smith lived at the Inn which was kept by her father James Smith and her mother Sarah Davis in Oyster River N.H. The people lived in constant terror of attack. Mary’s father was killed by the Indians, and Mary’s mother took her five children and moved into the garrison house near by with her brother Ensign John Davis.

July 18, 1694 some 200 Indians led by 20 French Canadians and 2 Catholic Priests burst, without warning, on the sleeping village. The garrison house of Ensign Davis, Mary’s Uncle, was quickly surrounded. One of the French leaders and a Catholic priest promised safety for him and his household if he surrendered. He took them at their word, realizing all too well, that alone he could not hold out long. The instant he unbolted the door, he was rushed upon by the Indians, tomahawked and scalped, together with is wife and two of their children while the two older girls were seized as captives. When Mary’s mother saw what was happening, she shouted for her children to run for their lives out the back door. Somehow, Mary, her sister Sarah, and brother John made their escape and hid in the woods. [Mary’s brothers James (1681 – 1694) and Samuel (1683 – 1694) were not so lucky.]

Twenty-eight of Mary’s closest relatives met death that morning. In all, 104 inhabitants were killed and 27 taken captive, with half the dwellings, including the garrisons, pillaged and burned to the ground. But Mary was not to be taken captive. In a few days Captain Tom Freeman from Cape Cod was heading his lumber schooner in toward Oyster River for a load of sawn boards. He found several frightened, bewildered people who told him of the massacre. He loaded no lumber that trip but began to search along the bank and in the woods for all those he could possibly save.

Among this group was our ancestor Mary Smith. She was taken to Tom Freeman’s father’s home which was in Harwich, Mass. Mary was reared and educated by those fine people and when she grew up she married the youthful sea captain who had rescued her – Captain John Freeman _ Mary Smith Freeman.

From the family Bible – we read in Mary’s own precise handwriting –

Mary Smith born May 24, 1685 Md Tom Freeman November 13, 1707

In a short ten years her husband was dead and she a widow at thirty-three with four little children. The final line of the record reads – My husband Thomas Freeman deceased March 22, 1718.

Mary’s sister Sarah came to Eastham to marry Joshua Harding in 1702. So a more likely scenario is that Mary came to visit, or even live, with Sarah and met Thomas then.

Judith Davis

Ensign John DAVIS‘ daughter Judith, wife of Captain Samuel Emerson, was also taken by the Indians and remained in captivity five years.

Judah Emerson — From – New England Captives Carried to Canada Between 1677 and 1760

By Emma Lewis Coleman

Mary Ann Davis

Ensign John DAVIS”s granddaughter, daughter of John Davis is one the most interesting of the captives taken at Oyster River, July 18, 1694. According to a constant tradition in Durham, became a nun in Canada and refused to return home at the redemption of captives in 1699. This was Sister St. Benedict, of the Ursuline convent, Quebec, the first native of New Hampshire, if not of New England, to embrace the conventional life.

Mary Anne Davis was seven years old when the Indians, on the above-mentioned day, burnt her father’s house and killed him and his wife and several children, as well as his widowed sister and two of her sons. They spared, however, his two young daughters,- whom they carried into captivity, but who, unfortunately, were separated.

One of them, named Sarah, was afterwards redeemed, and was living at Oyster River October 16, 1702, on which day her maternal uncle, Jeremiah Burnham, was appointed her guardian and the administrator of her father’s estate. She afterwards married Peter Mason, but was left a widow before 1747. Sarah inherited her father’s land at Turtle Pond and also his homestead on the south side of the Oyster River. With true Davis tenacity to life she was still living in 1771, when she sold part of her homestead lands to John Sullivan (afterwards General in the Revolutionary army, delegate in the Continental Congress, Federal judge, and Governor of New Hampshire). How much longer she lived does not appear. She left one daughter, at least, whose descendants can still be traced.

Though John Davis was killed in 1694 no attempt was made to administer on his estate till after his daughter Mary Anne’s religious profession, September 25, 1701, when all hope of her return home was renounced.

But to return to her sister, who chose the better part. Mary Anne was carried away by the Abenaki Indians, but was rescued not long after by Father Rale, who instructed and baptized her and conveyed her to Canada. In 1698 she entered the boarding-school at the Ursuline convent, Quebec. At her entrance into this “Maison des Vierges” of which she had heard among the Abenakis, she was transported with joy. “This is the house of the Lord,” she cried; “it is here I will henceforth live; it is here I will die.” She entered the novitiate of that house on St. Joseph’s day, March 19, 1699; and received the religious habit and white veil, with the name of Sister St. Benedict, the fourteenth of September following—the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. She took the black veil and made her vows September 25, 1701. Mademoiselle de Varennes, whose father was governor of Trois Rivieres for twenty-two years, took the white veil with her and made her vows at the same time. The latter was only fourteen years of age when she entered the novitiate.

