Stephen “Don Esteban” Minor (1760 – 1815) was just a second cousin of our Miner line, but his family story is too unique not to include. His children and grandchildren owned hundreds of slaves and some of the grandest plantations in Louisiana and Mississippi, yet most remained loyal to the Union.

- His son-in-law Willliam Butler Kenner received a franchise from the United States Congress to dig a large canal across New Orleans. The canal was never started, but Canal Street received its name from the aborted project.

- His grandson Minor Kenner founded Kenner, Louisiana, population 66,702 at the 2010 census.

- His son-in-law Henry Chatard was aide-de-camp to Major General Andrew Jackson and Assistant Adjutant General at the Battle of New Orleans

- His son-in-law James Campbell Wilkins was a Natchez, Mississippi, cotton planter, merchant, cotton factor, financier, and banker. As Captain of the Natchez Militia, he helped hold the endangered West side of the Mississippi during the Battle of New Orleans.

- His grandson Duncan Kenner (wiki), the richest of them all, tried to get England and France to recognize the Confederacy in exchange for emancipation.

- His son William John Minor was nationally recognized in the breeding and racing of horses. Under the pseudonym, “A Young Turfman,” Minor authored more than seventy articles on horse racing for the Spirit of the Times, a New York sporting-life newspaper aimed for an upper-class readership made up largely of sportsmen.William John acquired Hollywood Plantation (1,400 acres) and Southdown Plantation (6,000 acres) in Terrebonne Parish and Waterloo Plantation (1,900 acres) in Ascension Parish. His net worth, including hundreds of slaves, was estimated to be more than one million dollars in 1860.

Active in Whig politics in the years before the Civil War, William John Minor lobbied against secession throughout the South. When war did come, Minor remained loyal to the Union despite the social ostracism and economic losses that his family would suffer during and after the war.Today, Each fall, Southdown Plantation hosts the Voice of the Wetlands Festival showcasing dozens upon dozens of world class musical artists - William John’s daughter-in-law Kate Surget Minor was also a Unionist. She filed a petition with the Southern Claims Commission in 1871. The commission was to determine the validity of monetary claims of loyal southern Unionists whose property had been confiscated by the Union army during the Civil War. Kate’s claim for losses on Carthage and Palo Alto plantations totaled $64,155. However, after nearly a decade of litigation, and thousands of pages of testimony, the commission disallowed the majority of her claim and awarded only $13,072. Kate’s case is covered in detail in The Case of the Minors, A Unionist Family in the Confederacy by Frank Wysor Klingberg The Journal of Southern History Vol. 13, No. 1, Feb., 1947

Stephen Minor was born 8 Feb 1760 Greene County, Pennsylvania. His great grandparents were our ancestors William MINER and Francis BURCHAM. His grandparents were Stephen Minor and Athaliah Updyke. His parents were Capt. William Minor and Frances Ellen Phillips. (See William MINER‘s page for their stories)

Stephen first ventured to New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1779. He first married Martha Ellis 1790 in Louisiana. After Martha died, he married Katherine Lintot 4 Aug 1792 in Natchez, Adams, Mississippi. Stephen died 29 Nov 1815 in Natchez, Mississippi and is buried at Concord, the historic residence of the early Spanish governors at Natchez, Mississippi. For his story, see my post Stepehen Minor – Last Governor of Natchez

Children

Child of Stephen and Martha:

| Name | Born | Married | Departed | |

| 1. | Mary Minor | 4 Jul 1787 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi | William Kenner 19 Nov 1801 |

5 Oct 1814 Oakland Plantation, Louisiana |

.

Children of Stephen and Katherine:

| Name | Born | Married | Departed | |

| 2. | Martha Minor | ~1793 Natches, Adams, Mississippi |

Bef. 1795 Natches, Adams, Mississippi |

|

| 3. | Frances Minor | 27 Mar 1795 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi | Major Henry Chotard 27 May 1819 Adams, Mississippi |

10 May 1864 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi |

| 4. | Katherine Lintot Minor | 24 Jun 1799 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi | James Wilkins 11 Apr 1823 Adams, Mississippi |

5 Jan 1849 or 9 Jul 1844 Natchez, MS |

| 5. | Stephen Minor | ~1803 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi |

Charlotte Walker? | 29 Nov 1815 Natchez, MS or 26 Jun 1830 |

| 6. | William John Minor | 27 Jan 1808 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi | Rebecca Ann Gustine 7 Aug 1829 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, |

18 Sep 1869 Houma, Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana |

The wealthy in 19th Century Natchez: What did they contribute to economy? by Stanley Nelson “On the eve of the Civil War Natchez boasted one of the largest concentrations of men of great wealth of any town in the south. The notion of ‘wealthy Natchez’ was created largely by the presence of this plantation owners. The aristocrats’ contributions to the local economy, however, are debatable, for in many instances their principal holdings lay outside the town and country. Some paid almost all of their taxes to the Louisiana government (where their large plantations were located), few seem to have added much to the tax coffers of Natchez and Adams County.

A local newspaper, The Natchez Free-Trader, said the small farmer contributed much more to the local economy than the large plantation owner. In 1842, the paper reported:

“They (small farmers) would crowd our streets with fresh and healthy supplies of home productions, and the proceeds would be expended here among our merchants, grocers and artisans. The large planters –- the one-thousand-bale planters — do not contribute most to the prosperity of Natchez. They, for the most part, sell their cotton in Liverpool; buy their wines in London or Havre; their Negro clothing in Boston; their plantation implements and supplies in Cincinnati; and their groceries and fancy articles in New Orleans.

In 1854, Frederick Law Olmsted was a journalist working for the New York Times when he visited Natchez. In the days before he became famous for designing Central Park in New York, he strolled about the region and was overwhelmed by its beauty. Olmstead, however, was turned off by the attitude of the rich and described their “marble-like” behavior as they looked at others “stealthily from the corner of their eyes without turning their heads…” A man interviewed by Olmsted warned him of the “young swell-heads (rich)…Why, you can tell them by their walk…They sort o’ throw their legs as if they hadn’t got the strength enough to lift ’em and put them down in any particular place. They do want so bad to look as if they weren’t made of the same clay as the rest of God’s creation.”

1. Mary Minor

Mary Minor was the daughter of Martha Ellis and was said to have had a twin sister who died in infancy. Mary was married at such an early age to William Kenner that it has been theorized that Katherine might have wanted her step daughter out of the house. Mary had her first of 6 children at 14 and was dead by age 28. William was left with a very young family and did not remarry. It is thought that some of the children were sent to Natchez to be “taken in” for extended periods by family there. William was in the transporting business, had met Mary through his business with Stephen, and would have been able to get to Natchez on one of his boats to visit them.

Mary’s husband William Butler Kenner was born 4 Jul 1776 in Northumberland, Virginia. His parents were Rodham Kenner (1752 – 1819) and Sarah Carter (1754 – ) or Sarah Kennedy (1740 – 1820). William died 10 May 1824 in New Orleans, Louisiana.

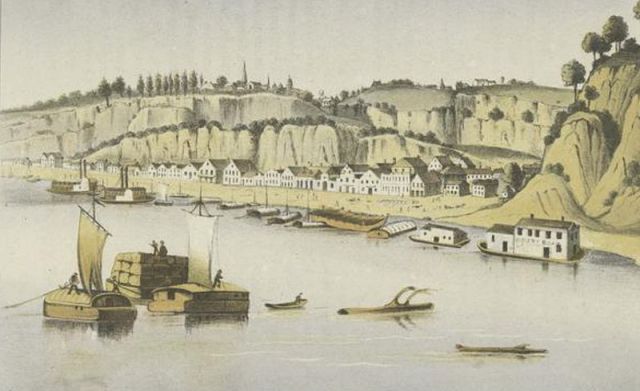

William was a New Orleans businessman, planter, and politician. He arrived at Cannes Brulees at the turn of the century. The population of New Orleans at that time was just a little over 8,000 people. But the city was on the verge of an economic boom. Kenner established a very successful mercantile and commission business.

In 1803 the Louisiana territory became part of the United States. William Kenner became a member of the legislative council and later helped organize a militia to repel the British in the Battle of New Orleans. The Governor of Louisiana, William C. C. Claiborne referred to Kenner as “An honest man, a respectable merchant, a man of sense and property.” According to Kenner’s descendants, the first steamboat to leave New Orleans carried a consignment from Kenner and Company.

Kenner played an important role in organizing a company which received a franchise from the United States Congress to dig a large canal across New Orleans. The canal was never started, but Canal Street received its name from the aborted project.

In 1810 Kenner purchased a sugar plantation in Ascension Parish. The growth of the sugar industry made this a very profitable investment, the income from which far exceeded Kenner’s mercantile business.

Kenner had married Mary Minor, the 14 year old daughter of a an officer with the Spanish troops stationed at Natchez. She gave birth to four sons and died at the age 27 in 1814, a year after giving birth to Duncan. William Kenner’s tragedies were made worse six years later when a trusted business partner absconded with most of his company’s assets. William Kenner died three years later at the age of 47.

Kenner Bio – Source: Old Families of Louisiana By Stanley C. Arthur, George Campbell Huchet de Kernion 1999

Children of Mary and William:

The Kenner brothers were orphaned at the ages of 10, 11, 13 and 15. A Creole lawyer and family friend, Etienne Masareau, salvaged enough of from the embezzlement disaster to provide each boy with an inheritance. These young men were destined to own all of Cannes Brulees.

