This post includes ancestors who were portrayed in Shakespeare’s plays, inspired characters, connected with Shakespeare or with figures in his Histories.

Navigate this Post

1. Shakespeare’s Life

2. The Tempest

3a. The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

3b. Antony and Cleopatra

4. Macbeth

5. The Life and Death of King John

6. Henry IV Part 1

7. Henry IV Part 2

8. Henry IV Part 3

9. Richard III

10. Henry VIII – All Is True

Shakespeare’s Life

Edward BROWN (1574 – 1610) and his son Nicholas BROWN (1601 – 1694) were born in Inkberrow Parish, Worcestershire, England that is often thought to be the model for Ambridge, the setting of the long running radio series The Archers. In particular ‘The Bull’, the fictional Ambridge pub, is supposed to be based on a very real pub, the Old Bull, in Inkberrow. It is at this historic public house or wayside inn, a black and white half-timbered building, that William Shakespeare is reputed to have stayed while on his way to Worcester to collect his marriage certificate.

The Tempest

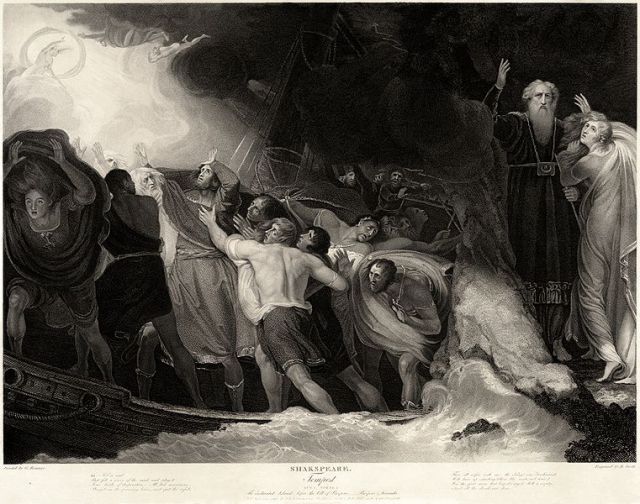

The Tempest, believed to have been written in 1610–11, is thought by many critics to be the last play that Shakespeare wrote alone. (Modern scholars believe Henry VIII to be a collaboration between William Shakespeare and John Fletcher – see below)

The story of the Sea Venture shipwreck (and Hopkins’ mutiny) is said to be the inspiration for the play. Our ancestor Stephen HOPKINS is believed to be the model for the character Stephano.

Peter MONTAGUE’s daughter-in-law Cecily Reynolds’s second husband Samuel Jordan (wiki) was also shipwrecked on the Sea Venture.

Capt Edmund GREENLEAF’s second wife Sarah Jordan was the daughter Ignatius Jordan (wiki), a leading Puritan (known at”The Arch-Purtian”) and Member of Parliament. Sarah’s uncle Silvester Jourdaine was the companion of his townsmen Sir George Somers Sir Thomas Gates and Captain Newport in their voyage to America in 1609 and was wrecked with them at Bermuda. On his return home Silvester Jourdaine published A Discovery of the Barmudas otherwise called the Isle of Divels 1610, a pamphlet from which Shakespeare is supposed to have drawn material for The Tempest.

Stephen was the only Mayflower passenger who had previously been to the New World. His adventures included surviving a the Sea Venture’s 1609 shipwreck in Bermuda [including being pardoned for mutiny!] and working from 1610–14 in Jamestown as well as knowing the legendary Pocahontas, who married John Rolfe, a fellow Bermuda castaway.

Stephen may be the real life inspiration for Stephano in the Tempest, played in the 2010 film version by Alfred Molina

William Strachey‘s A True Reportory of the Wracke and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight, an eyewitness report of the real-life shipwreck of the Sea Venture in 1609 is considered by most critics to be one of Shakespeare’s primary sources because of certain verbal, plot and thematic similarities. Although not published until 1625, Strachey’s report, one of several describing the incident, is dated 15 July 1610, and critics say that Shakespeare must have seen it in manuscript sometime during that year.

Strachey was no stranger to the theater people who met regularly at the Mermaid Tavern, so it’s probable that Shakespeare was among those who got a preview of the work.

Several years later, the Virginia Company published a heavily sanitized version of Strachey’s A True Reportory fearing that if the public knew the truth about Jamestown, there would be no more recruits.

In the 19th century Sylvester Jourdain’s pamphlet, A Discovery of The Barmudas (1609), was proposed as that source, but this was superseded in the early 20th century by the proposal that “True Reportory” was Shakespeare’s source because of perceived parallels in language, incident, theme, and imagery.

The Tempest is set on a remote island, where Prospero, the rightful Duke of Milan, plots to restore his daughter Miranda to her rightful place using illusion and skillful manipulation. He conjures up a storm, the eponymous tempest, to lure his usurping brother Antonio and the complicit King Alonso of Naples to the island. There, his machinations bring about the revelation of Antonio’s low nature, the redemption of the King, and the marriage of Miranda to Alonso’s son, Ferdinand.

Stephano is a boisterous and often drunk butler of King Alonso. He, Trinculo and Caliban plot against Prospero. In the play, he wants to take over the island and marry Prospero’s daughter, Miranda. Caliban believes Stephano to be a god because he gave him wine to drink which Caliban believes healed him.

Stephano’s Quotes

The master, the swabber, the boatswain, and I,

The gunner, and his mate,

Lov’d Mall, Meg, and Marian, and Margery,

But none of us car’d for Kate;

For she had a tongue with a tang,

Would cry to a sailor Go hang!

She lov’d not the savour of tar nor of pitch,

Yet a tailor might scratch her where’er she did itch.

Then to sea, boys, and let her go hang!

This is a scurvy tune too; but here’s my comfort. (Drinks)

Act 2: Scene II

Caliban: Hast thou not dropp’d from heaven?

Stephano: Out o’ th’ moon, I do assure thee; I was the Man i’ th’ Moon, when time was.

Caliban: I have seen thee in her, and I do adore thee. My mistress show’d me thee, and thy dog and thy bush.

Act 2: Scene IIFlout ’em and scout ’em, and scout ’em and flout ’em;

Thought is free.

Act 3: Scene IIHe that dies pays all debts.

Act 3: Scene II

Hodges writes, “To have provided some of the fabric for Shakespeare’s vision of The Tempest and to appear in the play, even in the absurd disguise as Stephano, this in itself is a kind of immortality for Stephen Hopkins.”

Stephen was fined on 19 May 1608 at the Merdon Manorial Court, however, the reason was not recorded. Stephen’s lease at Hursley’s Merdon Manor was turned over to a “Widow Kent.” The Hopkins family either moved out or was forced out.

Stephen Hopkins’ Real Island Adventure

In 1609 Stephen left his wife and three small children to sign on with the Third Supply, a fleet of nine ships taking 500 settlers and supplies to Jamestown. Having no money to invest, and no rank of any kind, Stephen’s name does not appear on the list of Virginia Company investors. Instead, he is lumped with the anonymous “sailors, soldiers, and servants” on the fleet’s flagship, the Sea Venture.

In his contract with the Virginia Company, Stephen would serve three years as an indentured servant, his labors profiting those who had financed the venture. In exchange, he would receive free transportation, food, lodging, and 10 shillings every three months for his family back home. At the end of three years, he would be freed from his indenture and given 30 acres in the colony.

On Jun 2 1609, the Sea Venture, under the command of Sir George Somers, admiral of the fleet, with Christopher Newport as captain and Sir Thomas Gates, Governor of the colony, departed from Plymouth, England followed by the rest of the Virginia Company’s fleet, the Falcon,Diamond, Swallow, Unity, Blessing, Lion, and two smaller ships.

Hodges writes,

“For seven weeks the ships stayed within sight of each other, often within earshot, and captains called to one another by way of trumpets. On the Sea Venture all was peaceful. Morning and evening, Chaplain Buck and Clerk Hopkins gathered the passengers and crew on deck for prayers and the singing of a psalm.”

The ships were only eight days from the coast of Virginia, when they were suddenly caught in a hurricane, and the Sea Venture became separated from the rest of the fleet. The Sea Venture fought the storm for three days. Comparably sized ships had survived such weather, but the Sea Venture had a critical flaw in her newness: her timbers had not set. The caulking was forced from between them, and the ship began to leak rapidly. All hands were applied to bailing, but water continued to rise in the hold. The ship’s guns were reportedly jettisoned (though two were salvaged from the wreck in 1612) to raise her buoyancy, but this only delayed the inevitable.

