I just finished a War of 1812 story where two of our cousins were captured by the British and an uncle (their father and from the same company) was captured a year later and died in a Quebec City POW camp. (See my post Battle of Frenchman’s Creek Nov 28, 1812)

Today, I found another cousin who was captured by the British in the War of 1812.

Benjamin COLEMAN’s grandson Charles Colman (b. 8 Aug 1782 Newburyport, Essex, Mass – d. 12 Sep 1849 Brookfield, New Hampshire of consumption) enlisted as a sergeant in the 21st US Infantry Jan 2 1813 in Wakefield New Hampshire for 18 months under company commander Capt. Lemuel Bradford (b. 1 Dec 1775 -d. 14 Sept 1814 of wounds received during the War of 1812) Note: Sep 14 1814 was the day Francis Scott Key saw that “Our Flag Was Still There” at Fort McHenry.

According to his enlistment, Charles was 5′ 11 1/4″ or 6′ 0″ [Very tall for those days]. Blue eyes, Red Hair, Light Complexion; Yeoman or School Master; Newburyport or Boston.

Charles was in the roll of American prisoners of war arrived in schooner Lignan at Salem, Mar 16, 1815 captured at Sixtown Point, Henderson Bay on May 28, 1813. M.R. Captain James Green Jr’s. detachment Fort Pickering March 20, 1815. Present – Book 569; Discharged May 1, 1815

The Battle of Sacket’s Harbor, (Also called the 2nd Battle of Sacket’s Harbor) took place on May 29, 1813. A British force was transported across Lake Ontario and attempted to capture the town, which was the principal dockyard and base for the American naval squadron on the lake. They were repulsed by American regulars and militia.

The British force set out late on 27 May and arrived off Sacket’s Harbor early the next morning. The wind was very light, which made it difficult for Captain James Lucas Yeo (commander of the British naval force on the Great Lakes) to manoeuver close to the shore. He was also unfamiliar with the local conditions and depths of water. Shortly before midday on May 28, the troops began rowing ashore, but unknown sails were sighted in the distance. In case they might be Captain [later Commodore] Isaac Chauncey‘s fleet, the attack was called off, and the troops returned to the ships. The strange sails proved to belong to twelve bateaux carrying troops from the 9th and 21st U.S. Regiments of Infantry from Oswego to Sackets Harbor. The British sent out three large canoes full of Native American warriors and a gunboat carrying a detachment of the Glengarry Light Infantry to intercept them.

Charles Coleman’s 21st Regiment was being transported from Oswego to Sackets Harbor when it was intercepted by the British on May 27, 1813

The British force caught up with the convoy off Stoney Point on Henderson Bay. As the British opened fire, the Americans, who were mostly raw recruits, landed their bateaux (barges) at Stoney Point and fled into the woods. [Google Maps Directions from Stony Point to Sackets Harbor 13.5 Miles – 25 minutes] The Natives pursued them through the trees and hunted them down. After about half an hour, during which they lost 35 men killed, the surviving United States troops regained their vessels and raised a white flag. The senior officer rowed out to Yeo’s fleet and surrendered his remaining force of 115 officers and men including Charles Coleman. Only seven of the American troops escaped and reached Sackett’s Harbor.

Another account: On May 28, 1813, a flotilla of British warships appeared at the mouth of Black River Bay. The weather was miserable, however, with visibility poor and the lake calm. This prevented the British fleet from being able to tack into the harbor. So they waited. Through the fog they noticed barges loaded with reinforcements, elements of the 9th and 21st US Infantry from Oswego, headed for the harbor. The British dispatched their Indian allies to overtake the barges, who fearing for their lives pulled ashore at Stony Point. Pursued by Indians, many of the soldiers were hunted down and killed. Other boats that witnessed the carnage pulled directly for the British fleet, rather than take their chances on shore against the Indians. This skirmish is known as the Battle of Stony Point.

On May 28, 1813 Sir James Lucas Yeo, Commander of the Royal Navy on the Great Lakes, captured 115 American troops including Charles Coleman.

This delay nevertheless gave the Americans time to reinforce their defenses.