William and Mary’s descendants lived on Oakland Plantation, Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, and on Roseland Plantation, St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, both sugar and rice plantations. The Jefferson Parish city of Kenner is sited on the family’s lands.

i. Patsy Kenner b. 1802 Louisiana; d. young

ii. Maria Kenner b. 18 May 1803 in Louisiana; d. 19 Oct 1806

iii. Martha Kenner b. 28 Sep 1804 Louisiana; d. 25 Apr 1873 Fayette, Fayette, Kentucky; m1. John Brown Humphreys (b. 1789 in Staunton, Virginia – d. 30 Jul 1835 in Lexington, Fayette, Kentucky) John’s parents were Alexander Humphreys (1757 -1802) and Mary Brown (1763 – 1836) John was nephew of James Brown, Louisiana’s third US Senator; m2. ~1838 to Robert Bruce; m3. Charles Oxley (b. 1805 Liverpool, England – d. 13 Apr 1854 Louisiana) Charles was a cotton broker. Martha left eight children.

Martha and Charles Oxley resided at Roseland Plantation in St. Charles Parish.

In the 1850 census, Charles and Martha were planters in St. Charles Louisiana with real estate valued at $90,000. They were living with four Humphreys children ages 16 to 24 and two Bruce children ages 10 and 12.

In the 1860 census, Martha’s real estate was valued at $250,000 and she was living with two adult daughters Fanny Humphreys (age 34) and Ella Humphreys (age 26)

iv. Frances Ann Kenner b. 20 Apr 1806 d. 12 Aug 1875 Christenburg, Virginia, leaving no descendants; m1. when she was quite young to John Dick ( – d. 1824); m2. 20 Jul 1826 to George Currie Duncan ( ~1799 Lancashire, England – 4 Mar 1870, Louisiana) George’s parents were William Macmurdo Duncan and Marianne [__?__]. George arrived in New York from Liverpool on the Hercules on 21 Nov 1822. He became a naturalized citizen 2 Mar 1855 in Louisiana.

G.C. Duncan to F. Anne Kinner, Marriage Contract. In City of New Orleans, LA, 19 July 1826, appeared George Currie Duncan Esquire aged 25 years, born in England, formerly of the City of Liverpool and now residing in this state where he has established his domicile, the legitimate son of William Macmurdo Duncan and Marianne Duncan, his father and mother both living in the City of Liverool; the said George Currie Duncan stipulating for himself and in his name, AND Mrs. Francis Anne Kenner aged 19 years, the minor widow of the late John Dick Esquire, emancipated by marriage, and the legitimate daughter of William Kenner and Mary Minor, her father and mother, both of MS, deceased, the said Mrs. widow Dick here stipulating for herself and in her name. Which said parties have settled the civil clauses and conditions of the marriage intended shortly to be had between them … (1) no community or partnership of acquits or gains between the parties who hereby expressly renounce the benefit of the law establishing in the State of LA said community or partnership … George Currie Duncan gives Francis Anne Kenner, widow of John Dick, the full administration and disposal of all her property. (2) Debts shall be paid by the party who contracted them. (3) Property of Francis Anne Kenner, widow of John Dick, consists of house, furniture, (etc.) and one undivided sixth part of one sixth of the whole estate of Stephen Minor her maternal grandfather deceased, one undivided sixth of the property of William Kenner and Mary Miner her deceased father and mother, her right as wife of the late John Dick deceased (money), and in one undivided sixth part of one fourth of a certain unsettled claim lately made by the heirs of the late Richard Ellis Senior, the deceased maternal ancestor of the said Widow Dick, of a large tract of land lying in the Attakapa. (4) Property of said George Currie Duncan is invested in commercial concerns, part of said property in State of England and elsewhere. (5) If they move, she retains the rights over her property. (6) She has no say in the property of George Currie Duncan. (7) and later. Mention of the laws of the State of LA. (FHL film 892,057)

11 Feb. 1829, George Currie Duncan and wife Frances Ann Duncan of City of New Orleans, LA, but now in the City of Natchez, to Nathaniel Dick and James Dick of said City of New Orleans and Christopher Todd and wife Sarah of State of TN; for $20,000 paid Frances A., sell the life estate of the said Frances Ann Duncan “(acquired by her the widow of the late John Dick deceased)” to one undivided moiety of all that plantation called Poplar Grove Plantation lying southerly of second creek in Adams Co. MS containing 11 arpens or French acres, being the same tract conveyed by Isaac Johnson to the late Benjamin Farrar decd. by deed 2 Dec. 1800 and conveyed by said Benjamin in his lifetime to said John Dick decd. by deed 29 Jan. 1820, together with the houses

Also the one undivided moiety of the following slaves, being upon the said Poplar Grove plantation, to wit, Joe, Class, Phil (right margin too faint) -dir, Billy, Anthony, Jack, Richard, Alick, Pier, Chester, B…, Cambridge, Less, Henry, Delozier, Supe?, Obadiah, Pane, Toby, Will, Isaac, Frank, Carolina, Adams, Old Jack, Little D..?, Jeffery, Dinah, Alley, Hetty, Bettie?, Vicy, Nancy, Judy, Candis Bets, Seyll?, Greser?, Sealy, Kathy, Affy, Harriet, Patience, Anna, Little R?? (too dark), Delphy, Eliza, Lotty, Ann, Sangar, Darkey, (MAD many more not copied).

Also the one undivided moiety of all the horses, mules, farming utensils, belonging to the said Poplar Grove Plantation, being the undivided moiety of … the life estate of the said Frances Ann Duncan as the widow of said John Dick deceased, and being secured in and to the said Frances Ann in her own right by a marriage contract entered into and executed by the said parties of the first part in the city of New Orleans on 19 July 1826, recorded in Book P, pg.492, 493 of the records of deeds of Adams Co.; also all the estate, etc., of said George Currie Duncan and Francis Ann Duncan or either of them in the same. /s/ Frances Ann Duncan, G. Currie Duncan. Ack. 11 Feb. 1829, no wit.

1 Feb. 1829, Nathaniel Dick and James Dick and Christopher Todd & wife Sarah by their attorney said Nathaniel Dick, to Mrs. Frances Ann Duncan of City of New Orleans, mortgage the life estate during the lifetime of said ?? to one undivided moiety of the plantation called Poplar Grove Plantation, slaves, etc., they to pay $23,000. /s/ Nathl. Dick, James Dick, Christopher Todd, Sarah Todd. Ack. 11 Feb. 1829.

v. Stephen Minor Kenner b. 18 Feb 1808 Louisiana; d. 10 Feb 1862; m. Eliza Davis (b. 1811 in Louisiana – d. 1862 in Louisiana) Minor and Eliza had three children born between 1830 and 1841.

Down river from Oakland was Belle Grove Plantation, located about where the Louis Armstrong Intl Airport is today. Minor Kennedy acquired this property from through his wife, Eliza, who was heir to the property through her widowed mother Maria Holliday.

The Kenners acquired Pasture Plantation in parcels. By 1845 the Pasture Plantation property was owned entirely by Minor Kenner.

Around 1853 Railroad Fever struck the Delta region. A coalition of New Orleans business owners had put up 3 million dollars toward a railroad that would run to Jackson, Mississippi. They purchased some of the Kenner’s property and began laying 55 miles of trackbed from Manchac to Osyka.

Minor Kenner was possessed by the idea that Cannes Brulees could become a city. First, there was the proximity to New Orleans. Second, was the presence of the railroad. He hired a surveyor, W.T. Thompason to lay out a plan for the development of Oakland and Belle Grove. The plan was completed on Mar 2 1855, a date generally considered the city’s birthday. Kenner and Thompson’s vision would take time to develop, but today the basic layout of Old Kenner is very similar to the plan layed out in 1855.

The city of Kenner near New Orleans is on land that consisted of three plantation properties that had been purchased by the Kenner family. At the time, all land north of what is now Airline Highway was swampland.

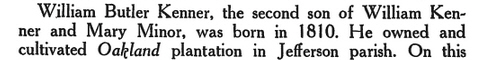

vi. William Butler Kenner b. 11 Mar 1810 in Virginia; d. 24 Sep 1853; m. 12 Sep 1832 in Cincinnati, Ohio to Rumahah A. Riske (b. 1811 in Ludlow Station, Ohio – d. 24 Feb 1885) Rumahah’s parents were David Riske ( – 1818) and Charlotte Chambers (1768 – 1821) William and Rumahah had seven children born between 1833 and 1846.

The area now called Kenner consisted of three large plantation properties known by the names Oakland, Belle Grove and Pasture. Farthest upriver, bordering St. Charles Parish, was the Oakland tract, owned by Louis Trudeau. After a decade of persistent effort the Kenner brothers acquired the entire Trudeau property. The Oakland Plantation was acquired by William Butler Kenner in 1841.

Despite New Orleans economic and cultural success, it was not a healthy city to live in. Much of the sewer system was open and provided a breeding ground for mosquitoes. Yellow fever outbreaks were common. Flooding was frequent and the threat of hurricanes hung over the city for six months out of the year. On May 3, 1849 a 100 foot breach in the levee near Little Farms in Jefferson Parish sent flood waters six feet deep surging from the Mississippi toward the lake. Metairie Ridge deflected the water and steered it into New Orleans. Streets became rivers and 12,000 people were left homeless.