William Strachey chronicled the Sea Venture’s final days:

“On St. James Day, being Monday, the clouds gathering thick upon us and the wind singing and whistling most unusually, a dreadful storm and hideous began to blow from out the northeast, which, swelling and roaring as it were by fits, at length did beat all night from Heaven; which like a hell of darkness, turned black upon us . . . For four-and-twenty hours the storm in a restless tumult had blown so exceedingly as we could not apprehend in our imaginations any possibility of greater violence; yet did we still find it not only more terrible but more constant, fury added to fury, and one storm urging a second more outrageous than the former . . . It could not be said to rain. The waters like whole rivers did flood in the air. Winds and seas were as mad as fury and rage could make them. Howbeit this was not all. It pleased God to bring greater affliction yet upon us; for in the beginning of the storm we had received likewise a mighty leak.”

The ship had begun to take on water and every man who could be spared went below to plug the leaks and work the pumps. The men worked in waist-deep water for four days and nights, but by Friday morning they were exhausted and gave up.

Another chronicler, Silvester Jourdain, wrote that some of the men,

“having some good and comfortable waters [gin and brandy] in the ship, fetched them and drunk one to the other, taking their last leave one of the other until their more joyful and happy meeting in a more blessed world.”

Then there was a crash and the Sea Venture began to split seam by seam as the water rushed in. Jourdain continues:

“And there neither did our ship sink but, more fortunately in so great a misfortune, fell in between two rocks, where she was fast lodged and locked for further budging; whereby we gained not only sufficient time, with the present help of our boat and skiff, safely to set and convey our men ashore . . . “

The Sea Venture had been thrown upon a reef about a mile from Bermuda, then known as the “Isle of the Devils.” Those who could swim lowered themselves into the waves and grasped wooden boxes, debris, or anything that would keep their heads above water. Stephen made it to shore clutching a barrel of wine. The entire crew, including the ship’s dog, survived.

As it turned out, the Sea Venture did not break apart and the men were able to retrieve the tools, food, clothing, muskets, and everything that meant their survival. Most of the ship’s structure also remained, so using the wreckage and native cedar trees, the 150 castaways immediately set about building two new boats so that they could complete their voyage to Jamestown.

The ship’s longboat was fitted with a mast and sent to Virginia for help, but it and its crew were never seen again.

The men were pleasantly surprised to find that the island’s climate was agreeable, food plentiful, and shelters easily constructed from cedar wood and palm leaves. The Isle of the Devils, turned out to be paradise, and a few began to wonder why they should leave.

Strachey recounts that some of the sailors, who had been to Jamestown with the Second Supply, stated that

“in Virginia nothing but wretchedness and labor must be expected, there being neither fish, flesh, or fowl which here at ease and pleasure might be enjoyed.”

The first attempt at mutiny was made by Nicholas Bennit who “made much profession of Scripture” and was described by Strachey as a “mutinous and dissembling Imposter.” Bennit and five other men escaped into the woods, but were captured and banished to one of the distant islands. The banished men soon found that life on the solitary island was not altogether desirable and humbly petitioned for a pardon, which they received. But the clemency of the Governor only encouraged the spirit of mutiny.

William Strachey notes that while Stephen HOPKINS was very religious, he was contentious and defiant of authority and had enough learning to wrest leadership from others. On January 24, while on a break with Samuel Sharpe and Humfrey Reede, Stephen argued:

“. . . it was no breach of honesty, conscience, nor Religion to decline from the obedience of the Governor or refuse to goe any further led by his authority (except it so pleased themselves) since the authority ceased when the wracke was committed, and, with it, they were all then freed from the government of any man . . .[there] were two apparent reasons to stay them even in this place; first, abundance of God’s providence of all manner of good foode; next, some hope in reasonable time, when they might grow weary of the place, to build a small Barke, with the skill and help of the aforesaid Nicholas Bennit, whom they insinuated to them to be of the conspiracy, that so might get cleere from hence at their own pleasures . . . when in Virginia, the first would be assuredly wanting, and they might well feare to be detained in that Countrie by the authority of the Commander thereof, and their whole life to serve the turnes of the Adventurers with their travailes and labors. “

The mutiny was brought to a quick end when Sharpe and Reede reported Stephen to Sir Thomas Gates who immediately put him under guard. That evening, at the tolling of a bell, the entire company assembled and witnessed Stephen’s trial:

“. . . the Prisoner was brought forth in manacles, and both accused, and suffered to make at large, to every particular, his answere; which was onely full of sorrow and teares, pleading simplicity, and deniall. But he being onely found, at this time, both the, Captaine and the follower of this Mutinie, and generally held worthy to satisfie the punishment of his offence, with the sacrifice of his life, our Governour passed the sentence of a Maritiall Court upon him, such as belongs to Mutinie and Rebellion. But so penitent hee was, and made so much moane, alleadging the ruine of his Wife and Children in this his trespasse, as it wrought in the hearts of all the better sorts of the Company, who therefore with humble entreaties, and earnest supplications, went unto our Governor, whom they besought (as likewise did Captaine Newport, and my selfe) and never left him untill we had got his pardon.”

Stephen begged and moaned about the ruin of his wife and children, and was pardoned out of sympathy. After pleading his way out of a hanging, Stephen continued his duties as Minister’s Clerk and worked quietly with the others to finish the construction of the ships from Bermuda cedar and materials salvaged from the Sea Venture, especially her rigging.

Some members of the expedition died in Bermuda before the Deliverance and the Patienceset sail on 10 May 1610. Among those left buried in Bermuda were the wife and child of John Rolfe, who would found Virginia’s tobacco industry, and find a new wife in Chief Powhatan‘s daughter Matoaka (Pocahontas). Two men, Carter and Waters, were left behind; they had been convicted of unknown offences, and fled into the woods of Bermuda to escape punishment and execution.

On May 10, 1610, the men boarded the newly built Deliverance and Patience and set out for Virginia. They arrived in Jamestown on May 24, almost a full year after they had left England.

On reaching Jamestown, only 60 survivors were found of the 500 who had preceded them. Many of these survivors were themselves dying, and Jamestown itself was judged to be unviable. Everyone was boarded onto the Deliverance and Patience, which set sail for England. The timely arrival of another relief fleet, bearing [our ancestor] Governor Thomas WEST, 3rd Baron de la Warr, which met the two ships as they descended the James River, granted Jamestown a reprieve. All the settlers were relanded at the colony, but there was still a critical shortage of food. Somers returned to Bermuda with the Patience to secure provisions, but died there in the summer of 1610. His nephew, Matthew, the captain of the Patience, sailed for England to claim his inheritance, rather than return to Jamestown. A third man, Chard, was left behind in Bermuda with Carter and Waters, who remained the only permanent inhabitants until the arrival of the Plough in 1612.

Stephen appears to have been a bit of a rebel on board the Mayflower, a dissenter questioning the authority of the Separatist leaders, just as he had a decade earlier on the Sea Venture. Stephen was a member of a group of passengers known to the Pilgrims as “The Strangers” since they were not part of the Pilgrims’ religious congregation. Storms forced the landing to be at the hook of Cape Cod in what is now Massachusetts. This inspired some of the passengers perhaps led by Stephen to proclaim that since the settlement would not be made in the agreed upon Virginia territory, they “would use their own liberty; for none had power to command them…”

To prevent this, many of the other colonists chose to establish a government and sign the Mayflower Compact, a document outlining how their new society would run. Hopkins was one of forty-one signatories of the Mayflower Compact and was an assistant to the governor of the colony through 1636.

See Stephen HOPKINS‘ page for more of his adventures including the First Encounter and sleeping in Chief Massasoit‘s bed.

.

The Tragedy of Julius Ceasar

Almost everyone with European ancestors is related to everyone else within the last 2000 years. Remember the king was was ruined by his promise to pay 1 grain of rice of the first chessboard square, 2 on the second, 3 on the third …. 2^62 possible ancestors = 4,611,686,018,427,390,000. ( or 4.6 Quintillion) While Genvissa, the daughter of Claudius who married a Silurian king, was invented by Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1100 – c. 1155), and this lineage includes Old King Cole, we are all kin. We know these Romans from I Claudius and many other stories. This line has Gaelic Kings of every variety, Welsh, Irish, and Scot and famous cameos including St. Patrick, St. Columba and Macbeth. (See my post Marcus Antonius)

62nd G – Marcus Antonius (14 Jan 83 BC – 1 Aug 30 BC) (Wikipedia), Mark Antony was a friend, and cousin, of Gaius Julius Caesar, although after Caesar’s assassination he stopped praising Caesar. Mark Antony had a falling out with Octavian (Augustus) after the Second Triumvirate split up and he ended up in Egypt.

Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1100 – c. 1155) invented much of the descent from Marcus Antonius to Gaelic Kings

Marc Antony: Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears; I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after them, The good is oft interred with their bones; So let it be with Caesar.

Marc Antony: This was the noblest Roman of them all. All the conspirators save only he, did what they did in envy of great Caesar. He only, in a general honest thought, and common will for all, made one of them. His life was gentle, and the elements so mixed in him that the nature might stand up and say to all the world, “This was a man.”

Marc Antony: [to Caesar’s dead body] O pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth / That I am meek and gentle with these butchers.

Marc Antony: [repeated several times, about Caesar] Yet Brutus says he was ambitious/ And Brutus is an honorable man.

.

Macbeth

This is the same genealogy by Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1100 – c. 1155) that links us with Marcus Antonius above. Our immigrant ancestor in this line was 12th G – Major Danyell BROADLEY de West Morton (1589 – 1641)

31st G – MALCOLM II of Alba (Wikipedia) was born about 954 in Scotland. He died on 25 Nov 1034 in Glammys Castle, Angus, Scotland, killed by his kinsman. He was the last king of the house of MacAlpin. He was buried in Isle of Iona, Scotland. Malcolm married a daughter of Sigurd , an Irishwoman from Ossory. They had the following children:

i. Bethoc (Beatrice) , heiress of Scone

ii. Doda Olith of Thora , Princess of Scotland

Malcolm was King of Scotland from 1005 to 1034, the first to rule over an extent of land roughly corresponding to much of modern Scotland. Malcolm succeeded to the throne after killing his predecessor, Kenneth III, and allegedly secured his territory by defeating a Northumbrian army at the battle of Carham (c. 1016); he not only confirmed the Scotish hold over the land between the rivers Forth and Tweed, but also secured Strathclyde about the same time. Eager to secure the royal succession for his daughter’s son Duncan, he tried to eliminmate possible royal claimants; but MacBeth, with royal connections to both Kenneth II and Kenneth III, survived to challenge the succession.

Máel Coluim mac Cináeda (Modern Gaelic: Maol Chaluim mac Choinnich, known in modern anglicized regnal lists as Malcolm II; died 25 Nov 1034), was King of the Scots from 1005 until his death. He was a son of Cináed mac Maíl Coluim; the Prophecy of Berchán says that his mother was a woman of Leinster and refers to him as Máel Coluim Forranach, “the destroyer”.

To the Irish annals which recorded his death, Máel Coluim was ard rí Alban, High King of Scotland. In the same way that Brian Bóruma, High King of Ireland, was not the only king in Ireland, Máel Coluim was one of several kings within the geographical boundaries of modern Scotland: his fellow kings included the king of Strathclyde, who ruled much of the southwest, various Norse-Gael kings of the western coasts and the Hebrides and, nearest and most dangerous rivals, the Kings or Mormaers of Moray. To the south, in the kingdom of England, the Earls of Bernicia and Northumbria, whose predecessors as kings of Northumbria had once ruled most of southern Scotland, still controlled large parts of the southeast.

30th G – Doda OLITH of Thora was born about 986 in Scotland. She died on 25 Nov 1034. Doda married (1) Findleach MacRory of Moray “Synell” (Wikipedia), Lord of Glammis, Mórmaer of Moray in 1004. Findleach was born about 982 in Scotland. He died in 1004/1005 in Scotland.

They had the following children:

i MacBeth (Maelbeatha) , King of Scotland (Wikipedia) – Mac Bethad mac Findlaích (Modern Gaelic: MacBheatha mac Fhionnlaigh,anglicized as Macbeth, and nicknamed Rí Deircc, “the Red King”; died 15 August 1057) was King of the Scots (also known as the King of Alba, and earlier as King ofMoray and King of Fortriu) from 1040 until his death. He is best known as the subject of William Shakespeare’s tragedy Macbeth and the many works it has inspired, although the play presents a highly inaccurate, almost outright fabrication of his reign and personality.

The Life and Death of King John

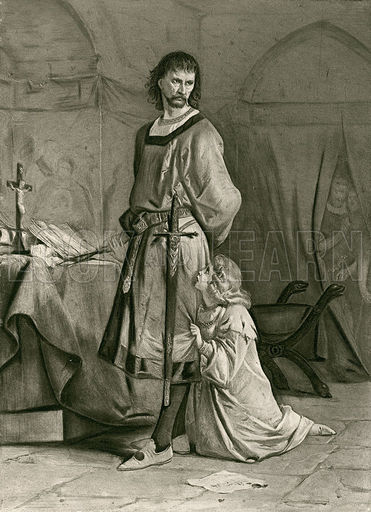

Hubert de BURGH, Alex’s 25th great grandfather in the Miner line and 11th great grandfather of our immigrant ancestor Elizabeth LYND was a character in Shakespeare’s King John. See my post Henry I of France for all 31 generations to the present day. This one was especially fun for me because it ends with 11 generations of Miners.

After John captured his nephew Arthur of Brittany, niece Eleanor and their allies in 1202, de Burgh was made their jailor.

There are several accounts of de Burgh’s actions as jailor, including complicity in Arthur’s death and an account that the king ordered de Burgh to blind Arthur, but that de Burgh refused. This account was used by Shakespeare in his play King John. The truth of these accounts has not been verified, however. For some reason, Shakespeare makes Herbert acitizen of Angers in France and later a follower of King John

The play begins with King John receiving an ambassador from France, who demands, on pain of war, that he renounce his throne in favor of his nephew, Arthur, whom the French King, Philip, believes to be the rightful heir to the throne.

John adjudicates an inheritance dispute between Robert Falconbridge and his older brother Philip the Bastard, during which it becomes apparent that Philip is the illegitimate son of King Richard I. Queen Eleanor, mother to both Richard and John, recognises the family resemblance and suggests that he renounce his claim to the Falconbridge land in exchange for a knighthood. John knights the Bastard under the name Richard.

After various alliances and accusations, war breaks out; and Arthur is captured by the English. John orders Hubert to kill Arthur. Hubert finds himself unable to kill Arthur. John’s nobles urge Arthur’s release. John agrees, but is wrong-footed by Hubert’s announcement that Arthur is dead. The nobles, believing he was murdered, defect to Louis’ side. The Bastard reports that the monasteries are unhappy about John’s attempt to seize their gold. Hubert has a furious argument with John, during which he reveals that Arthur is still alive. John, delighted, sends him to report the news to the nobles.

Arthur dies jumping from a castle wall. (It is open to interpretation whether he deliberately kills himself or just makes a risky escape attempt.) The nobles believe he was murdered by John, and refuse to believe Hubert’s entreaties.

Leaving out details not related to Hubert, John’s former noblemen swear allegiance to Philip’s son, Louis. War breaks out with substantial losses on each side. Hubert is on hand when John is poisoned by a disgruntled monk and he informs the Bastard. The English nobles swear allegiance to John’s son Prince Henry, and the Bastard reflects that this episode has taught that internal bickering could be as perilous to England’s fortunes as foreign invasion.

The Life and Death of King John

Act IV. Scene I.

Northampton. A Room in the Castle.

.

Enter HUBERT and Two Attendants

Hub. Heat me these irons hot; and look thou stand

Within the arras: when I strike my foot

Upon the bosom of the ground, rush forth, 5

And bind the boy which you shall find with me

Fast to the chair: be heedful. Hence, and watch.

First Attend. I hope your warrant will bear out the deed.

Hub. Uncleanly scruples! fear not you: look to ’t. [Exeunt Attendants.]

Young lad, come forth; I have to say with you. 10Enter ARTHUR.

Arth. Good morrow, Hubert.

Hub. Good morrow, little prince.

Arth. As little prince,—having so great a title

To be more prince,—as may be. You are sad. 15

Hub. Indeed, I have been merrier.

Arth. Mercy on me!