I found a book on archive.org published in 1879 by Charles Colman’s cousin’s wife Sarah Ann Smith (b. 1787 – d. 1879) titled Reminiscenses of a Nonagenarian.

This book has many interesting and amusing anecdotes about the Colman family which I”ll be sharing. Here’s what she has to add to the story of Charles Colman and the Battle of Sackett’s Harbor.

Charles was taken prisoner, held as a hostage, and confined in the jail at Quebec. With two others he escaped. Having stolen a calf, which they managed to dress and roast, they made the best of their way through the woods for several days, but were so blinded by mosquito bites they were unable to proceed, and were recaptured. Afterwards Mr. Colman was taken to Halifax. At the disbanding of the army he returned home, where he learned that at the time he was taken prisoner a Colonel’s commission was on the way to him, which he failed to get. But later he received the deed of one hundred and sixty acres of land, as other soldiers.

Back to the Battle of Sacket’s Harbor

The next morning, 29 May, Prevost resumed the attack. The British troops landed on Horse Island, south of the town, under fire from two 6-pounder field guns belonging to the militia and a naval 32-pounder firing at long range from Fort Tompkins. They also faced musket fire from the Albany Volunteers defending the island. Although the British lost several men in the boats, they succeeded in landing, and the Volunteers withdrew. Once the landing force was fully assembled, they charged across the flooded causeway linking the island to the shore. Although the British should have been an easy target at this point, the American militia fled, abandoning their guns. Brigadier General Brown eventually rallied about 100 of them.

The British swung to their left, hoping to take the town and dockyard from the landward side, but the American regulars with some field guns gave ground only slowly, and fell back behind their blockhouses and defenses from where they repulsed every British attempt to storm their fortifications.

Yeo had gone ashore to accompany the troops, and none of the larger British vessels were brought into a range at which they could support the attack. The small British gunboats, which could approach very close to the shore, were armed only with small, short-range carronades which were ineffective against the American defences.

Eventually one British ship, the Beresford, mounting 16 guns, worked close in using sweeps (long oars). When its crew opened fire they quickly drove the American artillerymen from Fort Tompkins. Some of the Beresford’s shot went over the fort and landed in and around the dockyard. Under the mistaken impression that the fort had surrendered, a young American naval officer, Acting Lieutenant John Drury, ordered the sloop of war General Pike which was under construction and large quantities of stores to be set on fire. Lieutenant Woolcott Chauncey had orders to defend the yard rather than the schooners, but had instead gone aboard one of the schooners, which were engaging the British vessels at long and ineffective range.

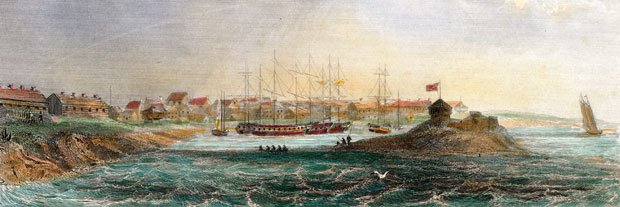

The “enemy” ship, Fair Jeanne, fires at Sackets Harbor — The 110 foot Canadian Brigantine Fair Jeanne travels the world. This Tall Ships training program has graduated over 2,000 young sailors.

By this time, Governor General of Canada, Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost was convinced that success was impossible to attain. His own field guns did not come into action and without them he was unable to batter breaches in the American defenses, while the militia which Brown had rallied were attacking his own right flank and rear. He gave the order to retreat. Prevost later wrote that the enemy had been beaten and that the retreat was carried out in perfect order, but other accounts by British soldiers stated that the re-embarkation took place in disorder and each unit acrimoniously blamed the others for the repulse.

The Americans for their part claimed that had Prevost not retreated hastily when he did, he would never have returned to Kingston. The U.S. 9th Infantry had been force-marching to the sounds of battle, but the British had departed before they could intervene.