As a cultural and economic hub New Orleans had earned the nickname “Queen City of the South.” Living conditions in the city had earned it another nickname: “The Watery Grave.” Many residents of New Orleans were making an effort to spend as much time away from the “Queen City” as possible. The north shore of Lake Ponchartrain, the Gulf Coast and the northern parts of the state provided temporary escape. But these areas were too far from the city’s commercial operations to provided a permanent residence. Cannes Brulees was not.

By this time tragedy had again visited the Kenner family. William Butler Kenner had become involved in a failed business venture which left him in such debt that he had to heavily mortage the Oakland Plantation. In 1853 a Yellow Fever epidemic struck New Orleans and the surrounding area. 11,000 died, including William Butler and his 12 year old son. Minor Kenner became the executor of William Butler’s estate.

Their children included Philip Minor Kenner (1833-circa 1890), Josephine, Charlotte “Lottie” K. Harding, Butler, Mary Minor, Sarah Belle, and Fredrick Butler Kenner. Philip Kenner served as a lieutenant during the Civil War; he married Ella Humphreys.

vii. George Rappele Kenner b. 1812; d. 25 Sep 1852 in Craney, Texas; m. 11 Mar 1840 to Charlotte Chambers or Charlotte Jones

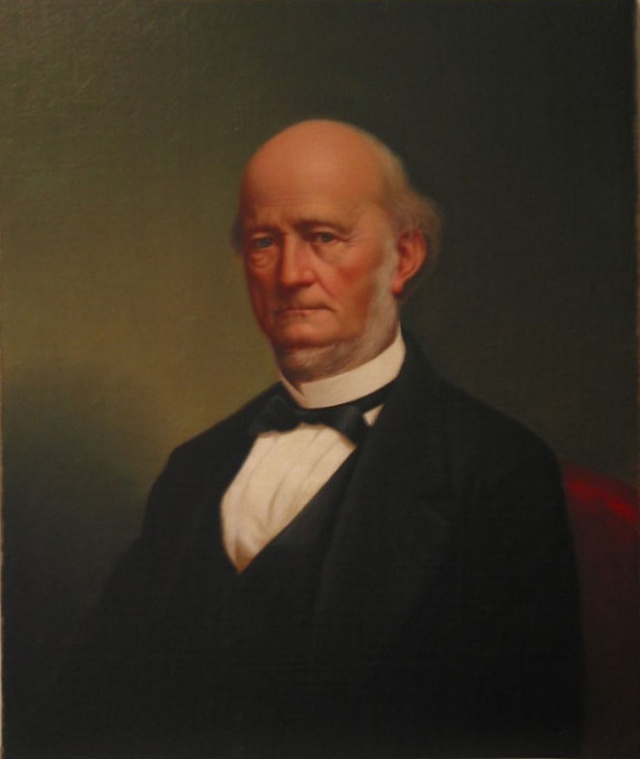

viii. Duncan Farrar Kenner (wiki) b. 1 Feb 1813 in Bienville St, New Orleans, Louisiana; d. 3 Jul 1887 Carondelet St, New Orleans; m. Jun 1839 to Anne Guillelmine Bringier (b. 1815; bapt 24 Aug 1823 in Hermitage, Ascencion Parish, Louisiana – d. 6 Nov 1911 in New Orleans, Louisiana) Anne’s parents were Michel Douradou Bringier (1789 – 1847) and Elizabeth Aglae Du Bourg (1798 – ) a prominent French Creole family. Duncan and Anne had two children.

In the 1850 census, when Duncan’was 35 his real estate was valued at $300,000. In the 1860 census, real estate was $190,000 and personal property (slaves) was $250,000.

As a wedding present, Duncan commissioned construction of the great house at Ashland. Construction began in 1840, and the project was completed by 1842. The Greek Revival great house at Ashland is considered an architectural masterpiece. The quarters and the sugarhouse were built at about the same time the great house was erected. It is likely that the great house, the sugarhouse, and the quarters were all built by the plantation’s slaves.

Ashland is representative of the massiveness, simplicity, and dignity which are generally held to epitomize the Classical Revival style of architecture. Free of service attachments and with a loggia on all four facades, it is a more complete classical statement than the vast majority of Louisiana plantation houses. With its broad spread of eight giant pillars across each facade and its heavy entablature, Ashland is among the grandest and largest plantation houses ever built in the state.

The walls of Ashland (as the Kenner plantation was then known) were adorned with paintings of horses, and the grounds included a racetrack.

Duncan Kenner bought his brother’s interest in the plantation in 1844. He named his property “Ashland” after U.S. statesman Henry Clay’s plantation in Kentucky. Kenner eventually expanded his land holdings to over 2,200 acres. His estate included the neighboring Bowden Plantation, complete with its own sugarhouse, which he bought in 1858.

After Duncan’s death, Kenner’s estate was sold in March 1889 to George B. Reuss, an Ascension Parish planter. The Reuss family moved into the Ashland great house. Reuss renamed the plantation “Belle Helene” in honor of his recently born daughter, Helene. Belle Helene remained a major sugar plantation into the second decade of the twentieth century. The cabins continued to be used by the plantation workers.

Helene Reuss moved from the Ashland-Belle Helene great house soon after her marriage in 1908. However, other members of the Reuss family lived there until sometime in the 1920s. The house had deteriorated significantly by the time a restoration effort began in 1946. Although it subsequently fell victim to further decay and haphazard renovation, the house is being stabilized by its present owners, Shell Chemical Company.

As was the case with almost all the other great Louisiana plantations, Ashland passed into anonymity along the banks of the Mississippi. The quarters fell silent, the sugarhouse collapsed, and the land was divided and sold. Much of the former Ashland-Belle Helene Plantation tract currently serves as the site for major chemical production facilities owned by Shell Chemical Company and the Vulcan Materials Corporation.

Duncan Farrar Kenner (1813 – 1887) Artist Unknown — Done from life. ca. 1884-1887 – Could have been painted in New York or New Orleans

Duncan Kenner was a CSA diplomat, legislator, and millionaire planter.

Although a large slave owner, [the US census reported that Kenner had 117 slaves in 1840 and 169 slaves in 1850.] early in the war he had become convinced that the emancipation of slaves was the only way to gain independence for the Confederacy. Kenner first broached the idea to Davis and the cabinet in early 1863.

In 1865, he was sent by Jefferson Davis as special commissioner and minister plenipotenitaryto Englandand France to secure the recognition of the Confederate States of America. Davis, through Kenner, offered the emancipationof the Confederate slaves in exchange for recognition of the Confederacy by Britain and France. But it was too late, the European powers knew that Confederate resources were rapidly dwindling and defeat was near. Kenner believed [Papers of Jefferson Davis]: “Had I gone to Europe in 1863 instead of 1865 I have no doubt that I would have been successful … Slavery was the bone of contention.” He also believed that he might have been successful in securing the $15 million loan. “It is nearer to being accomplished than the political mission.”

Duncan Kenner’s European Diplomacy Source: Confederate Goliath: The Battle of Fort Fisher By Rod Gragg, Edward G. LongacreFort Fisher kept North Carolina’s port of Wilmington open to blockade-runners supplying necessary goods to Confederate armies inland. By 1865, the supply line through Wilmington was the last remaining supply route open to Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. When Ft. Fisher fell after a massive Federal amphibious assault on Jan 15, 1865, its defeat helped seal the fate of the Confederacy

Here’s another account of Kenner’s European adventurein Retrospectaions of an Active Life, published in 1909, authored by John Bigelow, former Union envoy in Paris:

“Kenner was a member of the Confederate Congress. He had long been satisfied that it was impossible to prosecute the war to a successful issue without a recognition of the Confederacy by at least one of the maritime powers of western Europe, into the ports of which the Southern States might carry their prizes, make repairs, and get supplies. He was also satisfied that they would never secure recognition or any substantial aid so long as the foundations of their projected new empire rested on slavery. He communicated these views to President Davis. The President asked what he had to propose in the premises. He said he wanted the President to authorize a special envoy to offer to the governments of England and France to put an end to slavery in the Confederacy if they would recognize the South as a sovereign power. The President consented to submit the suggestion to several of the leading members of the Congress, by some of whom it was roughly handled.

They protested that the emancipation of the slaves would ruin them, etc. Mr. Kenner told them that he and his family owned more slaves, probably, than all the other members of the Congress put together, and that he was asking no one to make sacrifices which he was not ready to make himself. The result of the consultations was that Kenner himself was sent abroad by President Davis, either with or without the confirmation of the Senate, with full powers to negotiate for recognition on the basis of emancipation. As soon as he received his commission he took a special train to Wilmington, North Carolina. On his arrival there he found either that the blockade was too strict, or that there was no suitable transportation available from that port, and returned at once to Richmond, determined to go by the way of the Potomac and New York. When he mentioned his purpose to Davis, “Why, :Kenner,” he exclaimed, “there is not a gambler in the country who won’t know you. You will certainly be captured.” Kenner had been one of the leading turfmen in the South for a generation. “I am not afraid of that,” said Kenner. “There is not a gambler who knows me who would betray me. I am going to New York.”