Methinks nobody should be sad but I:

Yet I remember, when I was in France,

Young gentlemen would be as sad as night, 20

Only for wantonness. By my christendom,

So I were out of prison and kept sheep,

I should be as merry as the day is long;

And so I would be here, but that I doubt

My uncle practises more harm to me: 25

He is afraid of me, and I of him.

Is it my fault that I was Geffrey’s son?

No, indeed, is ’t not; and I would to heaven

I were your son, so you would love me, Hubert.

Hub. [Aside.] If I talk to him with his innocent prate 30

He will awake my mercy which lies dead:

Therefore I will be sudden and dispatch.

Arth. Are you sick, Hubert? you look pale to-day:

In sooth, I would you were a little sick,

That I might sit all night and watch with you: 35

I warrant I love you more than you do me.

Hub. [Aside.] His words do take possession of my bosom.

Read here, young Arthur. [Showing a paper.

[Aside.] How now, foolish rheum!

Turning dispiteous torture out of door! 40

I must be brief, lest resolution drop

Out at mine eyes in tender womanish tears.

Can you not read it? is it not fair writ?

Arth. Too fairly, Hubert, for so foul effect.

Must you with hot irons burn out both mine eyes? 45

Hub. Young boy, I must.

Arth. And will you?

Hub. And I will.

Arth. Have you the heart? When your head did but ache,

I knit my handkercher about your brows,— 50

The best I had, a princess wrought it me,—

And I did never ask it you again;

And with my hand at midnight held your head,

And like the watchful minutes to the hour,

Still and anon cheer’d up the heavy time, 55

Saying, ‘What lack you?’ and, ‘Where lies your grief?’

Or, ‘What good love may I perform for you?’

Many a poor man’s son would have lain still,

And ne’er have spoke a loving word to you;

But you at your sick-service had a prince. 60

Nay, you may think my love was crafty love,

And call it cunning: do an if you will.

If heaven be pleas’d that you must use me ill,

Why then you must. Will you put out mine eyes?

These eyes that never did nor never shall 65

So much as frown on you?

Act IV scene i Shakespeare NYC — Arthur [Miriam Lipner] pleads with Hubert. [Joseph Small] Hubert: “Hold you tongue.” Arthur: “Let me not hold my tongue. Let me not, Hubert,/Or Hubert, if you will, cut out my tongue,/So I may keep my eyes. O spare mine eyes,/Though to no use but still to look on you.” Hubert cannot bear to harm the boy and secretly conveys him to another part of the Tower.

Hub. I have sworn to do it;

And with hot irons must I burn them out.

Arth. Ah! none but in this iron age would do it!

The iron of itself, though heat red-hot, 70

Approaching near these eyes, would drink my tears

And quench this fiery indignation

Even in the matter of mine innocence;

Nay, after that, consume away in rust,

But for containing fire to harm mine eye. 75

Are you more stubborn-hard than hammer’d iron?

An if an angel should have come to me

And told me Hubert should put out mine eyes,

I would not have believ’d him; no tongue but Hubert’s.

Hub. [Stamps.] Come forth. 80Re-enter Attendants, with cord, irons, &c.

Do as I bid you do.

Arth. O! save me, Hubert, save me! my eyes are out

Even with the fierce looks of these bloody men.

Hub. Give me the iron, I say, and bind him here. 85

Arth. Alas! what need you be so boisterous-rough?

I will not struggle; I will stand stone-still.

For heaven’s sake, Hubert, let me not be bound!

Nay, hear me, Hubert: drive these men away,

And I will sit as quiet as a lamb; 90

I will not stir, nor wince, nor speak a word,

Nor look upon the iron angerly.

Thrust but these men away, and I’ll forgive you,

Whatever torment you do put me to.

Hub. Go, stand within: let me alone with him. 95

First Attend. I am best pleas’d to be from such a deed. [Exeunt Attendants.

Arth. Alas! I then have chid away my friend:

He hath a stern look, but a gentle heart.

Let him come back, that his compassion may

Give life to yours. 100

Hub. Come, boy, prepare yourself.

Arth. Is there no remedy?

Hub. None, but to lose your eyes.

Arth. O heaven! that there were but a mote in yours,

A grain, a dust, a gnat, a wandering hair, 105

Any annoyance in that precious sense;

Then feeling what small things are boisterous there,

Your vile intent must needs seem horrible.

Hub. Is this your promise? go to, hold your tongue.

Arth. Hubert, the utterance of a brace of tongues 110

Must needs want pleading for a pair of eyes:

Let me not hold my tongue; let me not, Hubert:

Or Hubert, if you will, cut out my tongue,

So I may keep mine eyes: O! spare mine eyes,

Though to no use but still to look on you: 115

Lo! by my troth, the instrument is cold

And would not harm me.

Hub. I can heat it, boy.

Arth. No, in good sooth; the fire is dead with grief,

Being create for comfort, to be us’d 120

In undeserv’d extremes: see else yourself;

There is no malice in this burning coal;

The breath of heaven hath blown his spirit out

And strew’d repentant ashes on his head.

Hub. But with my breath I can revive it, boy. 125

Arth. An if you do you will but make it blush

And glow with shame of your proceedings, Hubert:

Nay, it perchance will sparkle in your eyes;

And like a dog that is compell’d to fight,

Snatch at his master that doth tarre him on. 130

All things that you should use to do me wrong

Deny their office: only you do lack

That mercy which fierce fire and iron extends,

Creatures of note for mercy-lacking uses.

Hub. Well, see to live; I will not touch thine eyes 135

For all the treasure that thine uncle owes:

Yet am I sworn and I did purpose, boy,

With this same very iron to burn them out.

Arth. O! now you look like Hubert, all this while

You were disguised. 140

Hub. Peace! no more. Adieu.

Your uncle must not know but you are dead;

I’ll fill these dogged spies with false reports:

And, pretty child, sleep doubtless and secure,

That Hubert for the wealth of all the world 145

Will not offend thee.

Arth. O heaven! I thank you, Hubert.

Hub. Silence! no more, go closely in with me:

Much danger do I undergo for thee. [Exeunt.]

Back to the Real Hubert de Burgh

Hubert de BURGH, 1st Earl of Kent (c. 1160 – before 5 May 1243) was Justiciar of England and Ireland, and one of the most influential men in England during the reigns of John and Henry III.

De Burgh was born into a modest, minor landowning family from East Anglia and, therefore, had to work twice as hard to make a name for himself as opposed to his counterparts in the nobility. He was the son of Walter de Burgh of Burgh Castle, Norfolk. Hubert seems to have been a staunch supporter of John, youngest son of King Henry II, even before he became king, acting as chamberlain of the prince’s household. When John succeeded his brother, Richard I, to the throne in 1199, Hubert was upgraded to royal chamberlain, a position that involved being constantly within the presence of the king. Therefore, it is no surprise that his influence rapidly grew.

In his early adulthood Hubert vowed to rescue the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the holy land, so he set off for Jerusalem on the Third Crusade. Hubert is one of the possible de Burgh’s that received the coat of arms, it is said that Richard I dipped his finger in the blood of a slain Saracen king, put a red cross on the gold shield of de Burgh, and said “for your bravery this will be your crest”, and it is also said that he uttered the words “a cruce salus” which became the family motto.

In the early years of John’s reign de Burgh was greatly enriched by royal favour. While John was away in France pressing his claim to his territories there, Hubert was left in charge of the Welsh marches and was given several other important posts. He received the honour of Corfe in 1199 and three important castles in the Welsh Marches in 1201 (Grosmont Castle, Skenfrith Castle, and Llantilio Castle). He was also High Sheriff of Dorset and Somerset (1200), Berkshire (1202) and Herefordshire (1215), and castellan of Launceston and Wallingford castles. He was also appointed Constable of Dover Castle, and also given charge of Falaise, in Normandy. He is cited as having been appointed a Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports by 1215.

After John captured his nephew Arthur of Brittany, niece Eleanor and their allies in 1202, de Burgh was made their jailor.

There are several accounts of de Burgh’s actions as jailor, including complicity in Arthur’s death and an account that the king ordered de Burgh to blind Arthur, but that de Burgh refused.