Sister St. Benedict is said not to have known her own age, but was supposed to be a few years older. The trials she had undergone, however, must have given her an air of maturity beyond her years The Durham tradition does not mention her age, but speaks of her as “young” when taken captive. She died March 2, 1749. Her death is entered in the convent records as follows:

“The Lord has just taken from us our dear Mother Marie Anne Davis de St. Benoit after five months’ illness, during which she manifested great patience. She was of English origin and carried away by a band of savages, who killed her father before her very eyes. Fortunately she fell into the hands of the chief of a village who was a good Christian, and did not allow her to be treated as a slave, according to the usual practice of the savages towards their captives. She was about fifteen years old when redeemed by the French, and lived in several good families successively in order to acquire the habits of civilized life and the use of the French language. She everywhere manifested excellent traits of character, and appreciated so fully the gift of Faith that she would never listen to any proposal of returning to her own country, and constantly refused the solicitations of the English commissioners, who at different times came to treat for the exchange of prisoners. Her desire to enter our boarding-school in order to be more fully instructed in our holy religion was granted, and she soon formed the resolution to consecrate herself wholly to Him who had so mercifully led her out of the darkness of heresy. Several charitable persons aided in paying the expenses of her entrance, but the greater part of her dowry was given by the community [i.e., by the Ursulines themselves] in view of her decided vocation and the sacrifice she made of her country in order to preserve her faith.

Her monastic obligations she perfectly fulfilled, and she acquitted herself with exactness of the employments assigned her by holy obedience. Her zeal for the decoration of the altar made her particularly partial to the office of sacristan. Her love of industry, her ability, her spirit of order and economy, rendered her still very useful to the community, though she was at least seventy years of age.

“She had great devotion to the Blessed Virgin and daily said the rosary. Her confidence in St. Joseph made her desire his special protection at the hour of death—a desire that was granted, for she died on the second of March of this year 1749, after receiving the sacraments with great fervor, in the fiftieth year of her religious life.”

There was another Mary Ann Davis who became a nun in Canada in early times. She was, likewise, a captive from New England. She became a nun at the Hotel Dieu, Quebec, in 1710, under the name of Sister St. Cecilia. She was taken to Canada by the Rev. Father Vincent Bigot, S.J., who had ransomed her from the Indians at St. Francis. She is mentioned as leading ” a holy life” for more than fifty years in the religious state. She died in 1761, at the age of seventy-three. There is no record of her birthplace or parentage. She may have been the daughter mentioned by the Rev. John Pike, of Dover, N. H., in his journal:

“August 9, 1704, The wife, son, and daughter of John Davis, of Jemaico, taken by ye Indians in yr house or in yr field.” [Jemaico was part of Scarborough, Maine.]

The people of Oyster River Plantation were not sacrificed on the altar of fate. Their deaths reflected the accomplishment of a very real strategic objective. The Abenaki went to war in order to protect their land and their way of life. The signing of the Treaty of Pemaquid, by a small group of disaffected chiefs, demanded action from both the French and Native Americans. The attack on Oyster River was the successful culmination of their joint action.

Immediately following the 1694 massacre, the British assigned 20 soldiers to protect

the remaining Oyster River residents. Records show that at least three soldiers were

posted “at Bunker’s” and note payments “James Buncker” made to the soldiers before the first inter-colonial war ended in 1697 — which is also the year that James Bunker died.

The sacrifice and valor of the Oyster River settlers was eloquently heralded by the leading Puritan intellectual and firebrand preacher Cotton Mather in his 1699 history, Decennium Luctuosum, or “Sorrowful Decade.”

New France and the Wabanaki Confederacy were able to thwart New England expansion into Acadia, whose border New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine.

In the North American theatre the French had been on the ascendant; all the English assaults on French possessions had been repulsed; Fort Penobscot on the border of Acadia had been destroyed; the frontiers of both New England and New York had been ravaged and forced back; the English outposts in Newfoundland had been destroyed and the island virtually conquered. In addition, throughout the war England’s claims to the Hudson Bay had been severely contested in a series of French expeditions culminating in Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville‘s capture of York Factory shortly before the signing of the treaty.

In spite of this the Treaty of Ryswick,signed on Sep 1697 returned the territorial borders to where they had been before the war (status quo ante bellum). The Iroquois nation, deserted by their English allies, continued to make war on the French colonies until the Great Peace of Montreal of 1701.

The Oyster River Environs Archaeology Project (OREAP) is a multidisciplinary study bringing professionals from the fields of archaeology, history, geology, geography, and the environmental sciences together with interested members of the public to reconstruct the cultural history and land use patterns of the prehistoric and historic peoples who have lived within the Oyster River and Lamprey River watersheds.

Goals of the OREAP:

1. Site Chronology and Settlement Patterns – Radio carbon dating, the historical record, and artifact typology will be used to establish occupational sequences and settlement layouts. This will provide a framework for studying cultural change/ continuity and land use patterns.

2. Reconstruction of Economies – Economies of subsistence, manufacture, and trade will be reconstructed as a means to understanding how people made their living and interacted with other cultural groups.

3. Social Hierarchies, Politics, and Religion – The above provides a framework for assessing social structure within the community, relations with other communities, and the role of religion in everyday life.

4. Cultural Continuity/ Change – All of the above will provide a framework for the reconstruction of a cultural history for the region. Change and continuity will be assessed in relation to the larger Piscataqua Region and New England as a whole.