Being a very bald man, Kenner provided himself with a brown wig as his chief if not only disguise, and proceeded on his journey. By hook and by crook he finally reached New York and drove to the Metropolitan Hotel. Discovering that the waiters were colored, and that there were too many chances of some of them knowing him, also that ex-Senator Foote of Mississippi, who had deserted the Confederates, was residing at this hotel, he succeeded in getting a note to Mr. Hildreth, then managing the New York Hotel, and an old and trusty friend, asking that a certain room on the lower floor and north side of the hotel be made ready for him, and named the hour that he might be expected, adding that he could not sign the letter, but was a friend. At the time named he went to the hotel and directly to the room he had ordered. The fireman was preparing a fire. While at his work at the grate the door opened, and in walked Hildreth to see who his ‘friend,’ and new lodger might be. Upon recognizing Kenner, he exclaimed, “Good God!” He was checked from continuing by observing Kenner’s fingers on his lips.

They talked upon indifferent matters until the fireman left, and then Hildreth asked Kenner, what could have brought him to New York at such a time. “Do you know,” said he, “that it is as much as your life is worth to be found here?”

“I am going to sail in the English steamer on Saturday, ” said Kenner, and I wish to stay quietly with you until then. You can denounce me to the government if you choose, but I know you won’t.”

Kenner did not leave his room till he left it in a cab for the steamer. His meals were served in his room by Hildreth’s personal attendant. As soon as Kenner arrived in London he sought an interview with Palmerston, to whom he unfolded his mission. Palmerston said that his proposition could not be entertained without the concurrence of the Emperor of France.

“With the Emperor’s concurrence would you give us recognition?” asked Kenner.

“That,” replied Palmerston, “would be a subject for consideration when the case presents itself, and may depend upon circumstances which cannot be foreseen.” Kenner went to Paris and had an interview with the Emperor, who told him he would do whatever England was willing to do in the premises, and would do nothing without her.

Kenner then returned to Palmerston to report the Emperor’s answer. During his absence, the news of Sherman’s successful march through the South had reached London.

Palmerston’s answer to him was, “It is too late.”

Duncan was a CSA Congressman. Served in many posts including, Member of Lousiana State House of Representatives in 1836, Member of Louisiana State Senate, Delegate to Louisiana State Constitutional Convention (1844, 1852), Delegate from Louisiana to the Confederate Provisional Congress (1861-1862), Representative from Louisiana in the Confederate Congress (1862-1865) and Candidate for United States Senator from Louisiana in 1878

Duncan, the youngest brother, eventually took over William’s sugar plantation in Ascension. On this property he built a splendid mansion surrounded on all four sides by a magnificent white colonnade. The building was designed by James Gallier, the most famous Southern architect of the day. Duncan named it Ashland after the home of Henry Clay.

Kenner became a wealthy sugar planter. He used scientific techniques and was said to be the first man in Louisiana to use a railroad to bring sugar cane from the fields to the mill.

By 1845 New Orleans had a population of about 110,000, making it the nation’s fourth largest city. New Orleans had become a major economic hub with dozens of steamboats departing daily carrying sugar, cotton, grain and other goods. Norbert Rillieux had perfected the “multiple effect” process for refining sugar, revolutionizing the industry and providing for significant financial rewards to those who held lands able to grow the cane. Duncan Kenner prospered, listing sales of 1.5 million pounds of sugar in 1850.

Duncan of Ashland Plantation and his Uncle William John Minor each had a private track for training purposes and took many honors on the turf, racing their fine horses at Baton Rouge, New Orleans, Natchez, and Mobile.

Kenner served for several terms in the Louisiana House of Representatives and was a member of the state constitutional conventions of 1845 and 1852, having presided over the latter conclave.

Kenner was a member of the Confederate Congress and chairman of its Ways and Means Committee. In 1862, he proposed a national income tax of 20%, including a schedule of exemptions. His tax bill went nowhere, but in April 1863, Congress passed another act calling for a tax “in kind”, payable with goods and agricultural produce rather than money, and based not on property but on agricultural produce and income it generated.

In July 1863, while visiting his family at his Ashland Plantation during a recess in the legislature, Kenner narrowly avoided capture by the Union army, making his escape after being warned by one of his slaves of the advance of Federal troops.

Much of Kenner’s property was confiscated and his slaves were freed, All of Kenner’s prized racehorses, one of the largest stock farms in the United Statesmost of his wine and liquor, and the Kenner family silver were captured by the Federal troops..

By this time he had become convinced that the emancipation of slaves was the only way to gain independence for the Confederacy.

In 1865, he convinced Jefferson Davis to send him as special commissioner to England and France to secure the recognition of the Confederate States of America. Davis, through Kenner, offered the emancipation of the Confederate slaves in exchange for recognition of the Confederacy by Britain and France.

Even though Ashland had been captured by the Union army, sugar was still produced by the estate. The sugarhouse and its machinery were left undamaged. The overseer maintained control of the plantation and its labor force throughout the war. During the last two years of the war, Ashland was rented, and then confiscated by the Freedmen’s Bureau, a Federal agency formed to assist the freed slaves. In 1866, Kenner returned from Europe, swore an oath of allegiance to the Union and was repatriated, thereby recovering the ownership of Ashland.

Not long after the Civil War, Duncan Kenner moved to New Orleans to pursue his law practice. The workers on Ashland Plantation, probably including Kenner’s freed slaves, continued to live in the antebellum quarters. Continued residence in the quarters is partly explained by the nature of labor on sugar plantations in the post-Civil War period. Following Emancipation, working for wages replaced slavery on sugar plantations. As was the custom on sugar plantations before the Civil War, sugar laborers were organized into groups of workers who performed specific jobs directed by an overseer. On many plantations, the antebellum quarters were used to house these workers. The laborers were paid either in cash or in credits for use at the plantation store. A store was probably established soon after the war.

At his death Duncan Kenner was again a millionaire.

3. Frances Minor

Frances’ husband Major Henry Chotard was born 3 Mar 1787 in Santo Domingo. His parents were Jean Marie Joseph Chotard ( – 1810) and Henrietta Lofont. Henry died 7 Jul 1870 in Natchez, Adams, Mississippi.

During the War of 1812, Major Henry E. Chotard was aide-de-camp to Major General Andrew Jackson and Assistant Adjutant General New Orleans. An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer. LSU archives contain 1810-1818 Papers pertaining to Chotard’s service include recruiting reports, a letter from an officer at Mobile regarding reinforcements, prospects for victory, and Indian involvement.

The Battle of New Orleans on Jan 8 1815 was the final major battle of the War of 1812. American forces defeated an invading British Army intent on seizing New Orleans and the vast territory the United States had acquired with the Louisiana Purchase. The Treaty of Ghent, having been signed on Dec 24, 1814, was ratified by the Prince Regent on Dec 30, 1814 and the United States Senate on Feb 16, 1815. Hostilities continued until late February when official dispatches announcing the peace reached the combatants in Louisiana, finally putting an end to the war. The Battle of New Orleans is widely regarded as the greatest American land victory of the war and for many years January 8 was celebrated as a holiday on equal footing with the 4th of July.

In his report of the battle of December 23 Jackson wrote: “Colonels Butler and Piatt and Major Chotard, by their intrepidity, saved the artillery.”

On the morning of December 23, British General John Keane and a vanguard of 1,800 British soldiers reached the east bank of the Mississippi River, 9 miles south of New Orleans. Keane could have attacked the city by advancing for a few hours up the river road, which was undefended all the way to New Orleans, but he made the fateful decision to encamp at Lacoste’s Plantation and wait for the arrival of reinforcements.

During the afternoon of December 23, after he had learned of the position of the British encampment, Andrew Jackson reportedly said, “By the Eternal they shall not sleep on our soil..” That evening, attacking from the north, Jackson led 2,131 men in a brief three-pronged assault on the unsuspecting British troops, who were resting in their camp. Then Jackson pulled his forces back to the Rodriguez Canal, about 4 miles south of the city. The Americans suffered 24 killed, 115 wounded, and 74 missing, while the British reported their losses as 46 killed, 167 wounded, and 64 missing.

Historian Robert Quimby says, “the British certainly did win a tactical victory, which enabled them to maintain their position”. However, Quimby goes on to say, “It is not too much to say that it was the battle of December 23 that saved New Orleans. The British were disabused of their expectation of an easy conquest. The unexpected and severe attack made Keane even more cautious…he made no effort to advance on the twenty-fourth or twenty-fifth”. As a consequence, the Americans were given time to begin the transformation of the canal into a heavily fortified earthwork.

Major Henry Chotard, a gallant Mississippian of the Third U.S. Infantry, Adjutant-General on the staff of General Jackson, was wounded by a shell in the British bombardment of the Chalmette plantation buildings January 8 1815. (Latour.)

In the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, Jackson’s 5,000 soldiers won a decisive victory over 7,500 British. At the end of the battle, the British had 2,037 casualties: 291 dead (including three senior generals), 1,262 wounded, and 484 captured or missing. The Americans had 71 casualties: 13 dead, 39 wounded, and 19 missing.

Chotard’s Jan 17 1815 letter conveys Jackson’s very detailed orders for Brigadier General David Bannister Morgan to march 600 men down river, cross behind the retreating British troops, and make preparations to attack them.

Given that the units involved were veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, it’s unlikely the British ran through the briars and ran through the brambles

And ran through the bushes where a rabbit couldn’t go.

And ran so fast that the hounds couldn’t catch ’em

Down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico.