In any case de Burgh retained the king’s trust, and in 1203 Hubert had departed to France to aid with the wars and would remain there for several years.. He was given charge of the great castles at Falaise in Normandy and Chinon, in Touraine. The latter was a key to the defence of the Loire valley. After the fall of Falaise de Burgh held out while the rest of the English possessions fell to the French. Chinon was besieged for a year, and finally fell in June, 1205, Hubert being badly wounded while trying to evade capture.

During Hubert’s two years of captivity, his influence waned within England and many of his lands and positions were either given away or absorbed by the crown. Finally, in 1207, King John ransomed Hubert and quickly returned him to royal favor, helping him reacquire most of what he had lost during his captivity. he acquired new and different lands and offices. These included the castles of Lafford and Sleaford, and the shrievalty of Lincolnshire (1209–1214). Probably, however, de Burgh spent most of his time in the English holdings in France, where he was seneschal of Poitou.

Over the following years, Hubert would continue to build his wealth, power and influence, acting as a sheriff and gaining experience as a justiciar, a task he would be remembered for. It is believed that Hubert remained completely loyal to John when the magnates rebelled and forced him to sign the Magna Carta in 1215..

The Magna Carta mentions him as one of those who advised the king to sign the charter, and he was one of the twenty-five sureties of its execution. John named him Chief Justiciar in June 1215. and appointed him High Sheriff of Surrey (1215), High Sheriff of Herefordshire (1215), High Sheriff of Kent (1216–1222), and Governor of Canterbury Castle. Soon afterwards he was appointed Governor of the castles of Hereford, Norwich and Oxford.

De Burgh played a prominent role in the defence of England from the invasion of Louis of France, the son of Philippe II who later became Louis VIII. Louis’ first objective was to take Dover Castle, which was in de Burgh’s charge. The castle withstood a lengthy siege in the summer and autumn of 1216, and Louis withdrew. The next summer Louis could not continue without reinforcements from France. De Burgh gathered a small fleet which defeated a larger French force at the Battle of Dover and Battle of Sandwich, and ultimately led to the complete withdrawal of the French from England.

During the new minority regime, Hubert no doubt possessed a great amount of influence as justiciar, but with men such as William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke (regent to the underage king Henry III); the papal legate Pandulf; and Peter des Roches, bishop of Winchester, in the mix, de Burgh was most certainly kept in check. However, the aged Pembroke died (1219); Pandulf left for Rome (1221); and des Roches left for an extended crusade (1223).

These departures left de Burgh as the undisputed top man in Henry’s government and in effect, the acting regent. During the next eight years or so, de Burgh acted as justiciar, military commander (taking part in the Welsh expeditions, with mixed results) and played a role in the keeping of the royal exchequer. He was appointed High Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk (1216–1225) and High Sheriff of Kent (1223–1226). De burgh accumulated much wealth as a result and was rewarded for his services even further by being created Earl of Kent (1227).

When Henry III came of age in 1227 de Burgh was made lord of Montgomery Castle in the Welsh Marches and Earl of Kent. He remained one of the most influential people at court. On 27 April 1228 he was named Justiciar for life.

Unfortunately, De Burgh’s success would be fairly short-lived. Bishop Des Roches returned to England (1231) and joined forces with his nephew Peter de Rivallis in an effort to bring down the justiciar, accusing him of a number of crimes, including appointing Italians to English posts. The king, at first, defended De Burgh, but soon enough, Hubert was stripped of his offices and most of his lands and forced to take sanctuary in various cathedrals.

In 1233, De Burgh was forced to beg the king’s mercy, which he was given, and was restored to some of his lands. The following year, he was officially pardoned, but his days of power were clearly at an end. Hubert’s rivals made several more attempts to completely eliminate the justiciar, but De Burgh was able to live out the rest of his life quietly, dying in 1243 at the age of 82 or 83 in Banstead, Surrey, England and was buried at the church of the Black Friars in Holborn.

Over his long life, De Burgh had demonstrated the powers of royal favor and how they could make or break a man. In the end, though able to live out his life peacefully, Hubert remained broken.

.

Henry IV Part 1

Alex’s 14th Great Grandfather and Francis MARBURY’s great grandfather William MARBURY, of Lowick, Northampton, esquire, was born ca 1445-53. That he was a man of considerable social standing and prestige in Northampton county is indicated by the fact that he is first mentioned in 1473 as an executor of the will of John Stafford,1st Earl of Wiltshire, the youngest son of Humphrey Stafford, the powerful 1st Duke of Buckingham.

William Marbury married about this time into the prominent family of Blount. His wife Anne BLOUNT, daughter of Sir Thomas BLOUNT and Agnes HAWLEY, was niece of Sir Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy, K.G., who in 1467 had married Anne Neville, the widow of Humphrey Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. The character of Westmorland in William Shakespeare’s plays Henry IV, Part 1, Henry IV, Part 2, and Henry V is based on Anne’s father Ralph de Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland.

In the opening scene of Henry IV, Part 1, Westmorland is presented historically as an ally of King Henry IV against the Percys, and in the final scenes of the play as being dispatched to the north of England by the King after the Battle of Shrewsbury to intercept the Earl of Northumberland.

In Act IV of Henry IV, Part 2, Westmorland is portrayed historically as having been principally responsible for quelling the Percy rebellion in 1405 by Archbishop Scrope almost without bloodshed by successfully parleying with the rebels on 29 May 1405 at Shipton Moor.

However in Henry V Westmorland is unhistorically alleged to have resisted the arguments made in favour of war with France by Archbishop Chichele in the Parliament which began at Leicester on 30 April 1414.

.

Henry IV Part 2

Sir Henry BOYNTON of Acklam, William BOYNTON‘s 7th great grandfather, was beheaded on 2 Jul 1405 in Berwick-on-Tweed-Castle, Yorkshire, England. He had joined the Northern Rebellion, an insurrection led by the Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, Thomas Mowbray, and Richard le Scrope Archbishop of York. against Henry IV portrayed in Henry IV Part 2.

Sir Henry was young and unexperianced, probably in his late twenties, when he succeeded his grandfather Sir Thomas in 1402 and inherited the Boynton family fortune. He was suspected to be in the interest of Henry (Percy) Earl of Northumberland and his son Henry Hotspur, who had taken arms against the King, Henry IV, for in the fourth year of his reign, when the battle of Shrewsbury (Jul 21 1403) was fought. (See Henry IV Part 1 where Hotspur was slain)

John Wockerington, Gerald Heron and John Mitford were commissioned to tender an oath to this Henry de Boynton and others, to be true to the King and renounce Henry, Earl of Northumberland and his adherents

Yet two years after the Percys defeat at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, Sir Henry was involved in the Northern Rising against Henry IV.

In 1405 Northumberland, joined by Lord Bardolf, again took up arms against the King. The rising was doomed from the start due to Northumberland’s failure to capture Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland. Scrope, together with Thomas de Mowbray, 4th Earl of Norfolk, and Scrope’s nephew, Sir William Plumpton, had assembled a force of some 8000 men on Shipton Moor on 27 May, but instead of giving battle Scrope parleyed with Westmorland, and was tricked into believing that his demands would be accepted and his personal safety guaranteed. (For Shakespeare’s take on this meeting in Henry IV Part 2 Act IV Scenes i-iii, see my post Shakespearean Ancestors.)

Once their army had disbanded on 29 May, Scrope and Mowbray were arrested and taken to Pontefract Castle to await the King, who arrived at York on 3 June. The King denied them trial by their peers, and a commission headed by the Earl of Arundel and Sir Thomas Beaufort sat in judgment on Scrope, Mowbray and Plumpton in Scrope’s own hall at his manor of Bishopthorpe, some three miles south of York.

The Chief Justice, Sir William Gascoigne, refused to participate in such irregular proceedings and to pronounce judgment on a prelate, and it was thus left to the lawyer Sir William Fulthorpe to condemn Scrope to death for treason. Scrope, Mowbray and Plumpton were taken to a field belonging to the nunnery of Clementhorpe which lay just under the walls of York, and before a great crowd were beheaded on 8 June 1405, Scrope requesting the headsman to deal him five blows in remembrance of the five wounds of Christ.

Although Scrope’s participation in the Percy rebellion of 1405 is usually attributed to his opposition to the King’s proposal to temporarily confiscate the clergy’s landed wealth, his motive for taking an active military role in the rising continues to puzzle historians.