The British defeat at Sacket’s Harbor compared badly with the victorious American opposed landings at York and Fort George, even though the odds at Sackett’s Harbor were slightly more favourable to the defenders. The chief reason was probably that the attack was launched without sufficient preparation, planning and rehearsal. The troops were an ad hoc collection of detachments, which had not been exercised together. This applied to the American regulars also, but since they were fighting from behind fixed defences, this mattered less.

Another account of the end of the battle and aftermath — The British commanders at the same time began to notice a rising plume of dust to the west of the village. They had learned from Americans captured at Stony Point that a column of Tuttle’s 9th Infantry had marched from Oswego the previous morning. Fearing these to be fresh reinforcements who would arrive on their rear, the British commander, Sir George Prevost, sounded a retreat. Tired and beaten, the British broke ranks and ran back to their landing boats, not even stopping to gather their wounded and dead. Once the landing party was safely back to the British fleet, they sent a representative under a flag of truce to ask that a landing party be allowed to tend to the casualties. The Americans refused.

In the aftermath of the battle, the fires in the Navy Yard were extinguished, but not before more than $500,000 worth of supplies and materials had been consumed. The new ship was saved with only minor damage. The wounded soldiers were taken to several homes in the village for care. One of these homes was the Sacket Mansion. The British were also tended to, while the dead were placed in an unmarked grave south of the village. The location of this grave has yet to be found. In all, the Americans lost 21 dead, 84 wounded and 26 missing. The British fared far worse for their effort: 48 dead, 195 wounded, and 16 missing.

So who won the battle? The British object was to destroy the Navy Yard and recapture supplies taken from York [today’s Toronto] and Gananoque. Thanks to some panicked Americans, they succeeded in destroying the Navy Yard and refusing the Americans use of their stores. Although the new ship was saved, the loss of rigging and sails in the fire delayed her commission for months and gave the British clear reign on Lake Ontario. The 250 or so Americans left at Fort Tompkins were beaten, and would not have held out long against an all-out British assault. The Americans, for their part however, inflicted disproportionately heavy damage on the British, something that Sir George Prevost would have to answer for in the coming months.

[Based out of Hamilton, Ontario, the 21st U.S. (Treat’s Company) seeks to recreate the life and times of a Soldier of the United States during the War of 1812]

They Built Things Better in the Past?

The ships the British and Americans were fighting to destroy and protect left something to be desired in the quality department. Here’s an historical note about their poor workmanship by Dr. Gary M. Gibson:

When something breaks shortly after you bought it, you might complain that “they built things better in the past.” However, if the past was Sackets Harbor during the War of 1812 and the items were warships, you would be well to prefer today’s models.

Between 1812 and 1815 the United States and Great Britain engaged in a war of ship carpenters. Although there were no major naval battles on Lake Ontario to compare with the actions on Lake Erie in 1813 and Lake Champlain in 1814, the shipbuilding efforts on Ontario far surpassed those on the other lakes. Workmen at the American shipyard at Sackets Harbor and the British shipyard at Kingston, Upper Canada, competed to be the first to build enough warships to gain and maintain control of Lake Ontario.

This competition led to hasty work. On the Atlantic, building a 44-gun frigate could easily take two or three years. At Sackets Harbor that feat was accomplished in two months. Even the first warship built at Sackets Harbor, the 24-gun [corvette]USS Madison, was ready to launch in only 45 days.

All this construction required skilled ship carpenters, and at Sackets Harbor there were never enough of them. The gap was filled by hiring common house carpenters. Unfortunately, you did not build a wooden warship like you did a barn. The shipwright at Sackets Harbor, Henry Eckford., had to compensate for this by altering the design to make the vessels easier (and faster) to build.

This nearly lead to disaster. In September 1814, the 22-gun brig USS Jefferson encountered a fierce gale on Lake Ontario and the vessel, rolling heavily and “twice on her beam ends” began to come apart. To save the ship, the captain, Charles G. Ridgeley, had to lighten the load on deck by throwing ten of her cannon overboard.

In January 1815 construction began on two huge warships, the 106-gun New Orleans and Chippewa.