Henry, Frances and their four young children returned to New Orleans from Sicily via Le Havre on the Mary Howland arriving on 30 Dec 1826

The Chotard family lived at Somerset Plantation in south Louisiana. According to Reader’s Digest, “Henry Chotard of Natchez, for example, built stables for his horses with hand-carved mahogany stalls and marble troughs, and commissioned a silver nameplate for each horse.”

In the 1850 census, Henry and Frances were planters in Adams, Mississippi with real estate valued at $30,000. The 1850 slave schedule shows they had 100 slaves.

Children of Frances and Henry:

i. Catherine Chotard b. 2 Jan 1820 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi; d. 12 Feb 1877 New Orleans; Burial: Natchez City Cemetery; m. Horatio Sprague Eustis (b. 25 De 1811 Newport, Newport, Rhode Island – d. 4 Sep 1858 Issaquena County, Mississippi) Horatio’s parents were Gen. Abraham Eustis (wiki) (1786 – 1843) and Rebecca Sprague. Eustis, Florida and Fort Eustis Virginia each named in Abraham’s honor. Catherine and Horatio had twelve children between 1840 and 1860.

Horatio (Harvard 1830) was fitted for college at Round Hill School, Northampton, Mass., under the superintendence of Joseph Green Cogswell (H.C. 1806) and George Bancorft (H.C. 1817). After leaving college, he studied law; went to the West; and finally settled, as a lawyer, in Natchez, where he continued in the practice of his profession, with the exception of an interval of a year of two, until his death.

All four of Horatio’s sons were sponsored at Harvard by their uncle Henry Lawrence Eustis (wiki) (1819 – 1885) who organized the engineering department when it opened in 1849 and was appointed first professor of engineering. Two of the brothers served in the CSA and were killed in action.

Two of Horatio’s sons Horatio Jr. and Richard were killed in action fighting for the CSA. Lt. Horatio Eustis (Harvard 1861) died after his leg was blown off Sep 19 1864 at the Third Battle of Winchester, Virginia

Horatio’s brother Henry graduated from Harvard University in 1838 and then attended West Point. After graduating first in his class, Eustis was assigned to engineering roles, including working on several improvements to the unfinished Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. Eustis taught engineering at West Point from 1847 to 1849. He resigned on November 30, 1849, and took an appointment teaching engineering at Harvard. Henry served as a general in the Union Army during the Civil War, later returning to Harvard becoming the dean of the Lawrence Scientific School, later the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

ii. Henry Chotard. b. ~1820 Mississippi

iii. Amenaide Chotard b. 5 Feb 1822; d. 16 Feb 1895; m. 29 Mar 1843 to Edward Kemp Chaplain (b. 12 Nov 1814 – d. 14 Oct 1853. Amenaide and Edward had five children born between 1844 and 1851.

iv. Frances “Fanny” Chotard b. ~1823 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi; d. 1892

In the 1870 census, Fanny (age 45) and Maria (age 33) Chotard were farming in Natchez. Their real estate was valued at $25,000 and their personal estate at $1,450 each.

v. John Charles Chotard b. ~1823 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi; m. 28 Jun 1859 Natchez to Mary A. Barnard.

In 1850 J C Chotard of Natchez was a freshman at Yale University living at 4 St. John’s Place. In 1852 he was studying applied chemistry and living in Analyt. Lab. J. C. Chotard was a private in Capt. Bauck’s Company, Mississippi Cavalry. John Charles Chotard Solider of CSA was buried in 1863 in Bethsalem Cemetery, Boligee

Greene, Alabamavi. Richard D Chotard b. Oct 1825 in Adams, Mississippi; d. Sep 1887 in Natchez, Adams, Mississippi; m. ~1846 to Elizabeth J. Bernard (b. 2 Nov 1830 – d. 9 Jun 1905) Richard and Elizabeth had six children born between 1847 and 1866.

vii. Henry Chotard b. 29 Nov 1827 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi; d. Jan 1895 in Mississippi

In the 1860 census, H Chotard and his wife S. M. [__?__] (b. ~1830 Mississippi) were farming in Wards 4 and 5, Concordia, Louisiana. His real estate was valued at $245,000 and personal estate at $3000

viii. Henrietta Chotard b. 5 Dec 1829 Natchez, Adams, Mississippi; d. 10 Oct 1910

In the 1880 census, Henrietta Chotard (44) was living with her sisters Mariah Chotard (35), Amenaid Chaplain (38) and Fannie Chotard (34) and her nephew Henry Chotard (18)

and niece Mary E. Chaplain (27) in Court House, Adams, Mississippiix. William Minor Chotard b. 27 Jan 1835; d. 25 May 1836.

x. Mariah “Maria” Marshall Chotard b. 27 Nov 1837 in Natchez, Adams, Mississippi; d. 6 Dec 1912 in Natchez, Adams, Mississippi; m. 10 Dec 1889 Somerset Plantation, Adams, Mississippi to Farrar B. Conner (b. 19 Feb 1834 in Clifford Plantation, Natchez – d. 25 Mar 1904 at Somerset Plantation, Natchez) Farrar’s parents were William C. Conner (1798 – 1843) and Jane Elizabeth Boyd Gustine Conner (1803 – 1896) Farrar had first married Mary Elizabeth Louise McMurran (1835 – 1864) and had three children. He owned and/or managed Rifle Point plantation near Waco in McClennan County, Texas.

Maria (age 50) and Farrar (age 55) married late in life

In Jun 1861 Farrar joined Adams Troop cavalry company under William T. Martin, CSA

LSU Archives include a series of letters (1866-1867) to Lemuel, Sr., from his brother Farar B. Conner, concerning the management of his plantation Rifle Point, in Waco, Texas, in the postbellum days, and describing labor shortages, relations with freedmen and the Freedmen’s Bureau, cotton production and sales, problems with boll weevil infestations, and financial difficulties.

In the 1870 census, Fanny (age 45) and Maria (age 33) Chotard were farming in Natchez. Their real estate was valued at $25,000 and their personal estate at $1,450 each.

4. Katherine Lintot Minor

Katherine’s husband Capt. James Campbell Wilkins was born 27 Oct 1786 in Carlisle, Cumberland, Pennsylvania. His parents were John Wilkins Jr . (wiki) (1761 – 1816)and Catherine Stevenson. His grandparents were John Wilkins and Catherine Rowan. James first married about 1810 to Charlotte Frances Bingaman (b. 10 May 1794 Kentucky – d. 10 Oct 1820 in Bay of St Louis), and had three daughters including Charlotte Catharine Wilkins who married Samuel Stillman Boyd. James died 9 Apr 1849 in Louisville, Jefferson, Kentucky.

Katherine’s father-in-law John Wilkins Jr. (1761 -1816) served as Quartermaster General of the United States Army from 1796 to 1802.

John Wilkins Jr. was a U.S. Major General who served as Quartermaster General of the United States Army from 1796 to 1802. At age 15 Wilkins enlisted for the Revolution, and was assigned as Surgeon’s Mate of the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment. As a result of this service Wilkins earned the nickname “Doctor”. After the war Wilkins became a merchant and contractor in Pennsylvania and Presque Isle, Michigan, providing supplies and equipment to the United States Army in the Northwest Territory. In 1793 Governor Thomas Mifflin appointed Wilkins as Brigadier General of the Allegheny County Militia as part of Pennsylvania’s response to the Whiskey Rebellion.

President George Washington appointed Wilkins as Quartermaster General of the United States Army in June, 1796. In October Wilkins attempted to resign, pleading the necessity of personal business. His resignation was not accepted and he continued to serve, overseeing the supplying and equipping of an expanded Army in anticipation of war with France. The dispute with France was resolved without fighting, and Wilkins served until his position was abolished in March, 1802 as part of a downsizing of the Army. After leaving the Army, Wilkins returned to his business interests in Pennsylvania, including serving as President of the Pittsburgh branch of the Bank of Pennsylvania

James Campbell Wilkins

James was a Natchez, Mississippi, cotton planter, merchant, cotton factor, financier, and banker. Born in Pennsylvania in 1786, he came to Adams County around 1805. He participated in the Battle of New Orleans, the last general assembly of the Mississippi Territory, and the constitutional convention for the new state. Between 1828 and 1835 he attempted an unsuccessful political career. He was associated prominently with four banks at Natchez (1824-1840), but lost most of his fortune in 1841 and died at Lexington, Kentucky, in 1849.

The James Campbell Wilkins Papers (1801-1852) are stored at the University of Texas. The papers include correspondence, financial records, and legal documents relate to the lives and careers of Wilkins, his family, and business associates and concern the cotton trade; business of commission merchants in Natchez, Mississippi, and New Orleans, Louisiana; plantation life and economy; slavery; and the planter elite of the Natchez and Adams County area.

Included is material concerning James Campbell Wilkins’s uncle, Charles Wilkins, Lexington, Kentucky, merchant and provisioner of the U. S. Army’s work on the Natchez Trace road (1801-1807); James Campbell Wilkins’s work as a commission merchant in Natchez; his partnership (1816-1834) with John Linton in New Orleans; his business as a planter; activities of individuals and families, including George Adams, Adam Lewis Bingaman, Stephen Duncan, Levin R. Marshall, and the Minor family; and the 1836 sale and transportation to the South of a group of 50 slaves.