Pope Innocent VII excommunicated all those involved in Scrope’s execution. However Archbishop Arundel failed to publish the Pope’s decree in England, and in 1407 Henry IV was pardoned by Pope Gregory XII

Meanwhile Sir Henry fled to Berwick Castle. Henry de Boynton was beheaded on 2 Jul 1405 along with six other knights who were captured when the castle at Berwick upon Tweed was taken. Henry Percy escaped into Scotland.

A mandate was issued to the Mayor of Newcastle-on-Tyne to receive the head of Henry Boynton, “chivaler,” [Archaic. a knight.] and to place it on the bridge of the town to stay there as long as it would last, but within a month another mandate* was issued to the Mayor to take down the head, where it was lately placed by the King’s command, and to deliver it to Sir Henry’s wife for burial.

After the insurrection had been crushed Henry IV inserted into the record of Parliament the perfidy of Henry Percy. Among the indictments was the claim that Henry Percy had appointed Henry Boynton to negotiate for him with the kings of Scotland and France. Whether he engaged in negotiations or was only appointed to engage in negotiations is not clear from the text. But it suggests a close — if surreptitious — working relationship. A relationship that cost Henry Boynton his head.

Sir Henry’s property, the manor of Acklam in Cleveland, with all members being forfeited and in the King’s hands, was granted to Roger de Thornton, Mayor of Newcastle-on-Tyne but in the following August a grant was made for life to Elizabeth, late the wife of Henry Boynton, who had not wherewithal to maintain herself and six children or to pay her late husband’s debts, of the towns of Roxby and Newton, late the said Henry’s and forfeited to the King, on account of his rebellion, to hold to the value of £20 yearly, and there was granted to her also all his goods, likewise forfeited, to the value of £20, and she must answer for any surplus.

The king did provide for Henry’s mother and wife by setting aside some of the Boynton land to maintain them, but that land returned to the king when they died. Henry’s second son William petitioned the king in 1424 for the return of the family land, and it was returned by 1427. For more on the Boyntons, including William’s petitions, see his 7th great grandson’s page William BOYNTON (1580 – 1615) father of two American immigrants William and John.

The Percy Rebellion (1402–1408) was three attempts by the Percy family and their allies to overthrow Henry IV:

- Battle of Shrewsbury (1403). King Henry IV defeated a rebel army led by Henry Hotspur Percy who had allied with the Welsh rebel Owain Glyndŵr. Percy was killed in the battle by an arrow in his face. [In hand to hand combat with Prince Hall in Henry IV Part I]. Thomas Percy, 1st Earl of Worcester, Sir Richard Venables and Sir Richard Vernon were publicly hanged, drawn and quartered in Shrewsbury on 23 July and their heads publicly displayed. The Earl of Northumberland flees to Scotland.

- Archbishop of York Richard le Scrope lead a failed rebellion in northern England (1405). Scrope and other rebel leaders including Sir Henry BOYNTON are executed. The Earl of Northumberland again flees to Scotland.

- Battle of Bramham Moor (1408). The Earl of Northumberland invades Northern England with Scottish and Northumbrian allies but is defeated and killed in battle.

Henry IV Part 2 Act IV, Scenes i-iii

In Gaultree Forest in Yorkshire, the leaders of the rebel army–the Archbishop of York, Mowbray, and Hastings–have arrived with their army. The Archbishop tells his allies he has received a letter from Northumberland in which he says he will not be coming to their aid.

A soldier, returning to the camp from a scouting mission, reports that King Henry IV’s approaching army is now barely a mile away. The army is being led by Prince John, the king’s younger son; the king, who is sick, is still at Westminster. The scout is immediately followed by the Earl of Westmoreland, an ally of King Henry who has been sent as a messenger. Westmoreland accuses the Archbishop of improperly using his religious authority to support rebellion; the Archbishop replies that he did not want to, but he felt he had no choice, since King Henry was leading the country into ruin and the rebels could not get their complaints addressed. Westmoreland tells the rebels that Prince John has been given full authority to act in the king’s name and is willing to grant their demands if they seem reasonable. The Archbishop gives Westmoreland a list of the rebels’ demands, and Westmoreland leaves to show it to Prince John.

While the rebels wait for Westmoreland to return, Mowbray voices his fear that, even if they do make peace, the royal family will only be waiting for an opportunity to have them killed. However, Hastings and the Archbishop are sure that his fears are groundless.

Westmoreland returns and brings the rebels back with him to the royal camp to speak with Prince John. The prince says that he has looked over the demands and that they seem reasonable; he will grant all the rebels’ requests. If they agree, he says, they should discharge their army and let the soldiers go home.

Very pleased, the rebel leaders send messengers to tell their soldiers that they can go home. They and Prince John drink together and make small talk about the upcoming peace. However, as soon as word comes from the rebels’ messengers that their army has been scattered, Prince John gives an order to arrest Hastings, Mowbray, and the Archbishop as traitors. When they ask how he can be so dishonorable, Prince John answers that he is not breaking his word: he promised to address their complaints, and he will. However, he never promised not to kill the rebels themselves. He then gives orders for the rebels to be taken away and executed.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the forest, one of the departing rebels–Sir John Coleville of the Dale–runs into Falstaff, who has finally made it to the field of battle. Recognizing Falstaff, Coleville surrenders to him. (Most people are now afraid of Falstaff because they falsely believe that he killed the famous rebel Hotspur at the Battle of Shrewsbury.) Prince John enters the scene and Falstaff presents his captive to him. Westmoreland appears to tell the Prince that the army is withdrawing; Prince John sends Coleville off with the other rebels to execution, and he announces he will return to the court in London because he hears his father is very sick. Falstaff heads off to Gloucestershire in order to beg some money from Justice Shallow.

Prince John’s behavior in these scenes is, at best, underhanded and, at worst, tremendously dishonorable. He effectively lies to the rebels, telling Mowbray, Hastings and the Archbishop that he will concede to their demands, and then he reneges on his promise as soon as they have trustingly sent away their troops. The technicality that he uses to justify his action–the fact that he promised to address the rebels’ complaints, not to ensure their safety–seems morally questionable. Prince John seems to go out of his way to convince the rebels that he means them no harm, repeatedly saying things like “Let’s drink together friendly and embrace / That all their eyes may bear the tokens home / Of our restored love and amity” (63-65). That Hastings, Mowbray, and the Archbishop would have taken this as a promise of forgiveness seems obvious.

Prince John comes across as a much more treacherous character than any of the rebels over whom he claims moral authority. However, if we begin by assuming, as many during the Middle Ages did, that the king and the royal family are always right and have the authority of God himself behind them, then anyone who rises against them is clearly in the wrong. The royal family, thus, has the right to defeat them by any means necessary.

This line of thinking is related to the idea of the “divine right” of kings. It is an idea with obvious political value for rulers and one that was popular in the Middle Ages; the Renaissance was just beginning to question this assumption. It is obvious that at least some of King Henry’s followers subscribe to this idea. When the Archbishop challenges Prince John’s duplicity by asking, “Is this proceeding just and honorable?” Westmoreland replies by asking, “Is your assembly so?” This is the only answer that either he or John makes to the rebels’ accusations that Prince John has broken his oath. Answering the questions only with another question, Westmoreland implies that Prince John’s behavior is not wrong because it has corrected a previous wrong (i.e., “two wrongs make a right”).

This concept of honor may be good enough for Prince John, and it may have been what some of Shakespeare’s audience–including his ruler, Queen Elizabeth–wanted to hear. Shakespeare, however, seems to have been ambivalent about it; he has Falstaff voice his reservations about Prince John’s behavior in his closing speech in IV.iii. In typical Falstaff style, he goes off into a very long, complex, and witty speech about a seemingly trivial topic–this time, wine–and expands it into a discussion of abstract truths that apply to the situation at hand.

In praising the virtue wine has in making men witty, Falstaff brings forth the virtues of a value system different from that of the king and his followers. He criticizes Prince John, in a somewhat worried tone, wishing that Prince John had “wit,” for it would be “better than your dukedom. Good faith,” he goes on, “this same sober-blooded boy doth not love me, not a man cannot make him laugh… There’s never none of these demure boys come to any proof… They are generally fools and cowards” (84-93). Falstaff humorously blames Prince John’s defects on his refusal to drink wine, but he also makes a valid criticism of Prince John’s frightening lack of a sense of humor and strange version of “honor,” which seems to be utterly lacking in human compassion. Falstaff knows, too, where Prince John got these bad qualities: from the leader of the state himself, King Henry IV. Even Prince Hal, he adds, is only valiant because “the cold blood he inherited of his father he hath… tilled, with excellent endeavor of drinking”

.