Sources:

The History of New Hampshire, by Jeremy Belknap, ed. John Farmer Dover, N.H.: S.C. Stevens and Ela & Wadleigh, 1831

http://massandmoregenealogy.blogspot.com/2011/08/mary-smith-freeman-1685-1766-oyster.html

http://www.unh.edu/users/unh/acad/libarts/cnec/exhibit1/oysterriver.html

http://massandmoregenealogy.blogspot.com/2011/08/mary-smith-freeman-1685-1766-oyster.html

http://www.nedoba.org/ne-do-ba/menh_or94.html

The Catholic Church in New Hampshire THE CATHOLIC WORLD: A MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF GENERAL LITERATURE AND SCIENCE VOL. LII NOVEMBER 1890

http://www.unh.edu/users/unh/acad/libarts/cnec/exhibit1/oysterriver.html

Pingback: Ensign John Davis | Miner Descent

I have a massacre in my family history also. See The Light in the Forest – http://bramanswanderings.wordpress.com/2012/06/18/the-light-in-the-forest/

I need to write more about it. This was only an introduction. It looks as though you plan to add to your account.

Thanks for sharing.

Pingback: Deacon Thomas Freeman | Miner Descent

Direct descendant from a family in this massacre. (still live in the area as well). Nice info here.

Descendent of Abraham Clark. I am always searching for info on anything on Oyster River plantation and massacre

I’m a descendant of Abraham too! I have him married to Deliverance Drew and their daughter Sarah is my 8th Great Grandmother.

Pingback: Indian Kidnaps | Miner Descent

Pingback: Favorite Posts 2013 | Miner Descent

Thank you for this information! I am a descendent of Ensign John Davis and Jane Peasley and their daughter, Judith.

Hi. How did you establish your lineage?

James Sr Davis 1583

Ensign John J Davis and Jane Peasley

Moses Davis 1657

John Davis 1682

Nathaniel Davis 1716

Elijah Davis 1750

Elijah Davis 1788

Samuel Davis 1871

Andrew Jackson Davis 1836

Charles Davis 1867 my GGG

8th gen.descendent of madakawondo.thanks for info.

Love this and thank you for all the work. DD to John And James Davis. Were they really Twins? And did they have daughters born on the same day.

Hi Lore,

Which generation do you mean? I have a brother James who was two years older (b. 1619) than this Ensign John Davis.

And this John Davis had sons John and James born eleven years apart (1651 and 1662)

kind regards, Mark

Yes That is the James I am speaking of. It is recorded as the same date of birth as his brother in most ancestry records. I never believed it. Do you have an actual date? Do you know which of the girls were taken. It has been suggested one was Mary. That can’t be right. Thank you for responding. I have a few more questions, but need to get organized. There are several confusions with the brothers. Also every one and their brother credits birth from James Davis and Cicely Thayer. That is 1 of 2 major confusions in the data regarding the Davis Clan. I have not read this completely, but thanks to people like you we can make fact out of confusion. Great Job.

Thank you for the informative article. Am a direct descendant of Ensign John Davis, my GGF being a Davis from this line…as well as one tough SOB.

Hi Jack. Beatrice Davis Black’s daughter, Deborah would like to know if your GGF Davis had a large farm on Dover Point back in the 1920’s and 1930’s???

jabez davis was my ancestor

I read more and found my answer. Thanksyou.

Pingback: 10. LBRY and Privatized Police : The Freecoast – Fostering the Growing Liberty Movement in Seacoast NH

Pingback: 10. LBRY and Privatized Police - The Freecoast

Mary Smith is my 8th gr GM, she married Capt. Thomas Freeman on Oct 17 1707 in Eastham MA. The story is incredible and sounds fictional

Thank you for sharing this. I am a descendant of “old man Huckins” Robert Huckins, killed in 1694 raid. I read Col Benjamin Church’s accounts of rescuing Sarah (Burnham) Huckins in 1690.

Just an FYI, I’m a descendant of Sarah Davis Mason. Thank you for getting the dates for John Davis, Sr who did in 1686, and his son, John Jr who died in the massacre of 1694. And a well written article, as well.

Looking for information on William and Thomas Drew, Brothers. Thomas Drew died in this Oyster River Massacre.

I would guess the Drew mentioned here that opened upon false pretenses was the Dad. Of Which I have little information, concerning parentage. When Thomas was Killed off his young wife Mary married Richard Elliot. The other Brother William survived the massacre.

I am a DD of James Davis (b 1583 Wiltshire, England) & Cicely Thayer (b 1600 England), who bore James Davis (b 1619), who married Elisabeth Eaton (b 1625), who bore Elisha Davis (b 1670), who married Grace Shaw (b 1670), who subsequently bore Moses Davis (b 1711). Moses enlisted in the Continental Army and fought the British. My family history includes experiences in both King Philip’s War (The First Indian War) and King William’s War (The Second Indian War).

Is there a complete list of the families who settled in the Oyster River Settlement and surrounding areas between 1690 into early-to-mid 1700s?

Who prepared this main document? Michael Behrendt, Town Planner, Durham, NH. Thank you.