Capt. James Campbell Wilkins and the Battle of New Orleans

At the Battle of New Orleans, General Edward Pakenham ordered a two-pronged assault against Jackson’s position. Colonel William Thornton (of the 85th Regiment) was to cross the Mississippi during the night with his 780-strong brigade, move rapidly upriver and storm the batteries commanded by Commodore Daniel Patterson on the flank of the main American entrenchments and then open an enfilading fire on Jackson’s line with howitzers and rockets. Then, the main attack, directly against the earthworks manned by the vast majority of American troops

The only British success at was on the west bank of the Mississippi River, where William Thornton‘s brigade, comprising the 85th Regiment and detachments from the Royal Navy and Royal Marines, attacked and overwhelmed the American line. General Lambert ordered his Chief of Artillery, Colonel Alexander Dickson, to assess the position. Dickson reported back that no fewer than 2,000 men would be needed to hold the position. General Lambert issued orders to withdraw after the defeat of their main army on the east bank and retreated, taking a few American prisoners and cannon with them.

The Natchez Volunteer Riflemen, under Captain James C. Wilkins, “by the most strenuous efforts reached New Orleans on Jan 8 1815, at an early hour in the morning. They were hurrying to the battlefield when they perceived the American forces on the opposite bank of the river in great confusion retreating before a British regiment. Having received no orders it occurred to Captain Wilkins that the best service he could render would be to cross over and reinforce our defeated party. A couple of plantation ferry boats enabled him to cross, and he immediately took a strong position behind a ditch and sent Lieutenant Bingaman to report to General David B. Morgan. A number of fugitives joined him here. While calmly waiting, determined there to check the enemy or to die, Colonel Thornton, who had been driving our disorganized forces before him, suddenly fell back. He had just been apprised of the disasters on the other side and ordered to recross the river.” (Claiborne’s Mississippi.) This company of volunteers returned to Natchez February 14.

Children of Katherine and James. I’m curious why information on these children of a prominent family has been so hard to find. Maybe they didn’t have offspring themselves.

i Frances Chotard Wilkins was born on 25 Dec 1823; d. 6 Oct 1853; m. 12 Oct 1836 Lowndes, Mississippi to Robert Lindsey Ellis (b. 1820 Lowndes County, MS) Frances and Robert had one daughter Isabella J Ellis (1842 – 1917)

ii. Charles Minor Wilkins b. 2 May 1825; d. 14 Aug 1835.

iii. Rachel Rebecca Wilkins b. 27 Aug 1827; d. 25 Apr 1876

In the 1870 census, Rebecca and her sister Louisa were living with the widow J C. Roleswart in New Orleans Ward 4, Orleans, Louisiana

iv. Louisa Wilkins b. ~1830 Mississippi; d. 27 Feb 1910.

In the 1880 census, Louisa was living with her sister widow Catherine Boyd (b. 1813 Mississppi in Natchez, Adams, Mississippi. Also in the household included:

- Catherine Boyd (67) Louisa’s half-sister

- Errol Boyd (34) Catherine’s son

- Saml S. Boyd (32) Catherine’s son

- Ann Boyd (21) Catherine’s daughter

- Louisa Wilkins (50) sister

- W. H. Wilkins (40) brother Deputy Assessor

- Julia Wilkins (32) Black, Servant

- Margaret Wilkins (13) Black, daughter

- Georgiana Wilkins (11) Black, daughter

- Julia Wilkins (8) Black, daughter

- Louisa Wilkins (6) Black, daughter

- Thomas Wilkins (1) Black, son

- Jane Brevington (67) Black, mother

v. Stephen Minor Wilkins b. 28 Jul 1835 Mississippi; d. 25 Nov 1871.

A Stephen Wilkins serviced in Company F, Missouri 10th Infantry Regiment of the Union Army.

In the 1870 census, Stephen may have been living in Natchez without occupation.

- S T Wilkins (34)

- Ella Wilkins (24) 2nd Wife?

- R E Wilkins 11 (male)

- Andrew Wilkins 1 (male)

Strangely, there was another family in 1870 Natchez with almost the same information

- Henry J. Wilkins (34) Printer

- Ella Wilkins (24)

- Roberta L. Wilkins (4)

- Andrew G. Wilkins (1)

vi. W H Wilkens b. 1840 Mississippi; Deputy Assessor in Natchez, Mississippi in 1880 census.

Wilkins, W.H.(Tip) Washington artillery.

Wilkins, H.J. Lieut. Co. 48th Miss. Regt..

5. Stephen Minor

Stephen’s wife Charlotte Walker was born about 1805 in Greene Co., Pennsylvania.

6. William John Minor

Upon the death of his father Stephen in 1815, his uncle Col. John Minor (See William MINER‘s page) managed the family affairs until William J. Minor became of age. (21 in 1829)

William’s wife Rebecca Ann Gustine was born 17 May 1813 in Carlisle, Cumberland, Pennsylvania. Her parents were James Parker Gustine (1781 – 1818) and Mary Ann Duncan Gustine (1790 – 1863). She was the niece of wealthy Natchez planter and investor Stephen Duncan. Rebecca Ann Gustine’s sisters, Margaret and Matilda, were married to brothers Charles and Henry Leverich, who were successful cotton factors and commission merchants in New York and New Orleans. Rebecca Ann died 14 Jul 1887 in Cayuga Lake, New York.

William John Minor was educated by private tutors until he entered the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia in the 1820s. There, he became acquainted with Rebecca Ann Gustine. William John Minor and Rebecca Ann Gustine were married in Philadelphia on July 7, 1829.They returned to Natchez in the 1830s, living at Concord. The Minors had eight children: Duncan, Francis, Henry, James, John, Katherine, Stephen, and William.

He was the second president of the Agricultural Bank at Natchez, and much of his early correspondence deals with the bank’s affairs.

About 1828, Minor acquired land in Terrebonne Parish. From 1839 to 1842, he was in dispute with the U. S. Treasury Department because of a debt the bank owed. He was one of the wealthiest planters of the Natchez area and owner of at least three plantations in Louisiana (Southdown, Hollywood and Waterloo) in addition to Concord Plantation, the family home

Although his homestead was in Adams county, Miss., he opened up land in Terre Bonne parish, La., as early as 1828, and soon became the owner of large tracts in that, Ascension and Concordia parishes. In 1864 he came to Terre Bonne parish and settled on the property now known as Southdown.

Mr. Minor was deeply interested in education and religious matters and was a strict member of the Episcopal church.

As a hedge against declining cotton prices, Minor sought to diversify his holdings by investing in sugar-cane production in Louisiana. He acquired Hollywood Plantation (1,400 acres) and Southdown Plantation (6,000 acres) in Terrebonne Parish and Waterloo Plantation (1,900 acres) in Ascension Parish. Prior to the Civil War, these three plantations were producing an average of more than twelve hundred hogsheads of sugar annually. Although Minor was largely an absentee owner, entrusting the management of his plantations and slaves in Louisiana to overseers, he was meticulous in the administration of his holdings. His net worth, including hundreds of slaves, was estimated to be more than one million dollars in 1860. Minor also found time to serve as a captain in the Natchez Hussars, a local militia unit, and as president of the Agricultural Bank in Natchez.

Nationally recognized in the breeding and racing of horses, William John Minor owned at least sixty thoroughbreds during his lifetime. Under the pseudonym, “A Young Turfman,” Minor authored more than seventy articles on horse racing for the Spirit of the Times, a New York sporting-life newspaper, between 1837 and 1860. The paper aimed for an upper-class readership made up largely of sportsmen.

Under the pseudonym, “A Young Turfman,” William John Minor authored more than seventy articles on horse racing

The Spirit relied on amateur correspondents to cover sporting events across the United States. By the end of the 1830s, these writers had begun to submit fiction as well, including horse-racing fiction, hunting fiction, and tall tales. The paper thus served as an early outlet for many American authors. Among the Spirit’s correspondents who would go on to literary careers were George Washington Harris (who used the pseudonyms ‘Sugartail’ and ‘Mr. Free’), Johnson Jones Hooper,Henry Clay Lewis, Alexander McNutt, and Thomas Bangs Thorpe. Many contributed anonymously, as writing was not always seen as a respectable profession.

As these humor segments grew more popular, Porter sought out new writers. Among the humorists he published were Joseph Glover Baldwin, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, and William Tappan Thompson. Many of these writers concentrated on Southwestern humor, that is, humor relating to Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee.

Minor also published a pamphlet entitled Short Rules for Training Two Year Olds, which was published by The Picayune in New Orleans in 1854. Minor was also instrumental in founding local cricket and jockey clubs in Natchez.

William J. Minor, who managed the plantation business, was very well known for his high living and lavish entertaining. He liked racing and built large stables for the fine horses he purchased for the sport of kings. Minor and his nephew, Duncan Kenner , of Ashland Plantation, each had a private track for training purposes and took many honors on the turf, racing their fine horses at Baton Rouge, New Orleans, Natchez, and Mobile.

In 1846-47. Minor’s race horse winnings totaled $4,225. Among the horses from his stables winning races in these two years were: “Warwick,” “Verifier,” “Jenny Lind,” “Black Deck,” and “S. Maggie.” The horse named “Verifier” was kept in Baton Rouge in 1850-51. All these horses were raced at Baton Rouge, New Orleans and Natchez. They and others belonging to W. J. Minor (“Post Oak”, sold in 1840; “Britannia”, referred to in 1842; and “Lecompte,” raced in 1855) undoubtedly raced at Mobile, Alabama, also. During the years from 1848 through 1852, Minor employed Thomas Alderson as horse trainer. The costly stables built in 1858 burned in 1861, but were re-built sometime after the Civil War

Active in Whig politics in the years before the Civil War, William John Minor lobbied against secession throughout the South. He was convinced that secession and war would lead to economic ruin for the planter class. Capt. Minor wrote the governors of all the southern states, before the articles of secession were voted on, and used his influence to prevent their passage.