Henry VI Part 3

Everard “Greenleaf” DIGBY died 29 Mar 1461 at the Battle of Towton, West Riding, Yorkshire, England.

He was killed, together with his three brothers, fighting for the house of Lancaster. His seven sons including Everard DIGBY Esq. fought for Henry VII at the battle of Bosworth Field 22 August 1485. This time, the Digbys were on the winning side.

The Battle of Towton was fought during the English Wars of the Roses on 29 March 1461, near the village of the same name in Yorkshire. It was the “largest and bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil”. According to chroniclers, more than 50,000 soldiers from the Houses of York and Lancaster fought for hours amidst a snowstorm on that day, which was a Palm Sunday. A newsletter circulated a week after the battle reported that 28,000 died on the battlefield. The engagement brought about a monarchical change in England—Edward IV displaced Henry VI as King of England, driving the head of the Lancastrians and his key supporters out of the country.

Henry was weak in character and mentally unsound. His ineffectual rule had encouraged the nobles’ schemes to establish control over him, and the situation deteriorated into a civil war between the supporters of his house and those of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York. After the Yorkists captured Henry in 1460, the English parliament passed an Act of Accord to let York and his line succeed Henry as king. Henry’s consort, Margaret of Anjou, refused to accept the dispossession of her son’s right to the throne and, along with fellow Lancastrian malcontents, raised an army. Richard of York was killed at the Battle of Wakefield and his titles, including the claim to the throne, passed to his eldest son Edward. Nobles, who were previously hesitant to support Richard’s claim to the throne, regarded the Lancastrians to have reneged on the Act—a legal agreement—and Edward found enough backing to denounce Henry and declare himself king. The Battle of Towton was to affirm the victor’s right to rule over England through force of arms.

On reaching the battlefield, the Yorkists found themselves heavily outnumbered. Part of their force under John de Mowbray, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, had yet to arrive. The Yorkist leader Lord Fauconberg turned the tables by ordering his archers to take advantage of the strong wind to outrange their enemies. The one-sided missile exchange—Lancastrian arrows fell short of the Yorkist ranks—provoked the Lancastrians into abandoning their defensive positions. The ensuing hand-to-hand combat lasted hours, exhausting the combatants. The arrival of Norfolk’s men reinvigorated the Yorkists and, encouraged by Edward, they routed their foes. Many Lancastrians were killed while fleeing; some trampled each other and others drowned in the rivers. Several who were taken as prisoners were executed.

The power of the House of Lancaster was severely reduced after this battle. Henry fled the country, and many of his most powerful followers were dead or in exile after the engagement, letting Edward rule England uninterrupted for nine years, before a brief restoration of Henry to the throne. Later generations remembered the battle as depicted in William Shakespeare‘s dramatic adaptation of Henry’s life—Henry VI, Part 3, Act 2, Scene 5.

In the play the Yorkists regroup, and at the Battle of Towton, Clifford is killed and the Yorkists romp to victory. Following the battle, Edward is proclaimed king, George is proclaimed Duke of Clarence and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, although he complains to Edward that this is an ominous dukedom. Edward and George then leave the court, and Richard reveals to the audience his own machinations to rise to power and take the throne from his brother, although, as yet, he is unsure how exactly he might go about it.

Whereas 1 Henry VI deals with loss of England’s French territories and the political machinations leading up to the Wars of the Roses, and 2 Henry VI focuses on the King’s inability to quell the bickering of his nobles, and the inevitability of armed conflict, 3 Henry VI deals primarily with the horrors of that conflict, with the once ordered nation thrown into chaos and barbarism as families break down and moral codes are subverted in the pursuit of revenge and power.

Henry VI, Part 3 has more battle scenes (four on stage, one reported) than any other of Shakespeare’s plays. Critics have cited the amount of violence as indicative of Shakespeare’s artistic immaturity and inability to handle his chronicle sources, especially when compared to the more nuanced and far less violent second historical tetralogy (Richard II, 1 Henry IV, 2 Henry IV and Henry V). Writing in 1605, Ben Jonson commented in The Masque of Blackness that showing battles on stage was only “for the vulgar, who are better delighted with that which pleaseth the eye, than contenteth the ear.”

Recent scholarship has tended to look at the play as being a more complete dramatic text, rather than a series of battle scenes loosely strung together with a flimsy narrative. Some critics now argue that the play “juxtaposes the stirring aesthetic appeal of martial action with discursive reflection on the political causes and social consequences.”

Richard III

Middleham Castle in Wensleydale, in North Yorkshire, was built by Robert FITZRANDOLPH, 3rd Lord of Middleham and Spennithorne, commencing in 1190. Robert’s granddaughter Mary (aka Mary Tailboys) was the heiress of Middleham. When she married Robert Neville ( ~1240 – 1271), the castle passed to to the Neville family. The House of Neville became one of the two major powers in northern England along with the House of Percy and played a central role in the Wars of the Roses.

Middleham was built near the site of an earlier motte and bailey castle. Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, known to history as the “Kingmaker” and a leading figure in the Wars of the Roses was master of the castle.

For the Fitz Randolph lineage back to RICHARD I Duke of Normandy and the generations of the House of Neville – From Mary Fitz Randolf to Edward IV and Richard III , see Edward FITZ RANDOLPH Sr.‘s page. Our immigrant ancestor was Edward FITZ RANDOLPH

On another family note, Captain Mark HILTON was Edward IV‘s second great grandson

Middleham Castle is an impressive ruin, and the sense of its original strength and grandeur remains.

Following the death of Richard, Duke of York at Wakefield in December 1460, his younger sons, George, Duke of Clarence and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, came into Warwick’s care, and both lived at Middleham with Warwick’s own family. Their brother King Edward IV was imprisoned at Middleham for a short time, having been captured by Warwick in 1469. Following Warwick’s death at Barnet in 1471 and Edward’s restoration to the throne, his brother Richard married Anne Neville, Warwick’s younger daughter, and made Middleham his main home. Their son Edward was also born at Middleham and later also died there.

Richard ascended to the throne as King Richard III, but spent little or no time at Middleham in his two-year reign.

.

Henry VIII – All Is True

The play implies, without stating it directly, that the treason charges against the Duke of Buckingham were false and trumped up; and it maintains a comparable ambiguity about other sensitive issues.

Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham was a key character in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, losing his head in Act II and was also Anthony PAYNE’s boss when Payne was bailiff of Hengrave Manor.

Modern scholars believe the play to be a collaboration between William Shakespeare and John Fletcher. The most common delineation of the two poets’ shares in the play is:

- Shakespeare: Act I, scenes i and ii; II,iii and iv; III,ii, lines 1–203 (to exit of King); V,i

- Fletcher: Prologue; I,iii; II,i and ii; III,i, and ii, 203–458 (after exit of King); IV,i and ii; V ii–v; Epilogue.

Shakespeare was well into retirement – we think he retired around 1611 – and this was written in 1613. It’s most likely his last play, but we don’t know. Some say the scenes that are written by Fletcher are creaky. You can see in some scenes it doesn’t have that Shakespearean touch that we are used to. Henry VIII nevertheless has a reputation for visual spectacle.

Henry VIII is believed to have been first performed as part of the ceremonies celebrating the marriage of Princess Elizabeth in 1612–1613, although the first recorded performance was on 29 Jun 1613 at the Globe Theatre. During that performance, a cannon shot employed for special effects ignited the theatre’s thatched roof (and the beams), burning the original building to the ground.

Fifteen years to the day after the fire, on 29 Jun 1628, The King’s Men performed the play again at the Globe. The performance was witnessed by James I’s protege and possible lover, George Villiers, the contemporary Duke of Buckingham, who left halfway through once the play’s Duke of Buckingham was executed. A month later, Villiers was assassinated.

BUCKINGHAM: Nay, Sir Nicholas,

Let it alone; my state now will but mock me.

When I came hither I was Lord High Constable

And Duke of Buckingham; now poor Edward Bohun.

Yet I am richer than my base accusers,

That never knew what truth meant: I now seal it;

And with that blood will make ’em one day groan for’t.

My noble father, Henry of Buckingham,

Who first raised head against usurping Richard,

Flying for succor to his servant Banister,

Being distressed, was by that wretch betrayed,

And without trial fell; God’s peace be with him!