[The first-rate ship-of-the-line, New Orleans was designed to carry a crew of 900 and was enclosed in a huge wooden ship house to protect it for future use, but in 1817, the Rush-Bagot Treaty between the United States and Great Britain limited all naval forces on the Great Lakes. The treaty provided for a large demilitarization of lakes along the international boundary, where many British naval arrangements and forts remained. The treaty stipulated that the United States and British North America could each maintain one military vessel (no more than 100 tons burden) as well as one cannon (no more than eighteen pounds) on Lake Ontario and Lake Champlain. The remaining Great Lakes permitted the United States and British North America to keep two military vessels “of like burden” on the waters armed with “like force”. The treaty, and the separate Treaty of 1818, laid the basis for a demilitarized boundary between the U.S. and British North America.]

[In 1816, a year after construction began] , with the war now over, a British foreman of shipwrights, John Aldersley, visited Sackets Harbor and inspected the incomplete New Orleans. He saw “the most abominable, neglectful, slovenly work ever performed …the timbers are in many instances thrown in one upon the other, without even the bark of the tree being taken off.” Aldersley noted that the New Orleans’ gun ports were created after the ship’s sides were completed, “the same as the doors and windows are cut out after a log house is framed.”

The incomplete USS New Orleans in 1883, the year she was sold for scrapping. She remained on the stocks, housed over, until sold on 24 September 1883 to H. Wilkinson, Jr., of Syracuse, New York.

Built quickly out of green wood, few of these warships survived for long. By the early 1820s most were reported to be “sunk and decayed.” The only exceptions were the incomplete New Orleans and Chippewa, which remained in good condition only because they had expensive shiphouses built over them. As a result, the New Orleans, slovenly construction notwithstanding, was still considered useful as late as the American Civil War, a half century later.

The Great Rope — One Last Fun Story

In May 1814, 84 men carried a ship’s cable weighing five tons from the mouth of Sandy Creek to Sackets Harbor, a distance of 20 miles. It took two days and they were left battered and bruised, but they did the job “can-do” American style.

The serpentine line of cable-carriers passed from village to village during the 20-mile journey where they were met with growing enthusiasm, refreshments, and replacements for those too exhausted or injured to continue. Mats of woven grass were fashioned to protect the shoulders of cable-carriers but all had large bruises. It was said that some carried the callous or mark on their shoulders the rest of their lives.

The Great Rope was the main anchor cable for the “Superior”, a frigate launched May 1, 1814 from Sackets Harbor under the command of Issac Chauncy. When armed, she was to carry 66 guns. The rope, under guard in Oswego, was 22 inches around and weighed 9,600 pounds. Although the rope traveled by boat most of the way, due to heavy fighting on Lake Ontario, the last leg of the trip was made over land on the backs of men. Here’s the complete story “.Events Surrounding The Battle of Big Sandy and the Carrying of the Great Rope in 1814 and the Ensuing 185 Years.” by Blaine Bettinger.

This reenactment rope is undersized. Plus the locals were the ones who pitched in and they wouldn’t have had hats with feathers. The original ships’ cable would have been four times as thick and heavy as the one depicted here.

Sources:

http://www.army.mil/article/85110/Sackets_Harbor_celebrates_War_of_1812___/

Pingback: Deacon Benjamin Coleman | Miner Descent

I found a book on archive.org published in 1879 by Benjamin Colman’s great-daughter-in-law Sarah Ann Smith (b. 1787 – d. 1879) titled Reminiscenses of a Nonagenarian .

This book has many interesting and amusing anecdotes about the Colman family which I”ll be sharing. Here’s what she has to add to the story of Charles Colman and the Battle of Sackett’s Harbor.

Charles was taken prisoner, held as a hostage, and confined in the jail at Quebec. With two others he escaped. Having stolen a calf, which they managed to dress and roast, they made the best of their way through the woods for several days, but were so blinded by mosquito bites they were unable to proceed, and were recaptured. Afterwards Mr. Colman was taken to Halifax. At the disbanding of the army he returned home, where he learned that at the time he was taken prisoner a Colonel’s commission was on the way to him, which he failed to get. But later he received the deed of one hundred and sixty acres of land, as other soldiers.

Pingback: Jacobus DeLange | Miner Descent