When war did come, Minor remained loyal to the Union despite the social ostracism and economic losses that his family would suffer during and after the war. General Benjamin Franklin Butler at New Orleans consulted him frequently, but William Minor refused a commission to visit President Lincoln and discuss the state of affairs in the occupied portions of Mississippi and Louisiana, fearing it would bring further damage to his family.

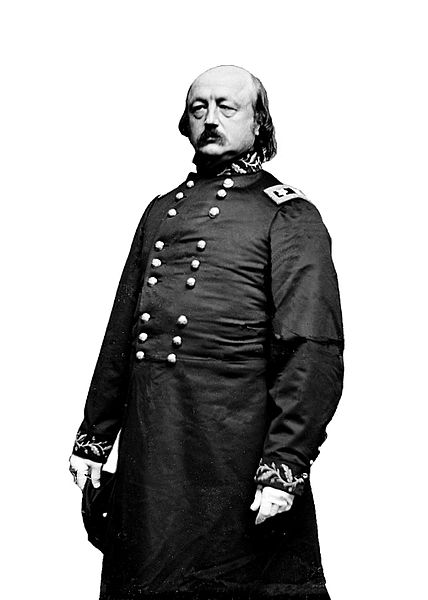

Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Butler (1818 – 1893), later Governor of Massachusetts would frequently confirm with William John Minor when he was General in occupied New Orleans

Maj. Gen. Franklin Butler showed great firmness and political subtlety in the administration of New Orleans. He devised a plan for poor relief, imposed strict quarantines and introduced a rigid program of garbage disposal to stem the spread of Yellow Fever, demanded oaths of allegiance from anyone who sought any privilege from government, and confiscated weapons.

Many of his acts, however, gave great offense. Most notorious was Butler’s General Order No. 28 of May 15, 1862, that if any woman should insult or show contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States, she shall be regarded and shall be held liable to be treated as a “woman of the town plying her avocation”, i.e., a prostitute. This was in response to women in the town who were pouring buckets of their own urine on Union soldiers, and who at the time could get away with anything as respectable women. Butler’s order had no sexual connotation; rather, it permitted soldiers to not treat women performing such acts as ladies. If a woman punched a soldier, he could punch her back.

The order stopped all of their behavior, without arresting anyone or firing a bullet, but provoked protests both in the North and the South, and also abroad, particularly in England and France. He was nicknamed “‘Beast’ Butler” or alternatively “‘Spoons’ Butler,” the latter nickname derived for his alleged habit of pilfering the silverware of Southern homes in which he stayed. While no proof exists that Butler was corrupt it is possible that he knew of the illegal activities of his brother Andrew, also in the army in New Orleans.

On June 7 Butler executed William B. Mumford, who had torn down a United States flag placed by Admiral Farragut on the United States Mint in New Orleans. Most, including Mumford and his family, expected Butler to pardon him; the general refused, but promised to care for his family if necessary. (After the war Butler fulfilled his promise, paying off a mortgage on Mumford’s widow’s house and helping her find government employment.) For the execution and General Order No. 28 he was denounced (December 1862) by Confederate President Jefferson Davis in General Order 111 as a felon deserving capital punishment, who if captured should be reserved for execution.

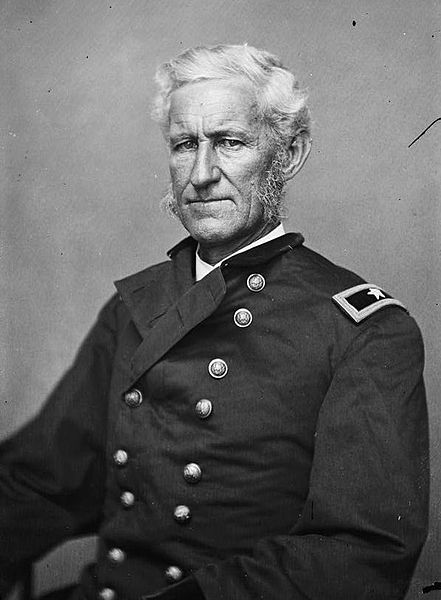

William’s wife Rebecca was a Philadelphian, and she too, was a staunch Unionist. Union officers protected Concord Plantation on two separate occasions, Sep 29, 1863 and Mar 10, 1864. William moved to Southdown in Terrebonne Parish in 1864. In May 1864 Adjutant General of the United States, Lorenzo Thomas gave Rebecca Minor a pass allowing her to pass with her servants and baggage to any point in the North without molestation or hinderance, and in a like manner to return, when so disposed to any parts of the Southern states within the lines of the U.S. Army.” It was the type of pass, unlimited in time and place, that only known Unionists could obtain.

U.S. Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas (1804-1875) gave Rebecca Minor an unlimited travel pass in May 1864.

Although the majority of William John Minor’s sons remained loyal to the Union, one son was conscripted and another enlisted under public pressure in the Confederate army against his father’s wishes.

During and after the Civil War, W. J. Minor’s problems were felt most acutely because his properties were in three separate locations in Louisiana and in one in Mississippi, and because he and his wife strongly opposed the war. Politically, Minor was a Whig. His 1859 Diary (entry for January 22,) reveals that he owned 399 slaves: 176 at Southdown, 165 at Waterloo, and 58 at Hollywood. His wife was opposed to slavery, but often remarked that she did not know how to resolve the economic and social problems which were an inevitable part of emancipation

William John Minor died in Terrebonne Parish on September 18, 1869. Rebecca Ann Gustine Minor died in Cayuga Lake, New York, on July 14, 1887.

Southdown Plantation

Southdown located in Houma, Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, approximately 60 miles southwest of New Orleans, was built on part of a Spanish land grant to Jose Llano and Miguel Saturino, who were engaged in growing indigo. In 1790 and 1798 respectively, two more tracts were given to them by Charles IV, King of Spain.

In the 1920’s Southdown’s sugarcane played a dramatic role in rescuing the Louisiana sugar industry. Mosaic disease was causing severe crop losses. A heartier subspecies of sugarcane was developed, grown on the fields of Southdown, and distributed to the rest Louisiana’s sugarcane planters.

Subsequently, the property was owned by the noted adventurer and soldier, Jim Bowie , renowned for the knife named after him and for his exploits at the Alamo.

In 1828, William John Minor purchased the plantation. In 1858, he built the house with brick made in his own kilns and with cypress from his own swamps. It is now the Southdown Museum and home to the Terrebonne Historical & Cultural Society.

Each fall, Southdown Plantation hosts the Voice of the Wetlands Festival, showcasing dozens upon dozens of world class musical artists kicking off the weekend on a serious musical note in the traditional “Friday Night Guitar Fights” with performances from the likes of Joe Bonamassa, Tab Benoit, Sonny Landredth, Paul Barrere, Camille Baudoin, Mike Zito and Joe Stark. Continuing through the weekend, we have listened to the extraordinary sounds of Dr. John, Beausoliel, The Radiators, Susan Cowsill, The Producers, Zebra, Amanda Shaw, Chubby Carrier and especially Louisiana LaRoux, whose appearances at the Festival have become a true South Louisiana must see tradition. And completing the perfect weekend, a performance by the acclaimed Voice of the Wetlands All Stars, recognized by rave reviews and sold out performances across the nation as a truly talented cultural and blues musical ensemble.

Southdown appears very different in design from the homes normally seen on plantations of the Old South. Gothic Revival architecture was slightly less popular than Greek Revival at that time, but the Minors nevertheless chose the former. Instead of the familiar white columns, Minor erected a smallish, simple entrance gallery. The original house, begun in 1858 and completed in 1862, consisted of what is now Southdown’s main floor, which includes the twin front turrets and the rear center turret. The top floor and the turrets were added in 1893 by William’s son, Henry C. Minor.

This brick home has twenty rooms; the brick and plaster walls range between twelve and twenty inches of thickness. The center hall doorways are flanked by beautiful stained glass in a sugarcane design. Second-floor side galleries face up and down Little Bayou Black, and a balcony opens from the rear. Just behind Southdown stands a two-story brick structure that served as a kitchen for the manor and as a home for the house servants – a two story slave dwelling is an unusual sight in Louisiana outside of the Vieux Carre. A covered walkway once connected this building with the “big house”.

The first floor of the present Southdown house was built between 1858 and 1862 of brick made in the brick kiln constructed at Southdown in 1858. William Minor, Jr., to W. J. Minor, April 13, 1860, wrote his father: “We will have by Saturday night two 100 thousand brick (sic) made so you see that we are making youse (sic) of the dry weather. The tower (bagasse tower) is getting on but slow. Mr. D (J.B. Dunn, the brick mason) has to (sic) many irons in the fire.” In her narrative, “The Federal Raid Upon Ashland Plantation in July 1862,” Rosella Kenner Brent, the daughter of Duncan Kenner who was first cousin to W. J. Minor, states that in the Kenner family’s flight from the Union troops in early August, 1862: “…when we reached the town of Houma, we were met by William Minor, Jr., who was then living on Southdown Plantation. He took us to his house which was newly built, large & comfortable & gave us a hearty & cousinly welcome.”