Henry the Seventh succeeding, truly pitying

My father’s loss, like a most royal prince

Restored me to my honors; and out of ruins

Made my name once more noble. Now his son,

Henry the Eighth, life, honor, name, and all

That made me happy, at one stroke has taken

For ever from the world. I had my trial,

And must needs say a noble one; which makes me

A little happier than my wretched father.

Yet thus far we are one in fortunes: both

Fell by our servants, by those men we loved most–

A most unnatural and faithless service.

Heaven has an end in all; yet you that hear me,

This from a dying man receive as certain:

Where you are liberal of your loves and counsels

Be sure you be not loose; for those you make friends

And give your hearts to, when they once perceive

The least rub in your fortunes, fall away

Like water from ye, never found again

But where they mean to sink ye. All good people,

Pray for me! I must now forsake ye; the last hour

Of my long weary life is come upon me.

Farewell!

Steven Waddington as Duke of Buckingham in Showtime’s “The Tudors.” Not Shakespeare or historically accurate, but lots of fun

Our ancestor William PAYNE Sr. was Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham‘s bailiff at the Manor of Hengrave. Under the manorial system a bailiff of the manor represented the peasants to the lord, oversaw the lands and buildings of the manor, collected fines and rents, and managed the profits and expenses of the manor and farm. Bailiffs were outsiders and free men, that is, not from the village. Borough bailiffs would be in charge of the villagers in the town.

William removed from Leicestershire to Suffolk and took up his residence at Hengrave. Carrying with him the use of his grandfather’s Coat of Arms, this came thence forth, in heraldic history to be known as the “Coat and Crest of Leicestershire, and Suffolk, ” and is especially known as belonging to “Payne of Hengrave.”

Buckingham was in attendance at court at the creation of Henry VII’s second son, the future King Henry VIII, as Duke of York on 9 November 1494, and was made a Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1495. In September 1497 he was a captain in the forces sent to quell a rebellion in Cornwall.

According to Davies, as a young man Buckingham played a conspicuous part in royal weddings and the reception of ambassadors and foreign princes, ‘dazzling observers by his sartorial splendour’. At the wedding of Henry VII’s then eldest son and heir Arthur, Prince of Wales, and Catherine of Aragon in 1501, he is said to have worn a gown worth £1500. He was the chief challenger at thetournament held the following day.

At the accession of King Henry VIII, Buckingham was appointed on 23 June 1509, for the day of the coronation only, Lord High Constable, an office which he claimed by hereditary right. He also served as Lord High Steward at the coronation, and bearer of the crown. In 1509 he was made a member of the King’s Privy Council.

According to Davies, in general Buckingham exercised little direct political influence, and was never a member of the King’s inner circle.

Buckingham fell out dramatically with the King in 1510, when he discovered that the King was having an affair with the Countess of Huntingdon, the Duke’s sister and wife of the 1st Earl of Huntingdon. She was taken to a convent sixty miles away. There are some suggestions that the affair continued until 1513. However, he returned to the King’s graces, being present at the marriage of Henry’s sister, served in Parliament and being present at negotiations with Francis I of France and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Buckingham, with his Plantagenet blood and numerous connections by descent or marriage with the rest of the aristocracy, became an object of Henry’s suspicion. During 1520, Buckingham became suspected of potentially treasonous actions and Henry VIII authorized an investigation. The King personally examined witnesses against him, gathering enough evidence for a trial. The Duke was finally summoned to Court in April 1521 and arrested and placed in the Tower. He was tried before a panel of 17 peers, being accused of listening to prophecies of the King’s death and intending to kill the King; however, the King’s mind appeared to be decided and conviction was certain. He was executed on Tower Hill on 17 May.

The office thus becoming vacant by the death of the Duke, William PAYNE lost his place as deputy, and was obliged to retire to private life.

The Duke’s successor Sir Thomas Kytson , however, appointed William Payne’s son Henry to the office of bailiff previously held by the father. Kytson was a wealthy English merchant, sheriff of London, and builder of Hengrave Hall.

Henry Payne became good friends with Sir Thomas and his wife and her third husband John Bourchier, 2nd Earl of Bath. Henry was also counsel for the Earl and Countess of Bath. Hengrave Hall is one of the most magnificent manors from the Tudor period still existing.

Im trying to follow this,however I dont know who Im connected to/somewhere I have John Proctor-from England-Salem Mass.These other people Im also reading about -I dont know if theres a connection.I have John Cobb/#1 marEngland#2 Mass-she was from Mass. I have Salde-mostly from Vt.?Styles Vt.,French,Proctor ,Knight,Moon Vt.???

Janet,

Check this post — https://minerdescent.com/2010/10/26/john-proctor/

Thanks for this! As an anglophile, amateur historian, fan of Richard the III and The Archers, I have found this post to be very interesting!! I love all of the connections that can be made between historical events and our ancestors. Your blog has inspired me to start my own. I am still working on the organization. Trying to put the ancestry of thousands of ancestors into one

blog is formidable and I hope I get it worked out someday. I, too, have a Shakespearean connection through the Kings of Scotland in particular one named Macbeth! I visited the little green isle of Iona where he was buried in June of 2011. My blog is still in its infancy, but please take a look, http://www.gransfamilyhistory.com.

Hi Teresa,

Thanks for the kind words. I originally planned to “trace each branch back to their arrival in America”, but having players in the game makes English history and Shakespeare’s histories more fun (Even when the heads that roll are our relatives!)

I also have relatives who were captured at the Battle of Dunbar, held at Durham Cathedral and then transported as prisoners of war to work in the Saugus Iron Works in Massachusetts. They didn’t get on well with their Puritan overseers. See my post https://minerdescent.com/2012/07/24/scottish-prisoners/

Good luck with your blog, your grand baby looks very sweet.

Mark

My favorite historical novel about Richard the Third is, The Sunne in Splendour, by Sharon Kay Penman, an excellent read! I am also a descendant of Robert the Bruce and William Marshall, whom you discuss above. I see that we also share Elder John Strong as an ancestor. I have a lot of Colonial ancestors that lived in Massachusetts Bay so we probably have other connections there as well.

Hi Teresa,

I enjoyed Penman’s novels too. It’s been many years so maybe it’s time to re-read. Did you know that when the manuscript to The Sunne in Splendour, her first book, was stolen she started again and rewrote the whole thing? I enjoyed her Welch Princes trilogy because that history was all new to me.

Cheers! Mark

Pingback: William Boynton | Miner Descent

Pingback: Favorite Posts 2013 | Miner Descent

Very interesting. Thanks

I send you the reward grant from 1484.

1484 August 10,Saturday Ralph Banastre obtained the promised reward ; he received Magazine, a grant of the Manor of Raiding (Yalden), in Kent, appears in the original charter of the Roses –

The King,

To all whom it may concern,

Greeting.

Whereas not only nobility of race but also equity of justice requires all men, and especially Kings and Princes, to remunerate with suitable rewards men who have served them well.

Know therefore that on account of the singular and faithful service our beloved liege and servant Ralph (Rauf) Banastre hath all along formerly rendered for us, not only by establishing our right and title, by the strength of which right and title we have lately come, the Lord helping us, to the throne of this our Kingdom of England, but also by suppressing the treasons and malice of rebels and traitors towards us, who had for some time since stirred up a traitorous commotion within this same realm of ours, and for the good and faithful service to us and to our heirs the Kings of England hereafter to be rendered by the same Ralph and his heirs for the defence of ourselves and of our kingdom aforesaid against all hostile traitors and rebels whatsoever, as often as there shall be need in time to come,

We, of our special grace, have given and granted, and by these presents do give and grant, to the aforesaid Ralph the Manor of Ealding, in our county of Kent, of the annual value of fifty pounds. To have and to hold the aforesaid Manor with the belongings and the outcome, profits, and returns from the same Manor, etc. for ever.

Witnessed by the King

at Westminster

the loth day of August, 1484

by brief of the Privy Seal

Note : The King also conferred upon ‘ his trusty and well beloved Squire, Thomas Mytton, the Sheriff of Shropshire, the Castle and Lordship of Cawes, with all the appurtenances thereto, amounting to the annual value of …, and late belonging unto our rebel and traitor Henry, late duc of Buckingham, in consideration of his good and acceptable service.

Cheers,

Debra Bannister Wetherbee