The timber used in the construction of Southdown is cypress. It was cut from the native cypress which grows on Southdown property. The mill work on the wood used in building the first floor was in all probability done by Charles Minty, who was employed as carpenter and overseer at Southdown from December, 1846, into the year 1866, and/or Andrew Douglas, the carpenter who operated the sawmill which W. J. Minor had built at Southdown in 1857

The first crop grown at Southdown was indigo but various factors made sugarcane more rewarding.

What sparked the switch from indigo to sugar cane was the market demand for sugar and acceptance, of the domesticated purple and blue striped “ribbon” cane introduced from Java about 1820. This very hardy variety of cane replaced the old “Malabar” or “Creole”, variety introduced from Santo Domingo in 1751 (or 1733?) and the “Tahiti” variety introduced in 1797. The growth of sugar cane in south Louisiana was further encouraged after 1830 by the introduction of steam driven mills and by improvements in the manufacture of granulated sugar made commercially feasible by Etienne de Bore’ in 1795

Southdown was named after a variety of English sheep, Southdowns, that the Minor family imported to eat the weeds and grass between the rows of sugarcane.

Despite the great contribution that Southdown owners had made to the sugar industry, they could not weather the many setbacks that occurred during the early 1920’s. During the economic crash of October, 1929, and the severe Depression of the 1930’s, all their property was lost to the creditors.

Sadly, the family legacy of Southdown House, where so many notables were entertained at gala affairs, was ended when a new owner took possession in 1932. For more than four decades, the home was utilized by the new owners to house various plantation personnel.

Southdown House gradually fell into a state of disrepair, but the Terrebonne Historical and Cultural Society, Inc. had the foresight to start a movement to save the great mansion. On July 31, 1975, that dream was realized when the owners donated the home, servant quarters, and four and a half acres of land to the society for the purpose of historical preservation, cultural activities, and a museum of arts and crafts of Terrebonne Parish.

Children of William John and Rebecca Ann:

i. John Duncan Minor b. 8 Aug 1831 Concordia, Natchez, Adams, Mississippi; d. 26 Jun 1869 New York City. Interred at Oakland Plantation. He was later reinterred in the Natchez City Cemetery; m. 6 Mar 1855 at Cherry Grove, her father’s plantation to Katherine “Kate” Surget (b. 27 Apr 1834 in Natchez, Adams, Mississippi – d. 17 Feb 1926) Kate first married John Duncan’s brother James Gustin and divorced. Kate’s parents were James Surget Sr. and [__?__] John and Kate had five children born between 1855 and 1868. James Surget (1855-1864); Mary Grace (1858-ca. 1859); Katherine Surget (b. 1860); Duncan Gustine (b. 1862); and Jeanne Marie (b. 1868).

John was privately educated by private tutors until he entered the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) in 1848. Although frequently ill at school, Minor completed his education and returned to Natchez in the early 1850s. He soon became involved in local equestrian life, including fox hunting and high-stakes racehorse gambling, and attending rounds of social gatherings such as dinner parties and fancy-dress balls. Minor also began a courtship with Kate Surget, . They were married at Surget’s plantation, Cherry Grove, on March 6, 1855.

Following a severe bout of yellow fever, James Surget, Sr., died intestate on August 27, 1855. His children, James Surget, Jr., and Kate Surget Minor, divided the elder Surget’s estate, which was estimated at around three million dollars. Kate Surget Minor’s inheritance included Carthage Plantation (2,095 acres) in Adams County and Palo Alto Plantation (2,560 acres) in Concordia Parish, as well as hundreds of slaves and considerable agricultural stores and livestock.

At the time of John Minor’s marriage to Kate Surget Minor, his father gave him $10,000 for the purchase of Oakland, an estate near Natchez. His wife supplied an additional $5,000 to complete the purchase of this property in 1857.

Today, Oakland Plantation is a hotel at 1124 Lower, Woodville Rd. Natchez, MS. They say ~1785. Andrew Jackson courted his future wife, Rachel Robards, at this gracious 18th-century home. The guest rooms are located in the old servants’ quarters building, just steps from the main house. This working cattle plantation includes fishing ponds, a tennis court and canoeing. Rooms are filled with antiques, and the innkeepers provide guests with a tour of the main home and plantation. They also will arrange tours of Natchez.

Kate Surget Minor also acquired Wannacutt Plantation (1,217 acres) in Concordia Parish in 1857. The deed to this plantation was recorded in the name of John Minor, and the income from it was apparently intended for his personal use. John Minor acquired no additional real property with his own funds during the course of his fourteen-year marriage to Kate Surget Minor.

Although the Minors shared the burden of plantation management during the early years of their marriage, it became increasingly necessary for Kate Surget Minor to shoulder more of this responsibility on the eve of the Civil War. In her role as plantation mistress, Kate Surget Minor was also responsible for supervising many aspects of domestic life at Oakland and on the working plantations.

As the threat of secession and war became imminent, John Minor enlisted as a first lieutenant in the Adams Troop, a local cavalry company organized by attorney William T. Martin in 1860. Its recruits were mainly from wealthy families in Adams County. The cavalry company was intended to counter potential lawlessness in the county. However, when Mississippi ratified the Confederate constitution in March of 1861, the Adams Troop also began to prepare for war. When war came in April of 1861, John Minor resigned his commission and publicly declared his support for the Union.

Fearing forced conscription in the Confederate army, John Minor eventually paid a man $5,000 to serve in his place. His decision to support the Union cause would also have social and economic consequences that would adversely affect his family during and after the war. Many of Minor’s friends and acquaintances considered his behavior to be dishonorable and therefore openly censured him. His wife was also spurned by many of her friends and acquaintances, including her best friend, Margaret Conner Martin. The Minors further alienated themselves by entertaining Union officers at Oakland after Natchez was occupied in July of 1863.

The Unionist sympathies of the Minors initially made them more vulnerable to the expropriation of cotton, horses, livestock, stores, and supplies on their Louisiana and Mississippi plantations by Confederate officers. However, their Unionist position would not shield them from later expropriations by Union officers, which were far more severe in terms of economic loss. Emancipated slaves and itinerant whites later plundered what the Confederate and Union armies failed to take.

The Minors survived the Civil War with their plantation holdings essentially intact. They soon applied for pardons from President Andrew Johnson in 1865, since amnesty ensured that they would have full control over the management of their plantations. The Minors gradually adjusted to a wage-based labor system supervised by the Freedmen’s Bureau, which approved labor contracts between planters and black workers. It was necessary to mortgage Carthage and Palo Alto plantations in order to raise sufficient capital to rebuild, make necessary repairs, pay wages, and harvest a marketable cotton crop. It was also necessary to sell the heavily mortgaged Wannacutt Plantation to the Louisiana State Bank. Declining cotton prices, family illness, flooding, insect damage, labor problems, and yellow-fever epidemics often confounded the Minors’ attempts to produce a successful cotton crop during Reconstruction.

The health of John Minor worsened in the late spring of 1869. Hoping to recover, he traveled to New York for the summer. However, a short time after arriving at his New York hotel, he sustained a serious head injury in a fall. Minor died the following day on June 26, 1869. Survived by his wife, Kate, and three young children, Katherine Surget, Duncan Gustine, and Jeanne Marie, John Minor was interred at Oakland. He was later reinterred in the Natchez City Cemetery.

The finances of Kate Surget Minor began to improve toward the end of Reconstruction. After the 1869 death of wealthy uncle Jacob Surget, she inherited several plantations jointly with her brother, James Surget, Jr., and $26,000 in securities. Kate Surget Minor and her brother also formed a partnership to administer their properties, which lasted until the death of James Surget, Jr., on May 1, 1920. During the post-war years, revenue from her plantation holdings was primarily generated from annual leasing or sharecropping agreements with tenants. Initially, James Surget, Jr., assisted her in the management of the jointly held plantations, but in later years her son, Duncan Gustine Minor, would assume full responsibility for the management of her properties.

Kate Surget Minor filed a petition with the Southern Claims Commission in the summer of 1871. The mandate of this commission, which was created by Congress in March of 1871, was to determine the validity of monetary claims of loyal southern Unionists whose property had been confiscated by the Union army during the Civil War. Her claim for losses on Carthage and Palo Alto plantations totaled $64,155. However, after nearly a decade of litigation, the commission disallowed the majority of her claim and awarded only $13,072.

Kate Surget Minor had regained much of her former wealth and status by the 1880s. At the time of her death on February 17, 1926, she owned the estate, Oakland; Blackburn, Carthage, Magnolia Place, and Palo Alto plantations; and a half-interest in Brighton Woods, Cole Hill, Fatherland, Hunters Hall, Hurricane, Jane Surget White, and Mount Hope plantations, which were jointly held with her brother, James Surget, Jr. Kate Surget Minor died intestate, and her estate was equally divided among her three surviving children. Duncan Gustine Minor served as administrator of the estate. However, litigation among the three heirs delayed the final settlement of the estate until 1941.

Katherine (Tassie) Surget Minor married Frederick Schuchardt, a grandson of the Leveriches, at a lavish wedding and reception at Oakland in 1882. The Schuchardts had three children: Frederick, Jr., Katherine, and Mary Ann, and they lived in New York. Frederick Schuchardt, Sr., died in 1894, and Katherine Surget Minor Schuchardt died in 1934.